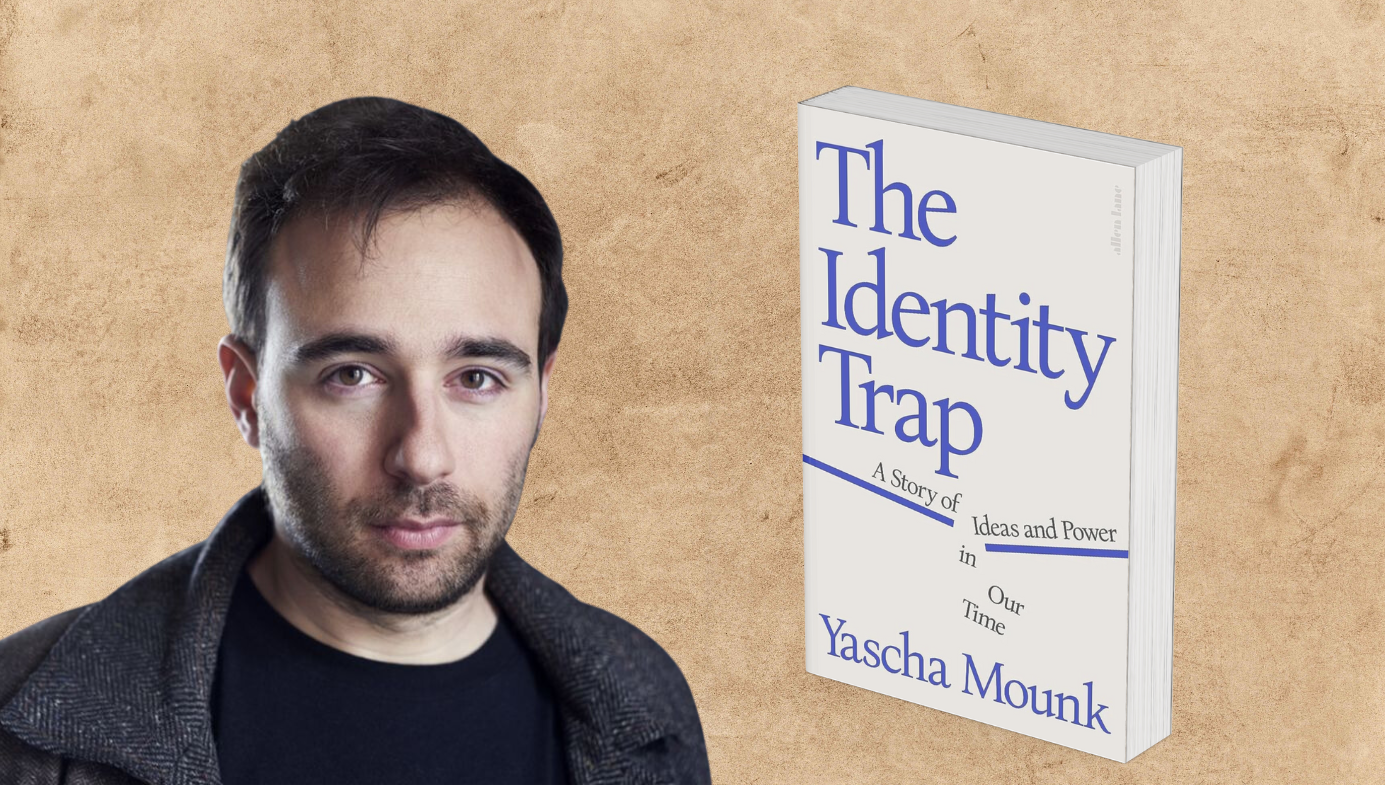

Saving Liberalism from ‘The Identity Trap’: An Interview with Yascha Mounk

In an acclaimed new book, the German-American political scientist traces the rise of illiberal intellectual movements among modern progressives.

Some call it “wokeness”—a word that once felt right but now feels more like an overbroad culture-war term of abuse. Others might call it social-justice extremism. But that seems too charitable: True “social justice” is about helping the world’s poor and (truly) oppressed, whereas the fashionable ideology we’re talking about here is more about privileged westerners demanding correct pronoun usage and race quotas in movie casting. As Yascha Mounk argues in his new Penguin Press book, The Identity Trap, A Story of Ideas and Power in Our Time, this lack of commonly agreed-upon terminology is a problem: How can we coherently oppose an ideology if we can’t even properly describe it?

