Identity is forged in the struggles of individuals, cultures, and civilisations to protect themselves against collapse. F. Scott Fitzgerald described this struggle in “The Crack-Up,” an essay written for Esquire in 1936. He identified two kinds of blows that lead to individual collapse: “the big, sudden blows that come, or seem to come from outside” and “another sort of blow that comes from within—that you don’t feel until it’s too late to do anything about it.” These blows aren’t equal. Those that come from outside only seem to do so. The ones that come from inside are the authentic face of the crack-up.

According to Fitzgerald, “a man can crack in many ways—can crack in the head—in which case the power of decision is taken from you by others, or in the body, when one can but submit to the white hospital world; or in the nerves.” Describing his own crack-up, Fitzgerald wrote that “after an hour of solitary pillow-hugging, I began to realise that for two years my life had been drawing on resources that I did not possess, that I had been mortgaging myself physically and spiritually up to the hilt.”

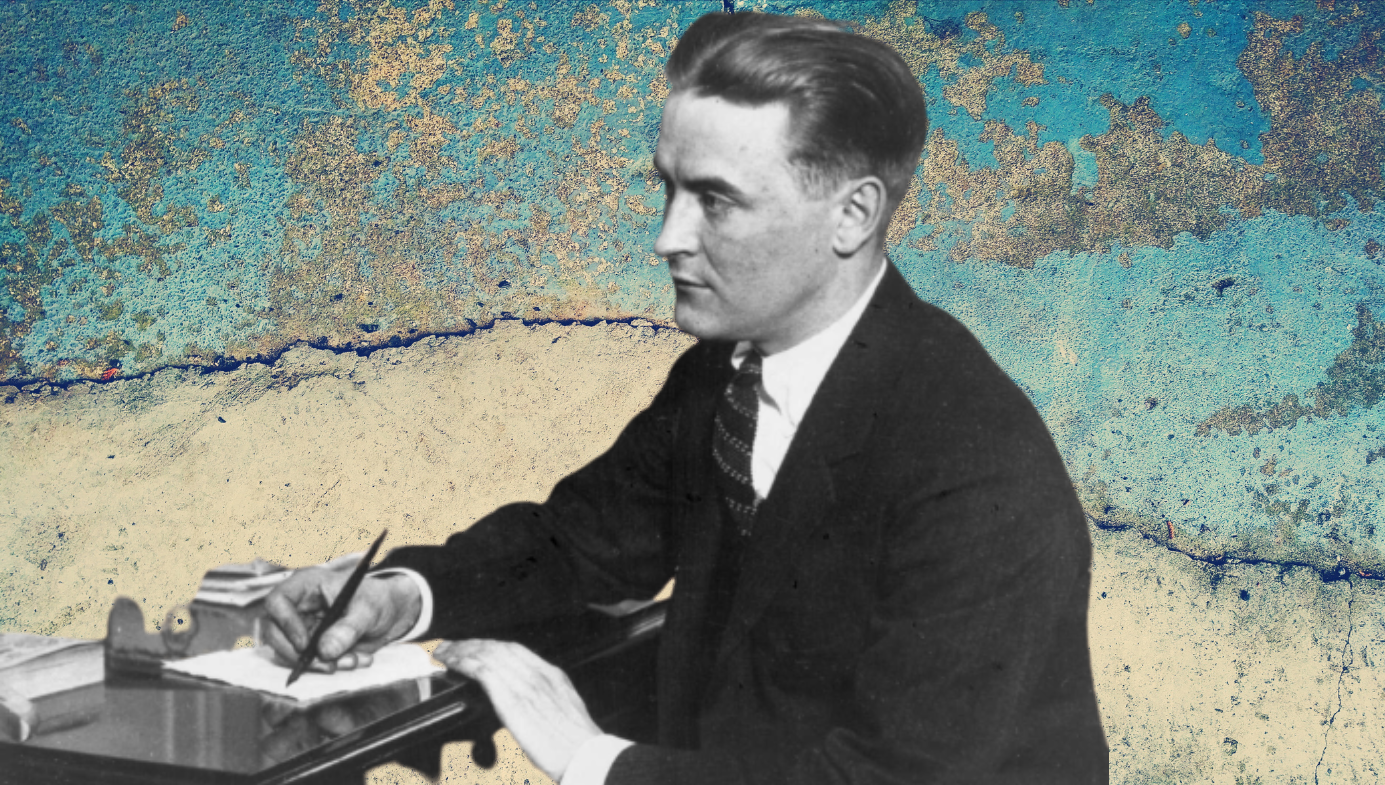

A year earlier, Fitzgerald confessed that “what I might have been … is lost, spent, dissipated, unrecapturable.” By the time he wrote “The Crack-Up” in November 1935, Fitzgerald was holed up in a hotel in North Carolina, alone and living on canned food. His life was a mess. His finances were wrecked. He owed tens of thousands of dollars and he was down to his last 40 cents in cash. His wife Zelda was in an asylum. When they let her out to accompany Scott on a walk, he had to prevent her from throwing herself under a train and she demanded to be locked up again before the moon came up. His drinking was out of control. Harold Ober, his literary agent, complained that Fitzgerald was never sober. Mrs. Guthrie, his typist and companion, noted that he drank 20 bottles of beer in an evening. His desperate hunt for cash meant the quality of his prose declined and “The Crack-Up” merely served to define him as a sick, depressed, washed-up writer.

