Art and Culture

Saints & Sinners: A Dialogue on the Hardest Topic in Science

We harbor no illusions that a single article will alter anyone’s mindset on the issue of race differences in a deeply appreciable manner.

“Some rise by sin, and some by virtue fall”

– Escalus; in ‘Measure for Measure’ by William Shakespeare

There is arguably no topic more incendiary (about which scholars say less, ironically) than race differences in general, and in particular, race differences in behavior and achievement. There are certain subjects that are so politically charged and fraught with consequences that any scientific research on the topic is instantly applauded or demonized (depending on your viewpoints), no matter the findings. The subject of race differences, broadly defined, falls squarely in this category. For the purposes of this discussion, and because we are behavioral scientists, we focus on the issue of race differences in behavior.

In our experience, the perception seems to be that two camps exist for the study of race differences in behavior. In the first camp, race is seen as a social construction, one that, if it is consequential, is so because of the way people react to individuals on the basis of race. Any race or ethnicity differences that emerge — for behavior, intelligence, occupational achievement, health and wellbeing, and so on — is largely attributable to unequal treatment or systemic bias. Any argument that the differences are not due to inequality is met with instant skepticism. We think it’s reasonable to argue that many, if not most, members of the academy (particularly in our fields of sociology and criminology) represent this latter view.

On the other side (camp 2), a growing tide of researchers, under the biosocial umbrella, are arguing that discrimination cannot fully account for racial differences in attitudes, intelligence, behaviors, and other outcomes (and may, in fact, not matter that much, in comparison to other relevant factors that also differ across racial categories).

These two camps do not talk much; when they do engage, it seems to generally devolve into hostilities aimed at one another. “Social construction” is a vacuous term to many biosocial researchers, as it represents fictionalized, PC-fantasy worlds. For the other side, talk of anything other than a social construction to race smacks of biological racism, and Nazi atrocities of the past. These disagreements have stunted the study of race in the social sciences in two ways.

First, as mentioned, these two camps do not share ideas or civil discourse. They publish in different journals. They generally do not read one another’s work. They have a tendency to dismiss social construction/discrimination hypotheses or biosocial conceptions of race differences, out of hand. Second (and far more insidious than the first point) is that they vilify each other’s work. Some researchers are seen as promoting social justice at the expense of scientific objectivity. Or they are seen as promoting a racial hierarchy by trotting out results that will lead inexorably to social harms. Owing to these two issues, research on race differences in the social sciences hasn’t progressed as it could. More broadly, discussions about race and behavior are stunted in our society at large. People are afraid, afraid of what they may be called. Afraid of how their work may be misinterpreted by others, and afraid of falling prey to the swift and certain justice of shaming on social media sites. In addition, what could be seen as common ground between the camps instead is used as battle lines.

Our goal in this article is simply to promote a more civil discourse about race differences and behavior. Our approach is unique: one of us is a sociologist (or sociological criminologist), trained as a sociologist and in traditional criminology. The other of us is a biosocial criminologist, trained across a range of biologically informed disciplines. Clearly we come to the study of race and behavior from different vantage points—and yet we see the importance of sharing our insights, of listening to the other, and of figuring out where we can move the fields in a positive direction. What follows is a dialogue representing the sociological (Mike’s) perspective and biosocial (Brian’s) perspective. We conclude with some reactions and a way forward.

Sociological views on race differences

Mike: I am a sociologist or a sociological criminologist by training. This does not mean that I view society as a fantasy world, constructed out of thin air, ready to collapse at any minute. In fact, that is the extreme version of “social constructionism” which builds a straw man out of the field. What social constructionism seeks to highlight, rather, is that social interactions, interpretations, and labels, all do matter. They matter a great deal with respect to how we are treated by others (teachers, for instance). They matter with respect to how we feel about ourselves, and subsequently, how we behave.

