The Wrongful Exoneration of Adnan Syed Part I: A Straightforward Murder Case

A serious reexamination of this case must begin by setting out the evidence that led the jury to convict.

Among competing hypotheses, the one with the fewest assumptions should be preferred.

~Occam’s Razor

On September 19th, 2022, Adnan Syed walked out of a Baltimore courtroom a free man. In 2000, when he was just 18 years old, Syed had been convicted of murdering his 18-year-old ex-girlfriend Hae Min Lee. The Supreme Court of Maryland had rejected the last of his many appeals in 2019, and he had not been pardoned or granted parole. Syed was free because the Baltimore State’s Attorney’s Office, which had originally prosecuted him and had zealously defended his conviction for over two decades, had suddenly decided to reverse course. The decision was entirely unexpected.

Lee’s surviving family were shocked, but Syed’s supporters were jubilant. He left the court amid a throng of cheering fans with his criminal record expunged—he was no longer a convicted murderer. A few weeks later, Baltimore officially confirmed that it would not prosecute him again. But that was not to be the final twist in the case. In late March 2023, Adnan’s conviction was reinstated by an appeals court. The court stayed its judgment for 60 days to let the parties contemplate next steps. Thus, as of this date, Adnan Syed remains a convicted murderer who lost his appeals, was neither pardoned nor paroled, and is not even technically free on bail. Nevertheless, he is at liberty to move freely, and to go to his job at Georgetown University every day. He is almost certainly the only person in America who finds himself in this unique and paradoxical situation. His might be the only such case in American history.

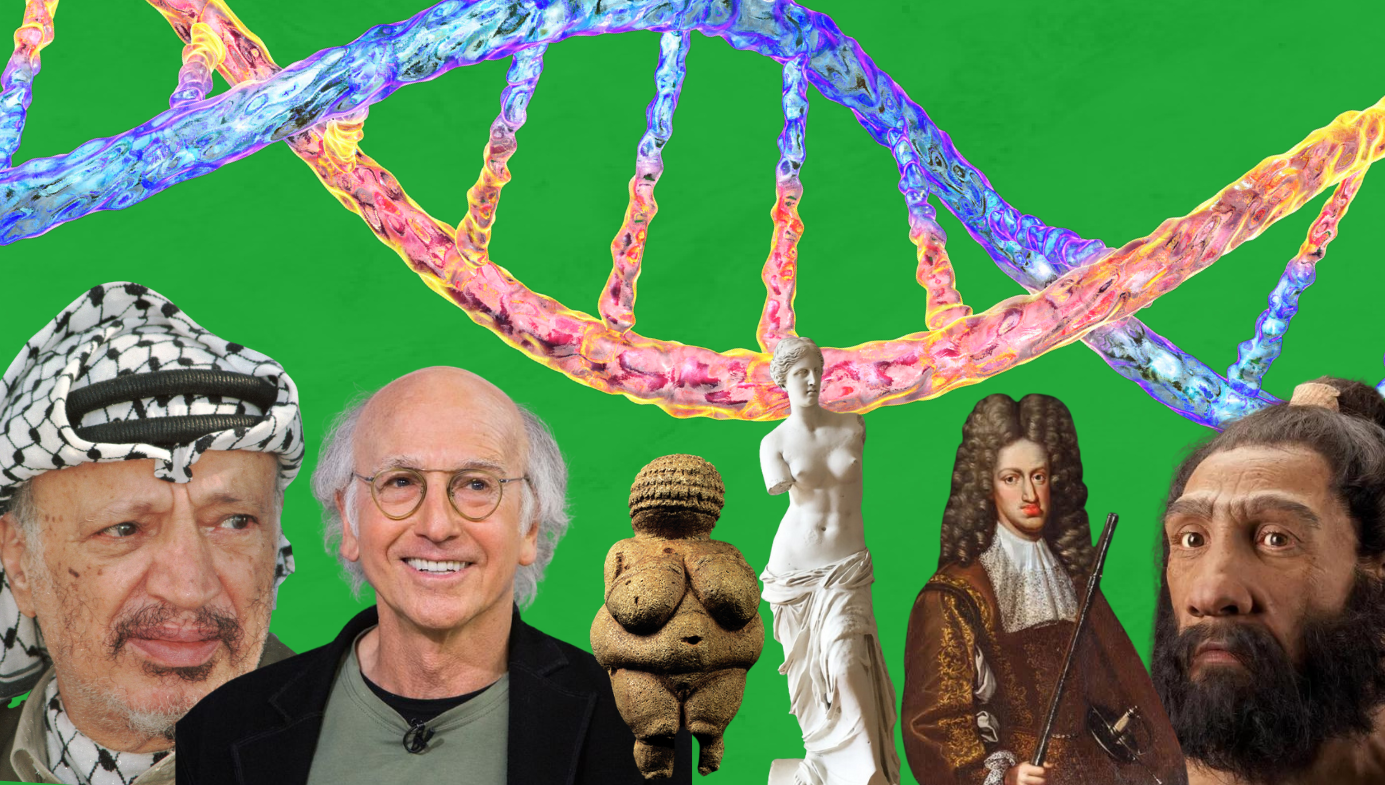

Adnan Syed landed in this unique situation because he is a world-famous celebrity, and he became a world-famous celebrity because of a humble podcast. Three hundred million people have downloaded Serial, a 2014 American podcast about his trial that purported to raise troubling questions about his conviction. The success of that series helped trigger a tsunami of true-crime media, from basement-rant Serial imitators to glossy Netflix productions. It was also followed by further re-investigations of Hae Min Lee’s murder—more podcasts and documentaries have bobbed along in Serial’s expansive wake. The result? A straightforward 1999 murder case has, according to the Washington Post, “arguably received more attention, review and support than any other criminal case, ever.”

Followers of this story have explored everything from high-school wrestling schedules and the structure of plastic automobile parts to the minutiae of Ramadan prayer practices. The case also spawned two online armies, self-described as “guilters” and “innocenters,” who trade diatribes and deploy doxxing, litigation, and calumny to build their respective cases and undermine their opponents. The level of infighting, skulduggery, and betrayal within and between these groups makes the election of a Borgia pope look like a school play.

The State of Maryland v. Adnan Syed has become a touchstone in American social history comparable to the trials of the Scottsboro Boys, Sacco and Vanzetti, or the Rosenbergs. The case poses big questions: Was the investigation of Adnan Syed infected by Islamophobia? Did police and prosecutors overreach? Do appeals courts truly test convictions, or are their opinions window-dressing? Are 17-year-olds mature enough to be sentenced as adults? Should testimony from unreliable accomplices with mixed motives be admitted in court? How reliable is human memory? Can you judge a person’s capacity for evil from their appearance and demeanour?

The fog of controversy has tended to obscure a simpler and more important question: Did Adnan Syed strangle Hae Min Lee to death? Everyone says they want to answer this question, but the big media productions and podcasts have repeatedly failed to present the evidence against Syed fully and forthrightly. Among the major productions, only Serial even gestured at the evidence implicating Syed, but its makers only got around to setting (some of) that evidence out in Episode 6 of a 12-episode series which begins with an episode entitled “The Alibi” and moves right on to “The Inconsistencies.” That’s not how Baltimore jurors heard the case before they convicted the accused after just two hours of deliberation. They stand by that decision to this day.