In his new book, the German-born American political scientist authoritatively traces the evolution of the “identity synthesis” (Spoiler alert: that’s the term he’s come up with to describe the ideology formerly known as wokeness) by reference to the ideas of Karl Marx, Michel Foucault, Edward Said, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Noam Chomsky, and other influential leftist thinkers.

At its root, Mounk argues, the identity synthesis is an illiberal intellectual movement that rejects liberalism’s focus on colorblindness, free speech, individualism, and ideological pluralism—while also rejecting Marxism’s utopian promise of a better future in which society’s class-based divisions are healed.

Instead, the identity synthesis gives us the worst of both worlds. Not only does it attack the freedoms and guarantees of equal treatment promised by liberalism; it does so in the service of a dystopian vision. In this political conception, blacks, Hispanics, women, and LGBT citizens are doomed to suffer some measure of oppression. Meanwhile, privileged members of society—those who are male, white, straight, “cis,” et cetera—are commanded to piously interrogate their political souls in perpetuity.

But if you’re looking for a simple fire-and-brimstone denunciation of the identity synthesis, this book isn’t it. As he demonstrates in the interview that follows—adapted from a recently aired Quillette podcast episode with host Jonathan Kay—Mounk’s analysis is nuanced and balanced. His goal is not merely to critique the identity synthesis, but to explain how leftists came to embrace its dead-end fixation on identity; and to offer ideas about how they can be returned to the path of liberalism.

Jonathan Kay: I enjoyed your discussion of the role of Marxism in the formation of “identity synthesis” ideology, as I think there is a somewhat lazy conservative tendency to label the modern fixation on identity as “cultural Marxism.” If Karl Marx were around today, he’d be horrified to see his name attached to this stuff. Marxism was always conceived as a universalist movement, whereas the identity synthesis is about permanently dividing everyone into groups.

In 1903, there was a famous episode in which Leon Trotsky publicly condemned the Jewish Labour Bund, which was essentially the Jewish wing of the communist movement in Eastern Europe at the time. His position was that organizing communists by religion was a form of isolationism. He saw it as violating the collective universalist spirit that animated Marxism, even though he was a Jew himself.

Oddly, in discussions with proponents of what one might call the identity synthesis, I find myself defending Marx. I think he’d be shocked to see his class-based analysis—as wrongheaded as it was in many ways—compared to today’s parochial identity-based movements.

Yasha Mounk: So I think there are important differences between Marxism and the identity trap. And the first one is implicitly admitted by the people who call it “cultural Marxism”—by the very fact that they’ve tacked on the word “cultural.” Marxism is, by definition, economic. It’s based on class struggle. So when you say “cultural Marxism,” you’re acknowledging that it involves taking out the economic dimension…

JK: Also, the identity synthesis fails to present adherents with even a theoretical possibility for any kind of universalist reconciliation among groups. At least when you have a class-based analysis, you can imagine using the levers of state to bring different socioeconomic groups together—by force if necessary, as history tragically demonstrates. But you can’t forcibly change someone’s skin color.

YM: Right. There is a promise of a post-revolutionary utopia in Marxism, which is absent from the identity trap. Marxists say there’s going to be a revolution. And then, well, a little bit of a black box, and then, boom, no more classes. This was a liberatory promise. When you ask a Marxist what society he wishes for, it’s not a society where the bourgeoisie are hounded every day forever. They imagine a post-class society where we’re all brothers, where we all can stand in solidarity with each other, where there’s no longer a need to go and lock up the bourgeoisie because the bourgeoisie have become proletarians like everybody else.

What’s interesting about the identity synthesis is that it’s completely thrown out that kind of hopeful vision. That’s why many progressives who embrace this idea recoil when liberals suggest that we should aim for a “post-racial” society where everyone is treated equally. No, what identity-synthesis adherents want is a society in which the way we treat each other, and the way the state treats us, should explicitly depend on the kind of group of which we’re a part.

And there’s a third difference between Marxism and the identity synthesis, which can be found in the intellectual history of this movement. The identity synthesis originates in thinkers such as Michel Foucault, who explicitly rejected Marxism, and, in fact, is still seen as an enemy by many Marxists.

JK: Foucault was obsessed with the idea of power and oppression. As you note in your book, he saw these as ubiquitous and inevitable features of any political system. And so he was suspicious of any kind of meta-narrative, or any kind of heroic intellectual movement, that promised to deliver people from oppression, which he saw as being deeply embedded in religion, media, and culture.