Ernest Hemingway, who saw only shame and cowardice in Fitzgerald’s confessional essay, offered to arrange to have him killed in Cuba, leaving Zelda and their daughter, Scottie, to benefit from the insurance policy. In a letter to Fitzgerald, Hemingway promised to “write a fine obituary … and if we can still find your balls I will take them via the Ile de France to Paris and down to Antibes and have them cast into the sea off Eden Roc.”

A critic had offered Fitzgerald a less painful way out, and he describes their exchange in his essay. She suggested it might bring him comfort to believe that “this wasn’t a crack in you” and encouraged him to blame a random external cause, such as “a crack in the Grand Canyon.” Fitzgerald resisted the temptation to take the opium of accusation and absolution, and continued to insist that “the crack’s in me.” The critic refused to give up. If the world is what we make of it, then why not blame the Grand Canyon? And if such moral abdication were not sufficient, she concluded, then “by God, if I ever cracked, I’d try to make the world crack with me.” She gave Fitzgerald a choice: to own his crack-up or to abdicate responsibility and take the whole world down with him. And that’s the choice any identity—be it an individual or a civilisation—has to make.

The French poet Paul Valéry wrote that “a civilisation has the same fragility as a life” and that understanding this fragility is crucial to our individual and collective survival. Every empire, like every life, ends. Our deepest fear at the end of life isn’t the nothingness of non-existence. It’s the horror that there is life after the “end”—that the Self cracks and lives on, crushed, depressed, destitute, shattered into pieces. The same fear haunts collective collapse. Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno warned that, “as its final result, civilisation leads back to the terrors of nature”—an afterlife of unspeakable cruelty.