So, a serious reexamination of this case must begin by setting out the evidence that led the jury to convict, including the many facts elided by Syed’s advocates. That is what Part I of this two-part essay will do. Serial used first names for the main figures in the case (most of whom were teenagers when the crime was committed), and in what follows, I’ll do the same. Shorter documents will be linked to in whole, while citations from longer documents will be identified by the .pdf page number (e.g., “39p”).

Let’s begin.

I. Adnan Syed and Hae Min Lee

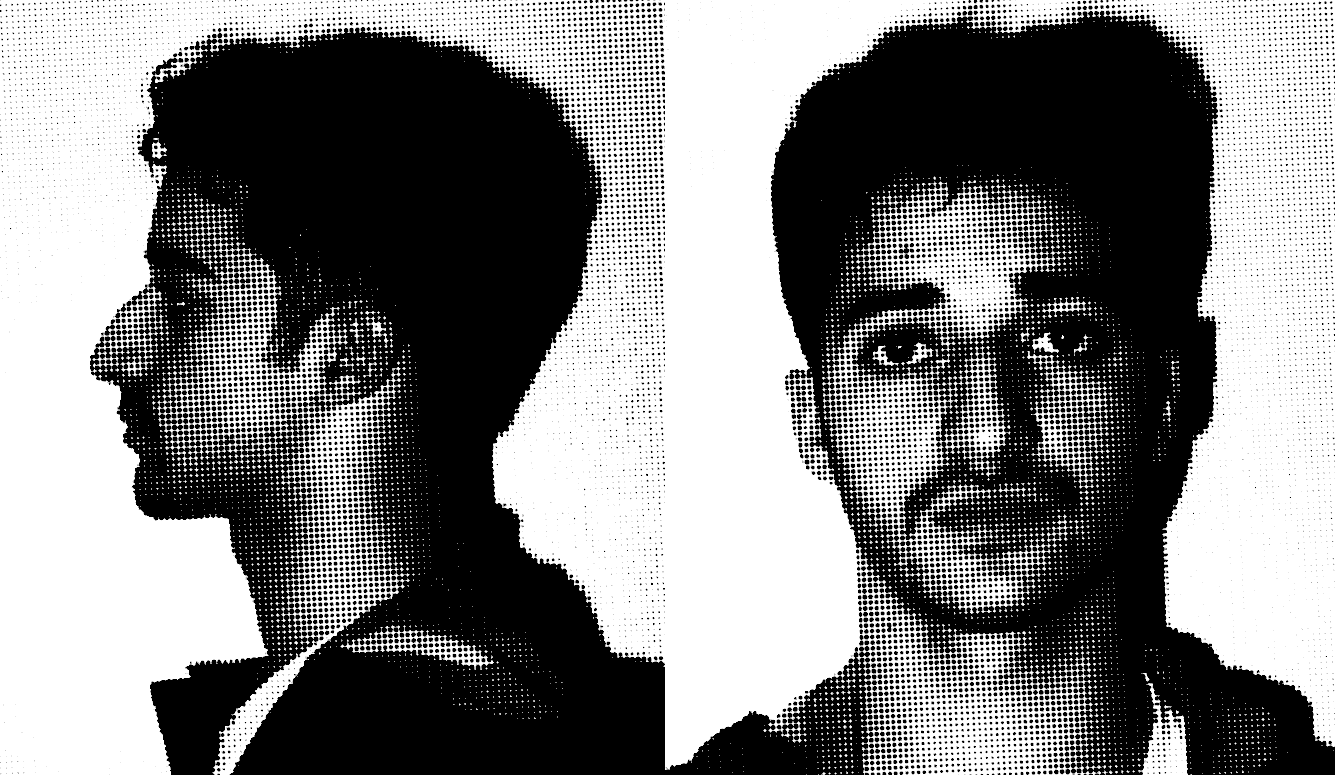

In January 1999, Hae Min Lee and Adnan Syed were seniors at Woodlawn High School in Baltimore County, Maryland. Baltimore County surrounds the City of Baltimore, and this is an important geographic distinction. The City of Baltimore—the setting of the HBO series The Wire—has faced difficulties for decades. Randy Newman wrote a song about it in 1977. Baltimore County, meanwhile, is lower middle class and diverse, and many immigrant families live there in apartments or cheap homes. When Hae disappeared on January 13th, 1999, she was 18 years old. Adnan was 17 years old and would turn 18 on May 21st, 1999. In prison.

Adnan’s family is of Pakistani extraction. His father’s name is Syed Rahman (in some Pakistani families, sons adopt their father’s forename as their own last names, which is why Adnan and his father do not share a common surname). Rahman emigrated to the United States in 1971, where he later married his wife Shamim. Adnan was born in Baltimore in 1981, and was thus an American citizen from birth. Adnan’s parents speak sound but unpolished English. His father, a civil engineer, worked as an inspector for the State of Maryland, while Shamim ran a day-care centre from the family home. Adnan has two brothers, the older of whom is named Tanveer. Hae Min Lee’s family is of Korean origin; she was born in South Korea in 1980 and emigrated to the United States with her family in 1991. In 1999, Hae was a Korean citizen with a permanent residency permit (green card) who lived with her mother and her younger brother, Young Lee.

In 1999, Woodlawn High School hosted a “magnet” program intended to gather gifted students into a stimulating environment. Magnet students were a minority of students at Woodlawn (the others were not part of the program), and Adnan and Hae were both admitted to Woodlawn’s magnet program in 1995. They took many classes together and became friends. Both were bright, accomplished, driven, and popular. Hae thought of becoming an optician and worked at a chain of eyeglass stores called LensCrafters. Adnan planned to study medicine and worked part-time as a paramedic, even though he was underage.

Hae and Adnan began dating in March 1998 and fell in love. Hae kept a diary—later admitted into evidence at trial and now available in full on the Internet—in which she recorded her feelings for Adnan but lamented the problems their relationship caused him. His conservative parents frowned on casual dating, to say nothing of premarital sex, so the young couple had to invent cover stories for their liaisons.

The relationship was turbulent, and there were multiple break-ups, all initiated by Hae. In her diary, Lee occasionally described Adnan as possessive, jealous, and overprotective, comments she also made to friends. Hae once told her French teacher Hope Schab, for whom she worked as a teaching assistant, that she would be late because she and Adnan had had a fight and she was trying to avoid him. Schab also told police that Hae’s friends told her that Adnan could be “very controlling, paging [Hae], checking up on her.” In her diary, Hae wrote that Adnan frequently asked her to account for her time and complained that she did not respond quickly enough when he paged her.