YM: There are a few fundamental ideas produced by Foucault that, in popularized form, really have come to deeply influence modern progressive thought. This includes Foucault’s rejection of the idea of absolute truth and “grand narratives”—including not only communism but also philosophical liberalism. He thinks one system of beliefs is inevitably going to be as oppressive as the next.

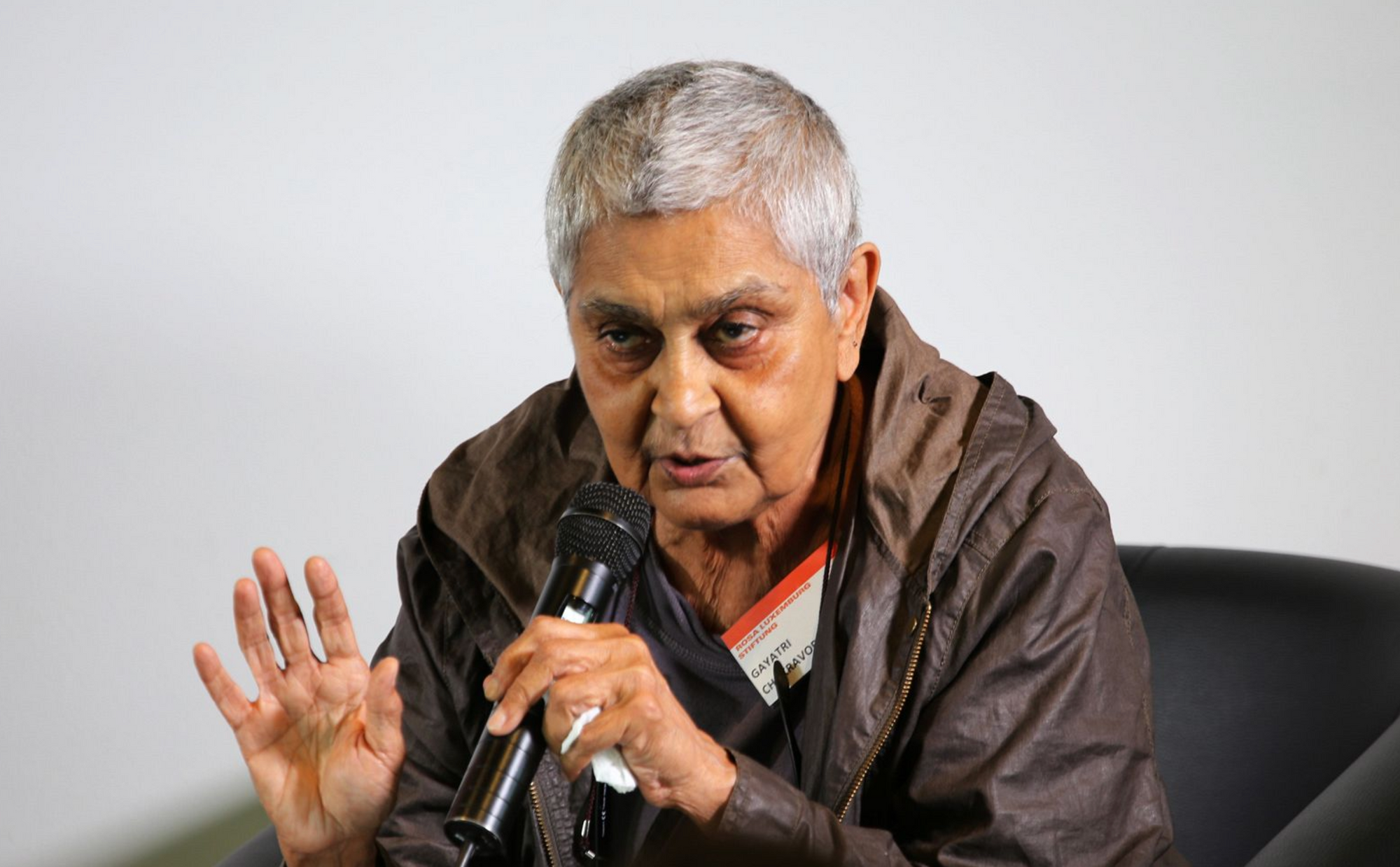

JK: On the issue of how Foucault’s arid, apolitical intellectual ideas got politically weaponized, I was fascinated by your section on Indian scholar Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak and her concept of “strategic essentialism.” Could you explain why she played such a critical role in getting us to this identity-synthesis moment?