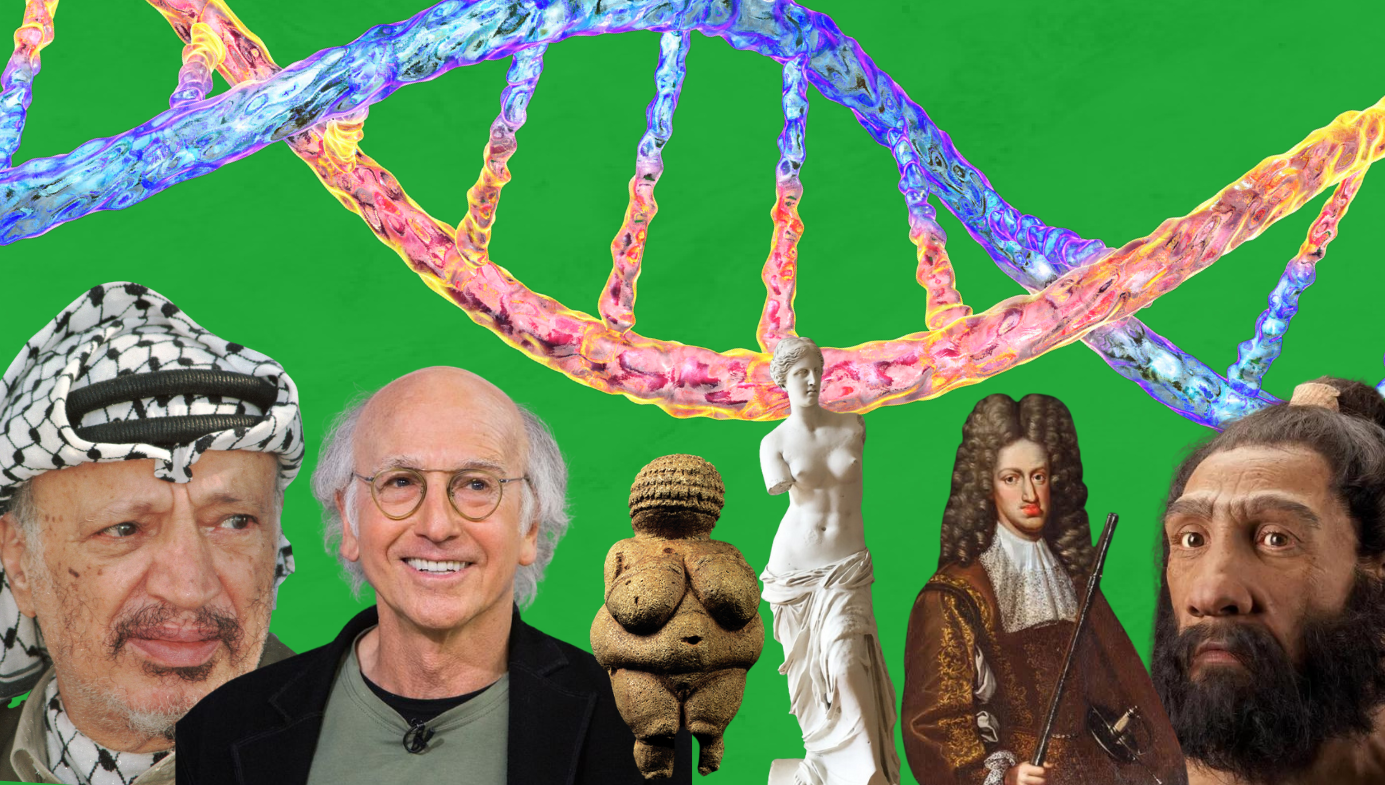

The surprising first step on this path to collapse is prosperity. A civilisation in its infancy, when the benefits of expansion far outweigh the costs, will prosper. However, expansion increases complexity, which requires greater energy and investment to sustain itself. Unable to retreat, civilisations invest more resources expanding, even as marginal returns on this growth keep declining. As the Roman Empire grew, the benefits of conquest declined as administrative and defence costs escalated. Between the third and fifth centuries, this led to increased taxation, increased regulation, expanding bureaucracy, and a debasing of the currency. When the return on complexity became unsustainable, the empire collapsed.

The historian Joseph A. Tainter summarised this process as follows: “Civilisation emerges with complexity, exists because of it, and disappears when complexity does.” This disappearance is marked by the erosion of central authority, depopulation, escalating lawlessness, and the loss of infrastructure. Tainter concluded that while “long-term equilibrium may be possible in comparatively simple foraging societies that are demographically flexible, it is less likely in more complex settings of greater density.” The philosopher Immanuel Kant saw this process as inherent in nature, where “a continual ascent towards the more and more elaborately complex” is followed by “a treading back on its own steps, towards the simple and elementary.”

One of the key drivers of this collapse is elite over-production and the resulting intra-elite competition for increasingly scarce resources. These resources can be material (such as access to opportunity) or symbolic (such as status, righteousness, etc.). The scientist Peter Turchin argued that a civilisation depends on internal cohesion to sustain itself. The Islamic philosopher Ibn Khaldun called this cohesion asabiya, which refers to the capacity of a civilisation for collective action based on a shared sense of purpose and manageable inequality.

However, as civilisations grow, elites become more remote from the masses. They imagine that their wealth, status, and power give them permission to hold the masses in contempt. This narcissism leads to a catastrophic decline in asabiya. Where the disparity between elites and the masses is small, asabiya will be great. As civilisations expand, that gap widens and leads to internal collapse. During the early Roman Republic, the richest one percent were 10 to 20 times richer than the average citizen; in the last years of the empire, imperial senators were 100 times wealthier than their citizens. As conquests eventually led to diminishing economic returns, such wealth and inequality became unsustainable.

In the West, and in the United States in particular, asabiya is virtually non-existent. Elites have migrated to their warring tribes and will stay there until the edifice that supports them collapses. The subsequent reduction in complexity will lead to the re-emergence of simpler forms of social and political organisation. Such is the cycle of growth, inequality, decline, elite over-production, civil war, and collapse. According to this logic, history is not the story of linear progress but of recurrent cycles of growth and collapse, peace and war, as described by the writer George Puttenham in 1589: “Peace makes plentie, plentie makes pride, pride breeds quarrel, and quarrel breeds warre: War brings spoile and spoile povertie, povertie pacience and pacience peace: So peace brings warre and warre brings peace.”