Debbie Warren, a close friend of both Hae and Adnan, testified at Adnan’s trial in February 2000. She said that she had observed no violence in their relationship and that Adnan could be charming, had deep feelings for Hae, and seemed to take their breakups in his stride. But Debbie also testified (40p) that, “Adnan was very over protective of Hae. He never made her sustain [sic] from seeing her friends but he did suggest that she spend more time with him. He wanted to know where she was going, when she was going, who she was with, almost like he was her father…” Asked what additional issues there were besides Adnan’s religion, Debbie said: “The control issue between the two of them and his possessiveness, his aggressiveness verbally, and him keeping tabs on her all of the time, that really irked her and she felt like she wasn’t free in the relationship.”

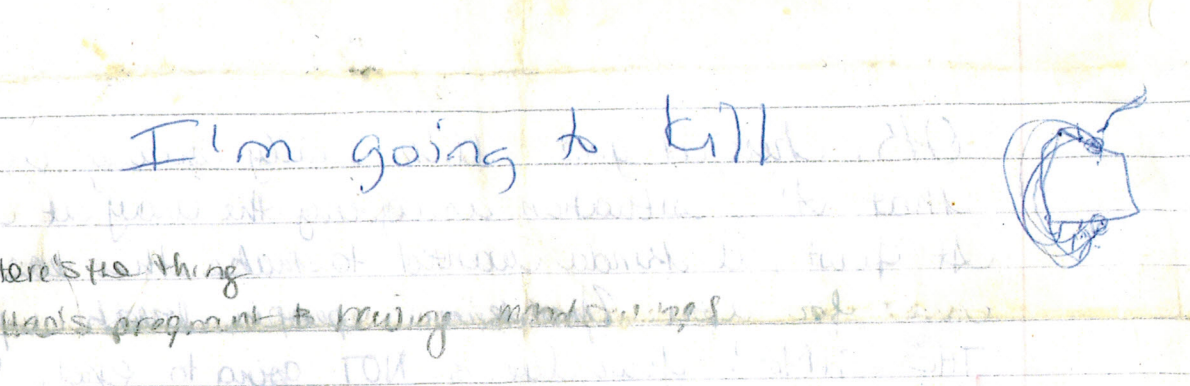

Hae’s diary reveals her growing conviction that the relationship had no future. He was possessive toward her but he would not level with his parents about their relationship. She also worried that she might be pulling him away from his faith. The relationship foundered in late 1998. When police searched Adnan’s house on March 20th, 1999, they found an undated letter from Hae to Adnan about their penultimate breakup in early November 1998: “Your life is NOT going to end. You’ll move on and I’ll move on. But, apparently you don’t respect me enough to accept my decision. … I NEVER wanted to end like this, so hostile + cold. Hate me if you will. But you should remember that I could never hate you.” Adnan’s friend Ja’uan Gordon later told police that when Adnan read this letter he was “mad about letter eyes watering face flush.” On the back of that letter Adnan at some point wrote: “I’m going to kill.”

Nevertheless, the November breakup was not the final breach. That came on December 23rd, 1998. In the new year, Hae began openly dating Don Clinedinst, one of her LensCrafters co-workers. Hae and Don had long flirted and they became a couple in late December 1998. Hae’s diary included a passage written just before her death in which she wrote Don’s name 127 times, counted them, and then wrote: “127 Dons!” Around New Year’s Eve 1998, she changed her AOL profile:

Interests: Movies, Phone, Partying, TV, Music and most importantly Don. Likes: Looking into his blue eyes, fast cars like his Camaro, … Occupation: Part-time sales, Full-time Girlfriend. “I love you and I miss you Donnie.” Libra

Adnan would almost certainly have seen this profile in early January 1999.

Adnan smoked marijuana, which was not uncommon among suburban high-school students in 1999. He bought weed from his friend Jay Wilds, a young black man who had graduated from Woodlawn in 1998. In January 1999, Jay’s girlfriend was Stephanie, a beautiful 18-year-old then still in the Woodlawn magnet program, and he visited Woodlawn on occasion to hang out with her and her friends. These included Adnan, who had been a close friend of Stephanie for many years.

On January 12th, 1999, Adnan activated his first cell phone. At that time, adults had to sign off on permits for minors to buy a cell phone. That adult was Bilal Ahmed. At that time, Bilal was a dentistry student and a youth counsellor at a Baltimore County mosque (also known as the Islamic Society of Baltimore). Adnan’s family lived on the same street as this mosque, Johnnycake Road, and attended regularly along with many other families.

In early 1999, a cell phone would have been a prize possession for a middle-class American teenager. After activating it on January 12th, Syed used it dozens of times every day until his arrest. In 1999, accurate GPS was still reserved for the military. Adnan likely understood that the numbers he called left some kind of record, but there is no evidence he realized that cell signals could yield an approximate location of the phone during calls. This would prove to be a fateful oversight.

II. Hae Min Lee disappears

On or around Monday, January 11th, 1999, Adnan learned that Hae had not merely dumped him and begun dating Don, but also that she had started sleeping with him. Hae was smitten and had told many people at Woodlawn how well her new relationship was going. She told friends that she had spent the night (2p) at Don’s house early in the week of January 11th; Don also confirmed (88p) that they had “been intimate” shortly before she was killed. Hae had also told her confidante, French teacher Hope Schab (32p), about the new relationship, as well as Inez Butler, a teacher and athletics instructor (12p) at the school.

In the final hours of January 12th, 1999, and the early hours of January 13th, Hae spoke on the phone to Don for hours. “I love you Don,” she wrote in her diary. “I think I have found my soul mate. I love you so much. I fell in love with you the moment I opened my eyes to see you in the breakroom for the first time.” Adnan called Hae twice on her family’s landline, at 11.27pm and 12.01am. Each call lasted just two seconds. He finally reached her at 12.35am on the morning of the 13th, the day she would die. That call lasted for a minute and 24 seconds. Hae wrote down Adnan’s new cell phone number in her diary, without identifying its owner.

On February 11th, 1999, two days after Hae’s body had been discovered, Adnan told Woodlawn school nurse Sharon Watts (3p) that on the night before Hae was killed, she had called him to say she wanted to get back together. When he made this claim, he could not have known that Hae was documenting her love for Don at the time. Adnan only discovered the contents of Hae’s diary during his trial. This is one of several lies Adnan told about his relationship with Hae and his actions on January 13th. A more plausible explanation for this short call might be that Adnan was asking Hae for a ride after school the next day, which was a common occurrence even after their breakup.

Krista Meyers, a student who was a friend of both Adnan and Hae, testified that she heard Adnan ask Hae for a ride after school on the morning of Wednesday, January 13th. According to Krista’s trial testimony, Adnan said he needed a ride (4p) from Hae after school to collect his car because it was either being repaired or Adnan’s brother had it (she couldn’t recall which). This was untrue. On the morning of the 13th, Adnan called Jay at home and offered to let him borrow his car and cell phone (Jay had neither) while Adnan was at school. Adnan had never allowed Jay to borrow his car before. He said he would call Jay later (on Adnan’s own cell phone) so Jay could pick him up in Adnan’s car from wherever he might be.