YM: As we’ve discussed, it starts with Foucault, who put in place some of the basic intellectual foundations—the skepticism of truth, the rejection of grand narratives, including liberalism and Marxism, the close attention paid to the inherently oppressive nature of political “discourses.”

Then along comes Edward Said, who says, in effect, “Look, it’s absolutely right that we should care about ‘discourses.’ But the point should be to change the way discourses are used as a tool of political power.” He rejected the apolitical aspects of Foucault’s ideas. And that gets us to Spivak’s theory of “strategic essentialism.”

Spivak (b. 1942) is originally from Calcutta. She became deeply concerned about what she calls the “subaltern”—the poorest, most oppressed people in the world. As a poststructuralist, she bought into Foucault’s skepticism about creating basic identity categories and assigning characteristics to them. But she also knew that if intellectuals, such as Spivak herself, were going to speak on behalf of the subaltern and other oppressed groups, any reluctance to assign “essential” characteristics to this or that category of humanity wasn’t politically practical. That’s how she got to “strategic essentialism.”

“Essentialism” means taking for granted the idea of what a group is. It means thinking that there’s something called white people, and something called black people, and something called Latino people, and so forth; and that there’s some rational way in which we can ascribe people to these groups. Spivak rejected this idea philosophically. But she argued for its adoption as a strategic imperative—as a means to allow people to speak on behalf of these groups.

And this tactic—rejecting essentialism in one context, but embracing it in another—has become hugely influential in forging the identity synthesis. When you take, say, any kind of anti-racism training on a college campus, you’re going to hear the speaker say that race is a social construct that’s totally fake. But then the speaker will tell you that, even so, we still have to pay extremely close attention to race—despite the fact that it doesn’t really exist.

JK: Another fascinating figure you discuss is Derrick Bell, a pioneering African-American thinker and civil-rights activist. As I read your book, I started to appreciate Bell as a kind of proto-critical race theorist, because he seems to have developed a lot of CRT-like ideas before that doctrine was formalized with that term.

At first, Bell was a supporter of basic liberal civil-rights ideas, such as colour-blindness and desegregation. But over time, he came to be skeptical of efforts to desegregate schools. As soon as you desegregated a school, he noticed, other things happened: The white parents whose kids went to the school would move to the suburbs, or maybe the school gets shut down or defunded. In other words, the white power structure finds a way to punish black families. And so desegregation didn’t help as much as white civil-rights activists wanted to believe.

Moreover, when Bell talked to black parents, he found that what they really wanted was simply good schools for their kids. They didn’t care as much if it was a black school or a white school. What they cared about was that their kids were getting a good education. This implies a policy response that focuses more on giving black people more resources to remedy the racism they continue to experience, with less focus on the ideologically formulated liberal goal of desegregation for its own sake.

Reading this, it struck me that today’s progressive rejection of civil-rights era liberalism isn’t a new thing. In some ways, it really goes back to the civil-rights era itself.

YM: Yes, Bell is a really interesting figure. He did work with the NAACP to desegregate schools and businesses and other institutions throughout the American South in the 1960s, and aspired to become a lifelong civil-rights lawyer. But then he started to notice that desegregation didn’t always work. And, scandalously, he even came to cite conservative segregationists sometimes—as he shared their critique of civil-rights lawyers who would come sweeping into a town wanting to desegregate the schools because it aligned with their liberal ideology. As Bell saw it, the best result was often to have black schools that were as good as the white schools. He explicitly rejected what he came to call “defunct racial-equality ideology.”

All of this, of course, runs directly contrary to the black liberal tradition, which starts with Frederick Douglass and includes Martin Luther King. Douglass didn’t dismiss liberal values as false. He simply attacked the racist hypocrisy by which those liberal values weren’t extended to black people.

JK: You have a good section on Barack Obama, which really made me think hard about his legacy. At the time, he was the most liberal president in the history of the United States. But in retrospect, he’s actually—somewhat weirdly—kind of a conservative figure, in the sense that he explicitly embraced (and continues to embrace, apparently) the traditional liberalism of Frederick Douglass.

YM: Yes. In fact, supporters of critical race theory have been explicit in saying, as law professor Kimberlé Crenshaw put it a decade ago, that Obama was always fundamentally at odds with the basic tenets of CRT. He wanted to move America toward a post-racial society, which is of course directly at odds with the identity synthesis.

JK: When you discuss the effect of digital technology on the formation of the identity synthesis, you use Tumblr as an important case study. Can you explain why?