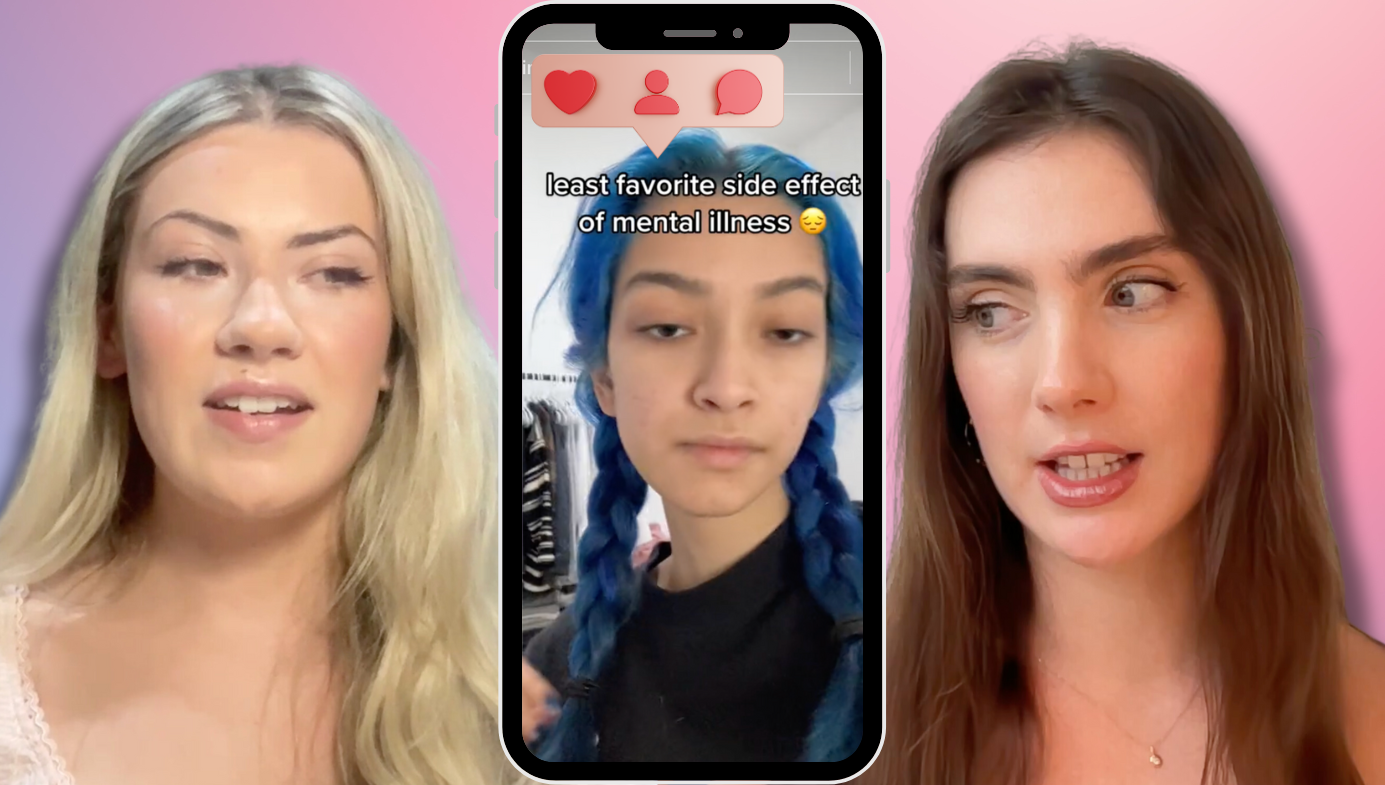

If, as Paul Valéry suggested, civilisations and individuals share the same fragility, it’s because the great impersonal forces of history are the product of the actions of individuals. If increasing complexity creates unsustainable pressure for civilisations, the crack-up is its individual equivalent. Depression, addiction, narcissism, psychosis, the myriad mental health crises that devastate our identities—these all occur when emotional pressure becomes too much for us to bear, when more is demanded of us than we are psychologically able to withstand. While the origin of these crack-ups is internal, the feeling is one of helplessness, of being driven by external forces, or what Fitzgerald described as “being an unwilling witness of an execution, the disintegration of one’s own personality.”

The collapse of civilisation and the disintegration of the Self both involve the detachment of parts from the whole and a consequent loss of structural stability. It’s this loss that Enlightenment rationalism sought to prevent through the creation of a rationally ordered system. In 1739, the empiricist David Hume described personal identity as “a bundle or collection of different perceptions … in a perpetual flux and movement.” The philosopher Gilles Deleuze called this flux a world in which “we bathe in delirium.” Horrified by such chaos, Immanuel Kant responded by claiming the Self ordered experience before it happened. He saw a stable, rational Self as our only hope for “perpetual peace,” firm in his conviction that the unity of the individual will lead to the “collective unity of all wills.”