School ended at 2.15pm, although some students stayed on campus to study or attend sports practice. Aisha Pittman, another mutual friend of Adnan’s and Hae’s, testified that (15p) she saw Adnan talking to Hae around this time. Woodlawn had some 1,600 students, so the end of school was a roiling exodus of students and staff streaming into buses and getting into cars. Hae’s departure was not recorded on any surveillance cameras. She had promised to pick up her young cousin at a day-care centre at around 3.00pm, something she did every weekday. She missed that appointment and was never seen alive again.

Hae would also miss her shift at LensCrafters at 6.00pm, by which time her family had already raised the alarm. Young Lee filed a missing-person report for Hae at 5.12pm. Police would ordinarily have waited before investigating, since Hae was an adult. However, a few months before her disappearance, a young student from a nearby high school, Jada Lambert, had been raped and murdered, a case which would not be solved until a 2002 DNA match. So police had begun investigating disappearances of young women with greater urgency than normal. Young Lee located Hae’s diary and called the phone number scrawled near the latest entry about Don. Adnan answered.

When Young Lee realised he was talking to Adnan, he asked where Hae was. Adnan said he didn’t know. By this time, Baltimore Missing Persons Unit police officer Scott Adcock had arrived at the Lee home. Adcock called Hae’s friend Aisha, who told him she had heard from Krista that Hae was supposed to give Adnan a ride after school. Officer Adcock called Adnan’s phone at 6.24pm. The call lasted four minutes and 15 seconds. Adcock informed Adnan that witnesses had reported Adnan asking Hae for a ride. At trial, Adcock testified (consistent with his earlier police report): “[Adnan] advised me that he did see her at school and that Ms. Lee was going to give him a ride home from school, but he got detained and felt that she probably got tired of waiting for him and left.”

After initially getting no answer at Don Clinedinst’s home (Clinedinst later said he had felt ill after his LensCrafters shift and taken a nap), Adcock finally reached Don at 1.30am on the morning of the 14th. Clinedinst said he had last spoken to Hae on January 12th and did not know where she might be. In the following weeks, police interviewed Woodlawn teachers and Hae’s friends. Initially, few suspected foul play. Perhaps Hae was staying with friends or had flown to California to visit relatives. Joseph O’Shea, a detective with the Missing Persons Unit, visited Adnan Syed’s home on January 25th, 1999, while Adnan was at school. O’Shea left his card, and Adnan called him back. When asked about the 13th, Adnan said (according to O’Shea’s trial testimony): “[H]e was in class with her that day from I believe it was 12:50 p.m. till 2:15 p.m. He did not see her after school because he had gone to track practice.”

When O’Shea reviewed Officer Adcock’s report and noticed the discrepancy, he called Adnan on his cell phone on February 1st, 1999. As O’Shea testified: “I asked Adnan if he told Officer Adcock that Hae was waiting to give him a ride on the 13th. Adnan told me that was incorrect because he drives his own car to school so he wouldn’t have needed a ride from her.” O’Shea tried to schedule an in-person interview with Adnan (then still a minor) at home, but Adnan said he didn’t want his parents to be present due to the sensitive nature of his relationship with Hae. He asked if his older brother could be present instead and O’Shea agreed. A meeting was scheduled for February 10th.

III. From missing person to murder victim

That interview never took place, because Hae Min Lee’s body was discovered in Leakin Park on February 9th, 1999, by Alonzo Sellers, a maintenance worker employed at nearby Coppin State College. Leakin Park, renowned as a rendezvous for shady transactions and a dumping ground for corpses, is a sprawling, mostly unimproved forest-like park on the outskirts of the City of Baltimore. Sellers told police that he had pulled over to the side of the road while driving back to Coppin College from lunch. He had walked into Leakin Park to urinate and had seen what looked like a human foot emerging from the ground near a decaying log. Sellers returned to work and informed his boss, who reported the discovery at 1.20pm.

Hae had been buried in a black skirt, white blouse, and stockings, with her legs twisted to the right but her upper body face-down. She lay in a depression which had been further excavated and then covered with debris. The medical examiner could not pinpoint a time of death, but decomposition and scavenging marks suggested she had been there for some time. Since there had been no trace of her since 2.15pm on January 13th, the police hypothesized that she had been killed not long thereafter. There was no evidence of sexual assault, recent sexual activity, or a prolonged struggle. Her autopsy report found evidence of “[b]lunt force injuries to the right back and right side of the head” consistent with impact on a hard surface severe enough to stun.

Hae’s body lay within Baltimore city limits, so the city took over. The discovery was announced on February 11th, 1999, but police withheld information including the cause of death. On February 12th, an anonymous caller reached Baltimore homicide detective Darryl Massey and encouraged police to focus on Adnan Syed, speaking vaguely of plans Adnan might have had to “harm” Hae and dispose of her car in a lake. Other suspects remained on the police radar, particularly Alonzo Sellers. Sellers already had a record of indecency arrests, including stripping in front of a female police officer. He had also walked quite a long way into brushy undergrowth just to urinate.

Yet police could find no link between Sellers and Hae. Besides which, a random sex crime seemed unlikely: there were no signs of recent intercourse or self-defence. And why would Sellers report Hae’s body if he had killed her? Sellers agreed to police interviews and took lie-detector tests without a lawyer present. His first interview was conducted on February 18th, 1999, during which he drew a sketch of where he had found Hae’s body. The first polygraph began at 5.40pm and it indicated deception. But this was ultimately ruled inconclusive because Sellers was distracted and under time pressure. On February 23rd, Coppin State College sent 70 pages of Sellers’s employment records to detectives on the Hae Min Lee murder. Timesheets showed Sellers had worked until 4.00pm (51p) on the 13th. The next day, police asked Sellers for a second polygraph and he agreed. The examiner asked how Hae Min Lee was killed. Sellers said he didn’t know, and this time, the polygraph indicated no deception.

Detectives also considered Hae’s new boyfriend Don. When first contacted by Officer Adcock, at 1.30am January 14th, Clinedinst said he had worked until 6.00pm the previous day. This was subsequently confirmed by timesheet documents provided by LensCrafters, which a later investigation found could not have been retroactively altered. Later on the 14th, sheriffs searched for Hae’s car in the vicinity of Don’s home. Police continued to question him but found no evidence that he had any contact with Hae on or after the 13th. And Don had no obvious motive to kill Hae. Then in his early 20s, he had gone on a few dates with a charming, ebullient 18-year-old co-worker. They had been intimate. Hae’s diary shows she had fallen for Don and they had talked for hours on the night before she had disappeared. Why would he strangle this promising new love interest to death with his bare hands? Susan Simpson, a fervent Adnan supporter whom we will encounter in Part Two, reviewed the evidence and concluded: “Don was not involved in Hae’s murder.”

Some critics now claim police developed “tunnel vision,” prematurely focusing only on Adnan at the expense of other plausible suspects. But as we’ve seen, Alonzo and Don were both properly investigated and ruled out. Meanwhile, questions about Adnan were accumulating. Even before the anonymous February 12th tip, detectives knew that Adnan had just been dumped by his girlfriend, a period when many domestic violence incidents occur. He had also told investigators two different stories about asking Hae for a ride.