YM: Tumblr is a kind of micro-blogging service where you can have little videos, memes, and audio. It was very popular among teenagers in the late 2000s and 2010s. And one of the key things that it allowed people to do—which, for example, Facebook didn’t at the time—was to self-organize by a topic tag. So you could look at everybody who’d posted under a particular kind of term.

JK: Like, say, “genderfluid,” for instance.

YM: Exactly. And so what that did was to radically expand the set of identities by which you could define yourself. If you time-travel back to a high school in the pre-internet 1990s, the tribal identities you could choose for yourself were limited, since, in any given school, there had to be a minimum of maybe two percent of the population who shared your identity. And so the identity you picked couldn’t be too obscure, or you wouldn’t really have anyone else in your group.

On Tumblr, however, you were drawing from a pool of millions. And so you could find other people who shared your form of self-identification even in the case of very rare identities. You saw a lot of this with gender and sexuality.

JK: You have an interesting quote in your book, which I hadn’t seen before, from someone named Zach Goldberg, a doctoral student in political science at Georgia State University, about how, during the 2010s, certain phrases and words “went from being obscure fragments of academic jargon to commonplace journalistic language”—terms such as microagression and intersectionality. Is this because all those teenagers with Tumblr accounts grew up and got jobs in the media?

YM: Both Ezra Klein and Matthew Yglesias have talked in interesting ways about how when Vox was founded by them in 2013, most of its traffic came from the site’s home page. And so anything on the site had to appeal to a pretty broad audience. What happened around 2015 and 2016 is that most of the traffic started to run through social media instead. So suddenly, most of the traffic you’re getting is from people who click on something on Facebook.

That means you no longer had the same constraints on what gets published. It doesn’t matter if nine out of ten Vox articles are too obscure for the average Vox reader, because you don’t have this landing page that everybody goes to in order to find what they’re going to read. Instead, they’re coming to the site through their social-media silos. So you can write an article about something that has a strong political-cause-based network or identity-group-based network on social media—and that article will spread virally within those milieus.

At the same time, of course, newspapers such as The New York Times and the Washington Post were under tremendous economic pressure because they had this cratering ad revenue, and they needed clicks desperately. So how do they get clicks? By hiring a lot of the graduates from web sites such as Vox.

So you get this fascinating transformation of Vox itself from a kind of technocratic liberalism to a much more first-person, progressive, identity-driven site. The Times and the Post go in the same direction, which is why you start to get a lot more articles about white privilege and so on.

JK: The last chapter of your book is a kind of guide aimed at helping readers advocate for liberalism in the face of the identity synthesis’ illiberal tendencies. I have to admit that I’m somewhat pessimistic when it comes to this cause.

My view is that history shows us that liberalism, while imperfect, is better than all the other alternatives. Unfortunately, the communications tools and political rights that liberalism gives us also serve to amplify our complaints about liberalism. And the Internet has turbocharged that.

If you’re a progressive and you go on Twitter, you’ll see seventeen videos of police officers beating black people. And you ask yourself: How can anyone defend a liberal order of things when this kind of thing happens?

Similarly, if you’re a conservative, and you go on social media, your conservative friends will show you seventeen videos of, I don’t know, illegal immigrants doing horrible things. And so you become fired up with populist rage, and you say, “Well, if liberalism means having this kind of multicultural society, screw that.”

In both cases, the emotional immediacy of internet-propelled outrage porn amplifies the pre-existing vulnerability of liberalism to attacks based on its inevitable imperfections. In the long run, I’m not sure liberalism wins this war.

YM: I think that, at root, we live in a liberal culture. And when institutions violate basic liberal norms, there is a healthy moral instinct at play whereby most of us eventually realize that something’s gone wrong.

And I’ve seen that among my friends. I have an acquaintance who was always skeptical when I would discuss some of the shortcomings of the identity trap. She was much more progressive than I am, and she’d just be like, “Oh, Yascha’s going off on this thing again.”

But then when I saw this friend after the pandemic, I learned that the organization that she’s a part of had torn itself apart over the last few years in all sorts of ways. She saw me at a gathering, and made a beeline straight for me and said, “Yascha, I finally get what you’ve been talking about.”

I think this is going to be a real intellectual battle for the next twenty years. And I agree that the outcome is not foreordained. The reason I wrote this book is that the result of this battle will turn on whether we are able to make the right arguments, and to argue against illiberal ideas, with full hearts and clear minds.