Sociologists, in addition, often see social justice as an important part of their research agenda. The textbook I use to teach Sociology 101 at Bates College is called Sociology: Understanding and changing the social world. It’s part of the field. And so we are necessarily drawn to studying discrimination, injustice, inequalities. This is the lens through which we see racial issues. We see stark disparities in things like arrest rates, school suspensions, school achievement, and healthcare, and wonder why.

It’s natural then, when conducting our research, to draw on the literature sociologists create and are exposed to regarding bias and discrimination. We are well versed in the General Social Survey, which is a nationally representative survey conducted since 1972 on US citizen’s attitudes. We see that racial bias does exist and it is real. Perhaps this has some role in causing the disparities we see in the literature. It’s our natural inclination to look. And that explains why we (myself included) are more likely to look in certain places rather than others for the source of the disparities.

Is race “real?” This is another point of contention between biological social scientists and sociologists. Some argue, in fact, that there is absolutely no real biological basis to race itself. Many sociologists, however, would not deny that biology has something to do with race. To the extent that racial characteristics such as skin tone and hair style are passed down inter-generationally, that of course must be true. The rub comes in using whatever genetic component there is for race to explain behaviors or achievement. When sociologists talk about race being socially constructed, we do not mean it is artificial — we mean that what is considered markers of race are socially constructed. Skin tone, eye shape, and hair texture are considered biological markers of race. But they were selected by humans as such. Why not hair color? Why not eye color? But should we expect that the genetic components which determine hair texture, or with having either blonde or brunette hair, have much of anything to do with behavioral differences?

In the end, I think the distinction sociologists have made with respect to gender (social) and sex (biological) would be useful for race. Race, like gender/sex, has both social and biological components. There may be much ground to be covered by attending to both rather than conflating them.

Biosocial views on race differences

Brian: Mike and I disagree for a host of reasons on the issue of race. Moreover, we disagree about the role that things like social justice movements (however you define that) should play in our field. Nonetheless, I’m continually gratified to know that these disagreements — some of which I will outline here — have never impeded our friendship. It is possible to disagree with someone and still value them.

Is there a social aspect to the construction of race? Yes, of course there is. To assume that historical and cultural factors play no role in how we think about, and react to, issues surrounding race and ethnicity is naïve (and wrong). Is there any biological component to race? Yes, there is. We can see it emerge as data and findings continue to amass in the field of population genetics. As my colleagues and I noted:

Race, then, is not a platonic essence and racial groups are not discrete categories of humans. Instead, race is a pragmatic construct that picks out real variation in the world (which corresponds to shared ancestry) and allows people and scientists to make useful inferences.

I’ve had to resist the urge to delve more deeply into this issue in light of space considerations, yet I would direct you to a helpful overview. Needless to say, it seems racial classifications capture something beyond just skin tone and hair texture (or historical and cultural attitudes and beliefs).

Now, arguing that we can trace ancestral heritage at the genetic level does not mean that these genetic differences are certifiably responsible for differences we observe in traits like general intelligence, general health, violence, or other key variables that social scientists are interested in. Allow me to table that issue, though, so that I can highlight another point of contention with Mike as it relates to the issue of discrimination. The issue is not whether discrimination exists. Rather, the real point on which I wish to press Mike’s camp is whether other variables might play a larger role in explaining the existence of race differences.

For example, using a national data set of American respondent’s, we uncovered evidence that differences in self-reported arrest rates between Blacks and Whites evaporated completely when you accounted for differences in levels of intelligence and prior violent behavior across groups. I would never suggest that we should stop with one study, our results are in need of replication, and they might in fact not replicate in other samples. Even so, meaningful race differences exist for key traits like personality constructs, violent behavior, impulsive behavior, and general intelligence (see Barnes et al., 2016 for a recent treatment of the topic). Why not account for that empirically?

To suggest that these race differences in traits might matter, though, offends many of our colleagues desperately — some of whom persist in bizarre notions that traits like general intelligence don’t even exist, or that it doesn’t capture anything meaningful, or that the instruments used to probe its existence are biased; as well as several other popular misconceptions. Proposing that we should account for race differences in these relevant traits when examining differences in behavioral outcomes is often met with baffled stares; bald incredulity that someone could suggest something so barbaric and distasteful. Returning quickly to the issue of the role that genetic differences between groups might play in creating the differences we observe for violence, cognitive ability, executive functioning, so on and so forth.