Detectives followed up by subpoenaing AT&T for the call logs for Adnan’s cell phone, which arrived on February 17th. The first batch listed the numbers Adnan’s phone had dialled, but not the numbers of incoming calls. Detectives noted that these call logs showed Adnan had not tried to contact Hae after January 13th by phone (he also sent her no emails). All of Hae’s other friends—except Don—had tried to reach her by phone or email.

IV. Jenn and Jay start talking

The AT&T logs disclosed multiple calls on January 13th from Adnan’s phone to the home of Jennifer (“Jenn”) Pusateri. On February 26th, 1999, Baltimore City homicide detectives William Ritz and Gregory MacGillivary set out to interview Jenn. Adnan’s house was nearby, so they interviewed him first in the presence of his father. According to MacGillivary’s notes, “Syed indicated that he knew the victim Hae Min Lee and that she was a friend of his. He also indicated that he had known the victim for several years. On 13 January 1999, he had the occasion to be at school (Woodlawn Senior High), however doesn’t remember the events that occurred in school that day.” So he had no alibi. From that day forward, Adnan would insist that he had no clear memory of what he was doing on the day Hae vanished.

The detectives then drove to Jenn’s home, where they found her leaving in a car. She told detectives her name and accompanied them to the Homicide Division, where she was interviewed. She didn’t reveal much, but she did let slip that Hae had been strangled, a detail the police had not made public. Jenn agreed to meet police again the next afternoon, and she duly reappeared on February 27th with her mother and a lawyer. She gave a full interview, much of which was recorded and transcribed.

Jenn said that in mid-January, possibly the 13th, she had hung out with Jay in the afternoon smoking dope and playing video games with her brother (like many of the teenage witnesses in this case, Jenn was a regular marijuana smoker). She later received a page from an unknown number. When she called back, someone besides Jay answered and said Jay was busy and would return her call when he was ready to be picked up. Jay later paged Jenn, asking her to meet him at Westview Mall. When she drove out to the mall on the evening of the 13th, Adnan and Jay arrived in a car Jenn did not recognize, driven by Adnan. Soon after Jay got into Jenn’s car, he told her that Adnan had strangled Hae. Jay told Jenn that he had then gone with Adnan to Leakin Park, where he had watched Adnan bury Hae’s body. Jay urged Jenn to say nothing about this. She then drove to a dumpster behind Westview Mall and watched Jay throw one (or possibly two) shovels into it. They later returned to Westview so Jay could check there were no prints left on them.

Detectives now knew two crucial facts. First, Jenn knew how Hae had been killed, something she could not have learned from reading media reports of the investigation. Second, Jay was deeply involved in Hae’s disappearance. Jenn told detectives that after she had spoken to them on February 26th, she had called Jay. Jay told her to tell the detectives the truth, then send them to interview him. The detectives lost no time, accosting Jay at 11.30pm on February 27th at his workplace, an adult video store. Jay agreed to talk to police without a lawyer, and in the recorded part of this interview, he told detectives the first of several versions of what happened on January 13th. (The first three of these accounts are compared in a graphic on the Serial website.)

In his first version, recited in the early morning hours of February 28th, Jay told police that Adnan had called him at 10.45am on the morning of the day Hae disappeared. He offered to let Jay use his car and phone while Adnan was at school. For most of the afternoon, Jay hung out with Jenn playing video games and smoking marijuana. At 3.45pm, Adnan called and asked Jay to meet him at Edmonson Avenue in Baltimore. Jay arrived to find Adnan with Hae’s car. Adnan popped the trunk and showed Jay Hae’s body. Adnan and Jay then drove in separate cars to a nearby “Park and Ride” lot near highway I-70, where they left Hae’s car. Jay then dropped Adnan off at Woodlawn for track practice (around 4.30pm) and picked him up again afterward. They went to eat at a McDonald’s, where a cop called Adnan. The pair then collected a pick and shovel from Jay’s grandmother’s house and drove to where they had left Hae’s car near I-70.

With Adnan driving Hae’s car and Jay driving Adnan’s car, they drove to Leakin Park, where Adnan buried Hae. Jay accurately identified the clothes Hae had been wearing when she left school. This was important: Jay was no longer a Woodlawn student, so he would not have had the chance to see Hae leave that day. Jay (in Adnan’s car) and Adnan (in Hae’s car) then drove around looking for a place to dump Hae’s car. After some false starts, Adnan decided on a vacant lot surrounded by rowhouses. Detectives asked Jay where this lot was. He could not recall an address, but said (22p): “It’s like … in the back of a bunch of row homes on like a parking lot … on the west side of Baltimore city.” Detectives asked Jay to ride with them and show them Hae’s car right then, in the early hours of February 28th. Jay led them to a vacant lot near 300 Edgewood Street in Baltimore, where police secured Hae’s 1998 Nissan Sentra.

V. Hae Min Lee’s car

The statements and testimony provided by Jenn and Jay were central to the case against Adnan Syed. Jay had witnessed the aftermath of Hae’s murder and Jenn had witnessed the aftermath of Hae’s burial. They both willingly confessed their involvement to police, and Jay later pled guilty to his role in the disposal of Hae’s body. Bear in mind that when Jenn and Jay first gave police this information, they did not know whether or not Adnan had given investigators an alibi for the afternoon of the January 13th. If Adnan had an alibi, Jay would certainly have been arrested and charged with Hae’s murder. Jenn, at a minimum, would have been charged as an accessory after the fact. Jenn spoke to police in the presence of a lawyer, who doubtless warned her of this. By implicating themselves in the cover-up, Jenn and Jay staked their futures on Adnan’s guilt.

Jay knew where Hae’s car was, which makes it almost impossible to pin the blame on alternate suspects. Assuming Don Clinedinst, Alonzo Sellers, Bilal Ahmed, or some random serial killer murdered Hae, how did Jay know where to find Hae’s car? The only answer is that Jay helped one of these people ditch Hae’s car. But none of these people knew Jay. Adnan’s advocates are therefore forced to reach for other theories to explain Jay’s knowledge of the vehicle’s whereabouts. The least implausible is that Jay came across Hae’s car by chance, perhaps by driving past the lot. There is no evidence of this, and it requires some bold assumptions.

First, Jay must have recognized Hae’s nondescript car parked among other similar cars as he drove by a random vacant lot. Then, he did not tell anyone, even after Hae’s body was found and the car was advertised as key evidence in a murder case. This silence not only hindered a murder investigation of someone Jay knew, it also cost him thousands of dollars. An American organisation called “Crime Stoppers” rewards tipsters who help solve crimes. It’s all anonymous: Crime Stoppers keeps no records and pays tipsters with untraceable cash. So why would Jay, a poor kid who worked minimum-wage jobs, pass up a risk-free, tax-free windfall?

An even less plausible explanation for Jay’s knowledge is a police conspiracy, which would have had to unfold something like this: Cops found Hae’s car at some point and simply left it there. Off the record, they told Jay where the car was, then ordered him to pretend that he was giving this information to the police rather than vice versa when they restarted the recording. According to this theory, Jay may either be the real killer (intent on framing Adnan) or he knew nothing about the crime at all. But why would police leave a car full of evidence in a murder case sitting in an unsecured vacant lot, where it might be stolen or vandalized? Presumably to protect the “real” killer and pin the blame on Adnan. But who was that killer, and why would police want to protect him (or her)?