Kant saw the French Revolution as “the first practical triumph” of this vision. He chided a sceptical friend, saying, “I have seen the glory of the world.” Yet, as Kant completed his third great Critique in 1793, Maximilien Robespierre sanctioned the Great Terror. A carnival of severed heads followed. Kant, like Fitzgerald, became “an unwilling witness to an execution” as the “glory of the world” expressed itself in bloodshed. Utopian ideologies, such as the Republic of Virtue, arise as an attempt to simplify unmanageable complexity. They’re also a horrifying symptom of collapse.

Individually and collectively, collapse leads to a nihilistic tribalism clothed in moral idealism where decline in asabiya can be measured in the degree to which conflict between identities gives way to conflict within an identity. This war of an identity against itself defines what it means to crack up. It’s a total loss of order in which institutions crumble. As these structures disintegrate, mutually incomprehending and unstable identities proliferate. Fitzgerald described the crack-up as “my self-immolation,” which “was something sodden-dark where there was not an ‘I’ any more—not a basis on which I could organise my self-respect.”

And yet, even as we are surrounded by the ruins of our individual and collective identity, we persist in denial. The magnitude of this wilful blindness necessarily coincides with elevated grandiosity. The Late Classic period of the Mayan civilisation was notable for an explosion in monument construction, just as the West’s decline is defined by the extraordinary status-seeking narcissism of its elites. These are symptoms of a struggle against a catastrophic event that’s already underway. The effort to bury such terrifying knowledge is, of necessity, grandiose: it’s when all is lost that we bloat our dreams of glory.

In his last year of sanity, Friedrich Nietzsche wrote some of the finest philosophical works ever produced. As his mind broke beyond repair, he adopted multiple grandiose identities including Dionysus, the Anti-Christ, and Caesar. He fantasised about having the Kaiser, Chancellor Bismarck, and all antisemites shot. Following his final collapse in the Piazza Carlo Alberto in Turin on January 3rd, 1889, he even imagined controlling the elements and promised to “prepare the loveliest weather tomorrow” for a professor who came to take him to a psychiatric clinic.

Of course, Nietzsche had no control over the elements, nor could he shoot the Kaiser. His greatest achievement was to predict, with greater clarity than any other thinker, what happens to individuals and civilisations when the structure that holds them together breaks apart. It was a madman who ran into the town square to announce the death of God. “But how did we do this?” he cried, “How could we drink up the sea? Who gave us the sponge to wipe away the entire horizon? What were we doing when we unchained this earth from its sun? … Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us? Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it?”

What does it mean to “become gods”? Gilles Deleuze explained that “the only change” after the murder of God “is this: instead of being burdened from the outside, man takes the weights and places them on his own back.” This acceptance of an enormous burden is what Nietzsche meant by “bad conscience.” It begins with the internalisation of the burden once imposed on us by God. It ends with the moral simplification of the soul, the purging of what we mistrust in ourselves and the projection of malevolence onto the Other. When this movement is complete, cruelty is endless.

Yet, this moral violence will not protect us from collapse. Rather, it’s a symptom that we’ve already cracked. Like the critic in Fitzgerald’s essay, those who choose the path of accusing the Other are desperate. Too weak to accept responsibility, they want the whole world to crack with them. This extraordinary egotism makes them tyrannical. They spew hate and call it love. They manufacture enemies in order to punish them and call it justice. It’s a frantic struggle for emotional survival that turns malignant.

Fitzgerald captured the final stage of this struggle in the last words of “The Crack-Up”: “I will try to be a correct animal though, and if you throw me a bone with enough meat on it I may even lick your hand.” Helplessness leads to tyranny when we believe the only choice we have is to disintegrate or submit to tyrannical authority as a way of preserving our sanity and moral righteousness. The effect, however, is to accelerate the collapse of the order we seek to preserve: in its End Times, the crack-up means, as Fitzgerald prophesied, “being an unwilling witness of an execution.” Too late, we discover the head rolling on the ground is our own.

In his last years, as his mind disintegrated, Immanuel Kant faced the “devastation and ruin” of his own life. Those who saw him were distressed at his helpless state. Kant described himself as “a poor, worn-out old man.” Yet, many visitors came to his house to pay homage to the greatest philosopher of his time. When they entered, Kant insisted on standing until his guests sat down. His doctors advised him against such exertions, to which Kant replied, “God forbid I should be sunk so low as to forget the offices of humanity.” When faced with our own “devastation and ruin,” can we sustain such offices and, perhaps, make good a solitary fragment of the damage we have done?