As folks before me have noted, there are three possibilities: genes explain all of the difference, they explain none of the difference, or genetic differences account for some of the differences, in some (but not all) traits. The answer to that question is not up for political grabs. It is empirical, subject to scientific inquiry, quantifiable, and in short, answerable. Researchers in the first camp need to stop punishing us for trying to answer something that is an answerable question. That is our job.

I’ll end with a short note about “social justice.” It is a deeply lamentable term, because it means nothing. It could have meant something, and likely did mean something at some point, but recently is seems to have been co-opted, now used to refer to anything politically correct and to identify the “righteous” among us. There is a disconcerting push, moreover, to drag it into science. You must either seek social justice, or reside among the unclean masses. Being a biosocial scholar of race differences has been twisted to represent the inverse of social justice. The biological underpinnings of race differences will exist or not, though, regardless of how the prevailing political winds are blowing. It is every bit as reasonable to explore the role that biology plays in creating those differences as it is to explore the possibility that social biases entirely explain those differences. The demonization has to stop.

Responses

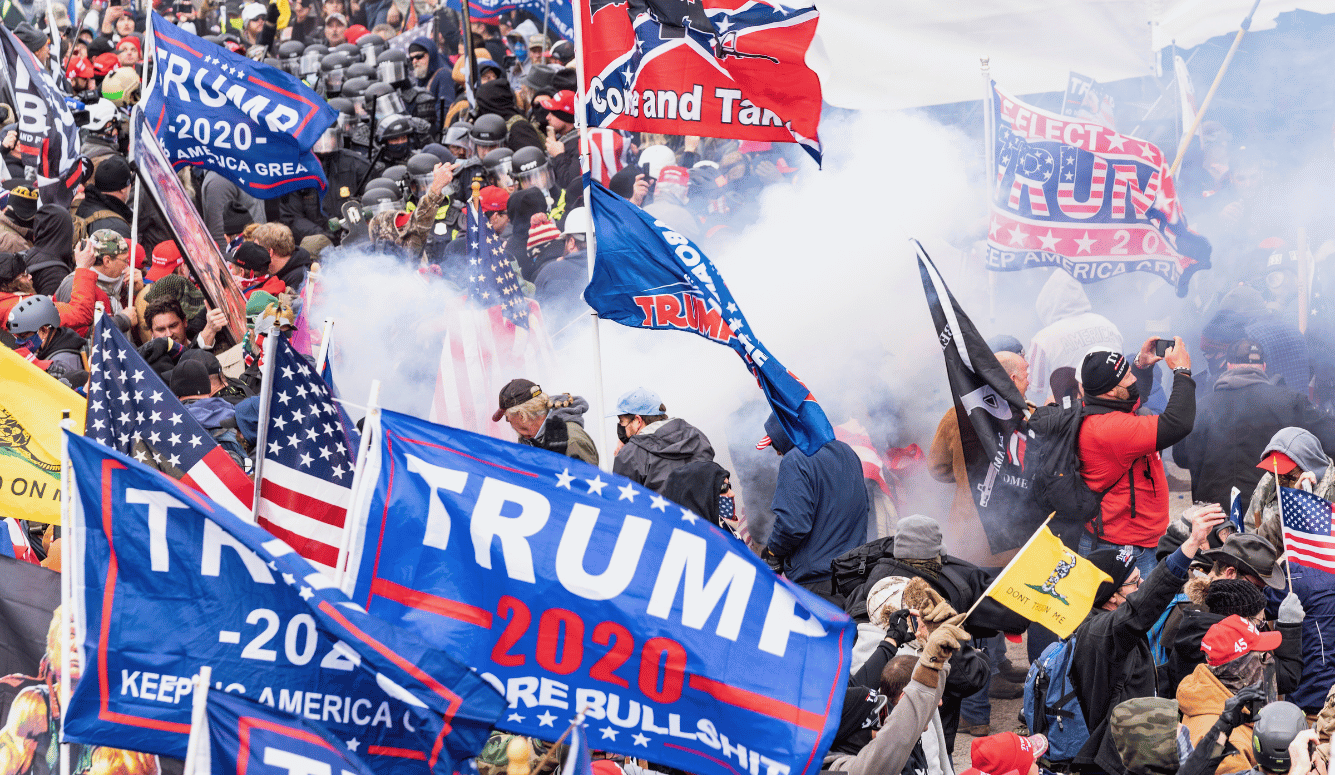

Mike: Unfortunately for those hoping for a rip roaring, no holds-barred fight, Brian and I agree on much. Disappointing, I’m sure. Sociological criminologists, for example, believe in science, data, and the importance of evidence. Brian and I also agree that science can and should help make the world a better place. Why else do we do what we do (aside from, and in addition to, pure curiosity)? We also agree, wholeheartedly, that the world is a much better place now than it was 20, 30, 70 years ago. On this score, I’m afraid Mr. Trump is mistaken when he says America must be made great again. Things are better now than they ever have been before (as Pinker also reminds us in his Better Angels of Our Nature).

But we do disagree, as you can see, on some fundamentals. First, the term social justice can be vacuous, lacking in meaning. But that’s not how sociologists view it. In simple terms, sociologists see, empirically, that there are inequalities, disparities, and biases, which fundamentally impede equal opportunity. If our research can be brought to bear on these issues, it is working toward justice. Of course some get carried away and act inappropriately, as the professor at Missouri who attempted to stifle free press illustrates. (Yet I think most sociological criminologists or sociologists would agree, there was nothing scientific or research oriented about that episode).