For that matter, why would they want to frame Adnan instead of Jay? Why not remove all doubt by simply planting incriminating evidence in Hae’s car? It would have been easy to take a drink cup from Adnan’s track practice (or Jay’s work), smear it with Hae’s blood and soil from the burial scene, and drop it in Hae’s car. Like most of the theories offered to exculpate Adnan, the police-conspiracy theory can be sliced to bits by Occam’s Razor—it is backed by no evidence and generates endless unanswerable questions and conundrums.

After Jay’s interview, detectives had ample evidence for an arrest warrant, which they served immediately, arresting Adnan at his home in the early morning hours of February 28th, 1999. They likely suspected Adnan might try to flee if he discovered Jay was cooperating, perhaps using his expired Pakistani passport and the new passport photos police later found in his car. Adnan was booked in at the homicide interview room at 6.30am on Sunday, February 28th. Detectives interviewed Adnan on and off for several hours. He did not ask for a lawyer. The next day, March 1st, 1999, Adnan told his defence lawyer that police pressured him to confess (38p), mocking him for “trusting a black guy who puts pins through his mouth” and suggesting it must “eat you up inside” to remember Hae’s dead face staring up at him from the trunk and a hole in the ground. Nevertheless, he told them nothing of substance.

VI. The State builds its case

Adnan’s first call was not to his parents but to Bilal Ahmed, the man who had helped him obtain a cell phone. Bilal managed to convince Christopher Flohr and Douglas Colbert to represent Adnan, starting immediately. Flohr was a criminal-defence lawyer from New York who had recently relocated to Baltimore. Colbert was (and still is) a professor at the University of Maryland Law School. Both were members of the “Lawyers at Bail” project, which represents suspects at bail hearings. Bilal promised them that the Baltimore Muslim community would raise a collection to pay Adnan’s legal fees, and he started gathering contributions. He even persuaded some supporters to pledge their homes as collateral. Flohr immediately hired well-regarded Baltimore private investigator Drew Davis.

Adnan was denied bail, which is routine in murder cases. A grand jury indicted him for murder and other charges on April 13th, 1999. Detectives obtained a court order forcing AT&T to disclose more information about Adnan’s cell phone, including which cell-phone towers were pinged by his calls. This initial location information was crude, but it helped convince detectives that Jay’s initial story about where he was when he had Adnan’s cell phone didn’t hold water. Detectives brought him back in for further questioning on March 15th, 1999. Jay told them that he agreed to help Adnan bury Hae but didn’t report the crime because Adnan had threatened to expose him as a drug dealer. Further, as a young black man in Baltimore, Jay said he distrusted police because they had hassled him (and his family members) repeatedly, pulling him over for no reason, siccing dogs on him, forcing him to spread-eagle on snow: “I got my ass kicked plenty of times.”

Jay changed his story in this interview and in later interviews, possibly with subtle input from detectives. Adnan’s supporters point to the fact that Jay spoke to detectives for hours off-record, and they maintain that detectives helped Jay tailor his account to other facts. They are likely right about this and correct to be concerned. Detectives, consciously and not, often shape statements and testimony to fit their preferred narrative, and this has contributed to many wrongful convictions. In an ideal world, criminal accomplices would instantly confess everything, as in the denouement of an Agatha Christie novel.

In real life, however, if several people are involved in a crime and one of them offers to talk, detectives must make a judgment call. If they charge everyone with the maximum, everyone will lawyer up. So detectives work to “flip” the accomplice who seems less culpable. This horse-trading strikes many outsiders as ethically questionable, and criminals consider it betrayal (hence the saying “snitches get stitches”). Yet the law allows it so long as the police do not knowingly solicit perjury. Without deals like this, it would be impossible to solve cases in which the only (or best) eyewitnesses to a crime are involved in it. And those happen every day.

Jay still did not have a lawyer. In late summer 1999, prosecutor Kevin Urick decided to charge Jay as an accessory after the fact to Hae’s murder, then offer him a deal for his testimony. Urick sought out a defence lawyer for Jay, which was quite unusual. Prosecutors rarely arrange representation for witnesses in pending criminal cases, instead leaving this task to the court or public defender. Nevertheless, there was nothing improper about Urick’s actions. The lawyer Jay hired on Urick’s recommendation, Anne Benaroya, was a former public defender who was then in private practice. She agreed to represent Jay pro bono.

In a 2015 interview with law professor Colin Miller (a believer in Adnan’s innocence), Benaroya said Urick contacted her because they were both then working on a nightclub-shooting case, and because, Benaroya believes, she had a reputation as a “true believer” who would protect Jay’s interests. Urick did not pressure her, not that it would have had any effect. Asked about Jay’s many story changes, Benaroya said, in Miller’s paraphrase, that this was “completely unsurprising and it’s certainly common for people involved in crimes to change their stories.” Benaroya did admit, however, that Jay’s stories had more inconsistencies than usual.

Benaroya (who now works for an animal-rights organization) nevertheless insisted she found Jay credible and still believes the basics of his story are true. Together, Benaroya and Urick worked out a deal in which Jay agreed to accept a plea bargain calling for a partially suspended five-year sentence. Benaroya signed the agreement on Jay’s behalf on September 2nd, 1999. The parties appeared before Judge Joseph P. McCurdy on September 7th to formalize it. Jay did not officially plead guilty at this time, he only promised to do so later. Urick reserved the right to withdraw the offer if he wasn’t satisfied with Jay’s testimony. He was, and Jay duly pled guilty on July 6th, 2000. He did not serve any jail time, but now has a felony conviction on his record.

Forensic reports trickled in during the spring and summer of 1999. A red fibre was found in Hae’s hair, which was consistent with Jay’s claim (on February 28th) that Adnan had been wearing red gloves (13p) on the afternoon of January 13th. Adnan’s fingerprints (17p) were found on a piece of “floral paper” (presumably the type of paper used to wrap flowers in) in the trunk of Hae’s car. On May 1st, 1998, Adnan had presented Hae with a single rose in front of a classroom of students. Adnan’s left palm print (15p) was found on the back cover of a map book of Baltimore. The page showing Leakin Park had been torn out. Jay testified that Adnan told him Hae had kicked and broken a lever on the right-hand side of the steering wheel during the brief struggle in Hae’s car. Strangulation often induces involuntary muscle spasms due to oxygen deprivation, such as in the George Floyd case. The lever was in fact dangling limply in police footage of Hae’s car, although forensic reports concluded that its housing had not been broken. A lot of this evidence was suggestive but hardly conclusive, since Adnan had often been in Hae’s car.

The cell tower “ping” location evidence was more revealing. Prosecutors asked AT&T to provide an expert on cell-phone location evidence, and AT&T nominated Abe Waranowitz, an “RF” (radio frequency) engineer who had designed the West Baltimore cell-phone network on AT&T’s behalf. Using cell-tower location data, Waranowitz plotted the approximate location of Adnan’s phone during January 13th. He even conducted (23p) a “drive test,” retracing Jay and Adnan’s movements and recording which cell towers would have been pinged at which locations. The results were consistent with the second part of Jay’s story.

VII. A well-funded defence prepares for trial

Many wrongful convictions are due to overworked, underfunded defence lawyers who cannot or do not properly prepare for trial. Not here. Within hours of his arrest, Adnan Syed had multiple lawyers by his side, assisted by investigators, paralegals, and law students. That remained the case until well after his conviction. The sizable fees were paid partly by Adnan’s family, and partly by the local Muslim community. Drew Davis, the defence investigator, met personally with Adnan on March 3rd, 1999, just days after his arrest. Based on what Adnan and other witnesses had told him, Davis began driving around Baltimore and Maryland, talking to witnesses and scouting locations. He managed to interview many witnesses before detectives did.

Adnan would need a trial lawyer. Flohr suggested Cristina Gutierrez. One of 10 children born to working-class parents, Gutierrez had worked her way through law school and become a fierce advocate for criminal defendants. She had won several high-profile cases, received numerous awards, and become the first Latina to argue before the US Supreme Court. She was regarded as one of the best criminal-defence attorneys in Baltimore, if not the best. As the later harsh scrutiny of her career revealed, Gutierrez also had chronic medical problems, including multiple sclerosis and diabetes, and she took on too many cases. In late 1999 and 2000, she began ignoring some of her clients, missing appointments, and failing to follow through on promises.

She became severely ill in late 2000, well after Syed’s conviction. By that time, she was the subject of almost 30 official complaints, many of which were ruled well-founded. Gutierrez was eventually disbarred with her own consent in May 2001 and died in 2004 at the age of 52. The documentaries about Adnan’s case dwell on these facts. However, aside from a few anecdotes, there is no evidence that her illness affected Adnan’s defence. In 2019, Adnan’s trial judge, Wanda Heard, swore in an affidavit that Gutierrez’s performance had been competent and even aggressive, and that Adnan was convicted based on the evidence, not any error on Gutierrez’s part.

In any event, Gutierrez was far from alone in preparing for Adnan’s trial. Her law partner Mark Martin visited Adnan, as did other staff from her firm. Christopher Flohr continued to visit Adnan even after Gutierrez had taken over. But Adnan’s lack of an alibi presented Gutierrez with a serious problem. In an early interview, Adnan had told Flohr that he and someone named “Dion” checked a noise Adnan’s car was making between 15:00 to 15:30 “in front of school. Front entrance to gym.” Dion’s name did not come up again. In July 1999, Adnan briefly mentioned Asia McClain to his defence team as a possible alibi, but this is the only mention of her name in the defence files.

By the time of Adnan’s first trial in the fall of 1999, he had apparently decided that his best option was to stick with what he had told detectives on February 26th: He remembered nothing specific about the afternoon of January 13th. It must have been, as he would later insist, a normal school day like any other. Maryland law requires the defence to notify the prosecution of any alibi, so the prosecution can investigate it. Gutierrez sent this notice of alibi to prosecutor Kevin Urick on October 4th, 1999:

On January 13, 1999, Adnan Masud Syed attended Woodlawn High School for the duration of the school day. At the conclusion of the school day, the defendant remained at the high school until the beginning of his track practice. After track practice, Adnan Syed went home and remained there until attending services at his mosque that evening. These witnesses will testify to [sic] as to the defendant’s regular attendance at school, track practice and the Mosque; and that his absence on January 13, 1999 would have been noticed.

The notice then listed the names and addresses of about 80 persons, some of whom were members of Adnan’s track team, but most of whom were mosque members.

Timing is important here. Since March 1st, 1999, Adnan Syed had been represented by three experienced (and expensive) criminal-defence lawyers. According to Adnan’s visitor’s logs covering the time between his arrest and September 21st, 1999, Adnan had 19 lawyer visits, including seven meetings with Gutierrez. He was also visited by other team members (paralegals, clerks, and law students) nine times, twice accompanied by Gutierrez. One of Baltimore’s best private investigators had been on the case for months. And after all this research and consultation, Gutierrez provided official notice that Adnan could present up to 80 witnesses to testify he went to school, attended track practice, and attended mosque beginning at 8.00pm. Not one of these witnesses testified at trial except Adnan’s father.

Adnan’s supporters dismiss the alibi notice, blaming Gutierrez for failing to properly vet the list or craft a more plausible alibi. The fault, however, lies squarely with Adnan Syed. It is inconceivable that he did not know of and approve this move.

VIII. Adnan Syed tries to plead guilty and declines to testify

Yet just as he was preparing to go to trial with 80 alibi witnesses, Adnan was pleading with Gutierrez to secure a deal which would have put him in prison for decades. At least that was what he testified (19p) during a 2012 appeal hearing, claiming he had asked Gutierrez, in late 1999, whether she could “speak to the State’s Attorney or request some type of a plea. And I explained to her that I didn’t really have confidence that I’d be able to prove I was somewhere else when … the murder took place, from the information that we were getting.” This 2012 hearing was the first time Adnan had ever claimed that he wanted to plead guilty. There is no mention of his request for a plea in the defence file.

Adnan’s claim that he wanted to plead guilty in 1999 raises troubling questions. Why was he convinced that he couldn’t prove his whereabouts when his lawyer was identifying 80 witnesses who she said could do just that? Why would Adnan agree to serve decades in prison for a crime he didn’t commit? How would Adnan’s plea strike the members of the Baltimore Muslim community who had financed his defence? In the 2012 hearing, Adnan also testified that he had two alibi letters from a fellow student named Asia McClain. Asia, he explained, was prepared to testify that she had spoken to him in a library near the school campus after class, and Adnan now revealed that he’d had her letters since March 1999. So why was he suddenly so pessimistic? Serial mentions Asia McClain 72 times but never mentions the 80-name alibi list. Not even during this lament from host Sarah Koenig (22p): “Why, oh, why was [Asia] never heard from at trial—a solid, non-crazy, detail-oriented alibi witness in a case that so sorely needed alibi witnesses?”

Another problem for Gutierrez was that Adnan did not take the stand. Accused of murder by an eyewitness, his freedom on the line, knowing the jury was desperate to hear from him, he elected to remain silent. This was Adnan’s decision; American law gives defendants an absolute right to testify in their own defence regardless of their lawyers’ advice. Defence lawyers routinely offer a litany of reasons why even innocent defendants might decline to testify: Previous convictions might be disclosed during cross-examination, or the defendant may make a poor impression even when being truthful. But Adnan had a clean record and was universally regarded as engaging and articulate.

Although judges caution juries that a defendant’s decision not to testify should not be inferred as evidence of guilt, a juror might understandably expect an innocent defendant in Adnan’s position to take the stand. Indeed, a juror interviewed for the Serial podcast confirmed that the jury was disappointed when he did not (192p). The decision about whether or not to testify is a momentous one, and only taken after long consultation. The key question is almost always whether the defendant’s story will stand up under cross-examination.