With respect to discrimination, it would seem our point of contention boils down to where one wishes to pursue the action. Sociologists and sociological criminologists would say that any degree of discrimination or unwarranted disparities is worthy of attention and redress. And that is the overriding concern. In addition, to the extent that behavioral differences arise, sociologists seek to find the answers in the environment. Decades of research have been accumulated on this score. We look toward studies that suggest discrimination as a non-factor as hugely important but in need of replication.

Further, and more importantly, we wonder what the end game is of research seeking to show natural race differences in things like antisocial behavior and intelligence. Is it just to shed light on “truth?” If that is the way of the world, what then? While my line of inquiry leads down the dangerous path of is vs. ought, our main contention is that there simply has not been a viable theory explaining “natural” race differences, especially given “natural” genetic categories are likely a relic of the past. Presumably, for example, all humans were shaped by evolution (which we sociologists do not deny)!

In sum, what we have here is a failure to communicate, on a large, and massive scale. Both biosocial and sociological researchers believe in the effects of the environment and individual (though to varying degrees). One burden of being a sociologist, though, is that we are always aware of the implications and potential misuse of research. Thus we wonder what will become of research that suggests race is genetic and therefore all behavioral or achievement gaps are natural. There is the danger of much damage to be done with such findings. And yet, it should be the biosocial folks who tell us what this means. And so I leave the last word to my very good friend, Brian.

Brian: As Mike noted, we (he and I) do often agree. That said it’s more valuable in this case to harp on our differences. He and I see our mandate as scientists a bit differently in some respects. To the extent that we can, we should unfailingly and unflinchingly seek the truth. I know Mike thinks this too, but his concern over the potential misuse of research is one area where we distinguish ourselves. As a thought experiment, imagine that you conducted a research project and revealed something so powerfully shocking and previously unknown that it rattled the core of human existence. Now imagine decades have passed and you discover (to your horror) that some despot has used your insight to perpetrate nearly unimaginable atrocity. Are you responsible?

Assuming you carried out your work within the ethical cannons of science, you should not be held responsible for misguided humans who are in a position to misuse your work. Consider a twist in our thought experiment,. I suspect that you had in mind (in the role of the scholar), someone studying the genetic contribution to race differences? In their stead, imagine that the person is a sociologist, whose findings definitively revealed that racial categories are a conjuring trick of our perceptions. How do you feel now about the culpability of the researcher? Their scholarship uncovered no genetic basis to race, or race differences, yet their findings still spawned evil ends. Maybe you think it couldn’t possibly play out that way? In some respects, it already has. As Steven Pinker notes in the The Blank Slate, purely malleable theories of human nature and human differences were endorsed by murderous regimes like those of Stalin and Mao. In short, if we’re going to try and cherry pick the research that we think might be dangerous, or that has the possibility for being misused; we had might as well halt all research.

I wish to make a final point. Some findings in science bring with them an unpleasant taste. That we reside, not at the center of our solar system but further out, was deeply distasteful to many when it was discovered. That humans are a product of Darwinian evolution, not the prestidigitation of an almighty creator God, remains deeply offensive to many. These facts remain unchanged, though, despite our distaste for them. Race differences exist, and they exist for the most uncomfortable of outcomes like general intelligence and criminal involvement. They exist, not because I wished for them, and they currently exist no matter how hard we might wish against them (that doesn’t mean, though, that they will always exist).

Railing against those who study them is pointless. Refusing to account for them empirically is even worse; it’s bad science. Moreover, since when do we ever let “good taste” guide the construction of a statistical model? Never. If you’re convinced that personality and intelligence differences do not matter then control for them in your research, what do you have to worry about?

The answer, in actuality, is that you have a lot to worry about. Many who agree with some part of what I have written will never say so aloud because they have careers to think about and families to provide for. Understandably, they seek to defend their reputations against the damaging punches that come from colleagues in the first camp. It’s impossible to predict all of the many ways in which studying race differences “inappropriately” can divert your career and retard its’ growth. You certainly do not expect to win awards, easily get tenured or promoted, or gain respect, by belonging to my camp. Instead, you often worry about when the next attack will come, and you wonder when it will be the last one; the one in which your university decides you’re no longer worth defending and offers you up to appease the appetites of an angry public. You dread the day when an email arrives informing you that you have come into conflict with the mission of the university and its core values. If you belong to my camp, that day is more likely to come than not.

Consilience

Using the title of E.O. Wilson’s important book seemed only fitting for this final section, because it is what we have found in our friendship and our scholarship. We have disagreements and frustrations with one another, but if we sacrifice scholarly discourse on the altar of political correctness, no one will benefit. In fact, there will only be negative consequences.

As Pinker reminded us (and as Brian alluded to earlier), blindly assuming that human nature is endlessly recast (or capable of being recast) by society can lead precisely to the very same social maladies that so-called social justice warriors are admirably looking to avoid. It is no sin to admit that society has improved. This too seems almost taboo among many liberal social scientists, acting as if any acknowledgment that people might be less prejudicial, or society less hostile to minorities and females now than in the past, is treated like some type of failure to appropriately admonish ourselves for the sins of our predecessors.

We can seek to improve as a society, and we can simultaneously acknowledge that we have indeed made very important social strides. We can study both social and biological components to race differences, acknowledging that in some cases, one side might matter more than the other, and still want all of the same principles that we hold sacred (equality for all before the law, liberty, and so on).

Aside from being important for scholarly progress, critically engaging with one another is a fun pursuit and intellectually invigorating. As Sampson and Laub noted: “complete consensus in a field of scholarly inquiry is boring, and usually indicates a lack of theoretical excitement.”

We harbor no illusions that a single article will alter anyone’s mindset on the issue of race differences in a deeply appreciable manner. Luckily, we are not evangelists, we are scientists, and the core message of our discussion is simply this: we should return to our mandate of scientists and explore all possible answers to all possible questions openly. The best way forward, we believe, is to have open, respectful conversations across all scientific aisles. Vilifying the biosocial camp, or lampooning the social construction camp, is not productive. Collectively, we hope for something better.