Gutierrez, who had made this judgment call hundreds of times, must have known that Adnan’s story would not. He did not testify for the reason most defendants don’t testify—he had no innocent explanation for his actions. He still does not have one, which is why people still spend hours trying to reconstruct the movements and motives of a man who could clear everything up anytime he wishes.

IX. The prosecution’s case at trial

Adnan Syed’s case went to trial on December 8th, 1999. On the sixth day of proceedings, December 15th, Judge William Quarles declared a mistrial. Quarles had called Gutierrez a “liar” in court during a heated dispute, an accusation heard by the jury. This occurred after most of the State’s case had already been presented, but before the defence’s case had begun. Gutierrez therefore had the advantage of hearing most of the State’s case before the second trial began in February 2000. A new judge, Wanda Heard, Associate Judge for Baltimore City Circuit Court presided. During the second trial, most of the witnesses who had testified at the previous trial gave roughly similar testimony.

As Jay took the stand, Adnan called him “pathetic,” a remark which the prosecution ensured found its way into the official trial record. Jay testified that he had received a call from Adnan at 10.45am on the morning of January 13th, 1999. Adnan arrived at Jay’s house. They went to Security Square Mall for slightly over an hour. On their way there, Adnan told Jay that he was planning to kill Hae. Just after 1.00pm, Jay dropped Adnan off at school, and left with Adnan’s car and cell phone. Jay then went to Jennifer’s house, but she wasn’t there, so he played video games for a while with her brother. While he was at Jenn’s house, he received a call from Adnan at 3.45pm asking to be picked up (this is important). At around 3.55pm, Jay met Adnan at Best Buy, where Adnan showed him Hae’s body in the trunk of her car. Adnan and Jay left Hae’s car at the I-70 Park & Ride.

At around 4.30pm, Adnan called Nisha Tanna, a girl Adnan was interested in. Although Jay did not know Nisha, Adnan gave his phone to Jay to say hello to her. Jay dropped Adnan off at track practice after 5.00pm. Just after 6.00pm, Jay picked Adnan up and they visited Jay’s friend Kristi Vincent. During this visit, Adnan received two calls—the first from Hae’s brother and the second from a police officer. Adnan was noticeably disturbed by this second call, and decided that he and Jay needed to bury Hae’s body immediately. They drove away, picked up shovels from where Jay was living, retrieved Hae’s car, and drove to Leakin Park, where Adnan buried the body. They then left Hae’s car in the vacant lot. Adnan’s cell phone had received two incoming “pings” from a cell tower antenna which covered Leakin Park at 7.08pm and 7.16pm. These “Leakin Park pings” remain a critical part of the case.

Consulting Jay’s prior statements, Gutierrez cross-examined him for five days. She pointed out dozens of inconsistencies and elicited an admission that he had lied repeatedly. Jay’s trial testimony conflicted with his prior police interviews, and with the testimony of other witnesses, including Jenn. Jay explained the reasons for his story changes as best he could, remaining respectful throughout. He made a good impression on the jury (seven of whom were African-American). In Serial, juror Stella Armstrong described (171p) Jay as “streetwise” and someone “who was able to take care of himself … that friend if you got in trouble you would call.” Armstrong summed up her view (173p) as follows: “The defense attorney … basically she was trying to show that Jay killed her, and was blaming it on Adnan. … Nothing led us to believe that he had a motive to kill Miss Lee. That really stayed with me because she was so adamant that he was a liar.”

The prosecution knew Jay was vulnerable, so they presented corroboration. Jenn’s testimony largely tracked her police statements: Jay had told her that Adnan had strangled Hae to death and described his role in helping Adnan dispose of the body. Jay’s testimony was also buttressed by Kristi Vincent, a friend of Jay’s who did not know (3p) Adnan. Kristi testified that Jay had shown up at her apartment with Adnan shortly after 6.00pm on the 13th. Adnan sat (3p) “slumped over” on some pillows, asked her “how to get rid of a high,” and was acting “really crazy” and “real shady.” Adnan got a call and said, “They’re going to come talk to me. They’re going to, you know, what should I say, what should I do?” She then testified that “Adnan just jumped up and left the apartment.” Adnan’s cell phone pings were consistent with his presence at Kristi’s apartment.

Nisha testified that she had received a call from Adnan. This is the “Nisha Call,” which Serial host Sarah Koenig maintained is so important that it should be capitalised. Adnan had met Nisha at a New Year’s Eve party ushering in 1999. She testified that one day shortly after Adnan had gotten his new phone, Adnan called her and then gave the phone to Jay to say hello. Jay didn’t know Nisha, didn’t know why Adnan had given him the phone, and didn’t seem particularly friendly. Nisha was shown Adnan’s phone records and identified an outgoing phone call from Adnan’s phone to her private landline placed at 3.32pm on January 13th, 1999. The call lasted two minutes and 22 seconds. Nisha said that there was no answering machine on her private landline phone.

This testimony corroborated Jay’s statement to detectives that Adnan had called a “girl in Silver Spring” Maryland on the afternoon of the 13th and that Adnan had put Jay on the phone with her. At that time, detectives did not even know who Nisha was, nor that she lived in Silver Spring (which she did). As we will see, the Nisha Call was corroborated by other sources, including Adnan’s own family members. Besides corroborating Jay, the Nisha Call conflicted with Adnan’s alibi. It originated from the area covered by cell-tower antenna L651C, which does not include Woodlawn High School. The Nisha Call thus shows Adnan was (1) with Jay and (2) not on the campus of Woodlawn as he claimed during the crucial period (14:15–16:00) when Hae disappeared.

The first trial had ended before Abe Waranowitz took the stand. Waranowitz was the radio-frequency engineer who had designed the West Baltimore cell-phone network on behalf of his employer, AT&T. Using cell-tower location data, he plotted the approximate location of Adnan’s cell phone during the 13th. Cell-phone towers (now as then) have three antennas dividing a 360-degree circle into three roughly equal 120-degree slices. Each tower has a four-character code, and the three antennas are labelled A, B, and C. This makes it possible to determine the approximate location in which a cell-phone call has been placed or received—somewhere within the 120-degree “slice” of the tower antenna, and within its range of about two miles. Even more crucially, tower pings can be used to determine where a cell phone was almost certainly not during specific calls. Waranowitz’s location data mostly conflicted with Jay’s testimony before about 5.00pm, but largely matched it later.

The State presented its closing arguments on Friday, February 25th, 2000. Prosecutor Kathleen Murphy told the jury (8p) that Hae “was dead in 20 to 25 minutes from when she left school.” This claim has since become a major point of contention in Adnan’s case. Why did Murphy decide to argue that Hae had been killed that early? First, because Hae missed her appointment to pick up her cousin at 3.00pm, suggesting she had been intercepted (at a minimum) by that time. Second, there was an incoming call to Adnan’s cell phone (which was with Jay) at 2.36pm. This could have been Adnan’s “come and get me call.” The prosecution argued that the call probably came from a payphone at the nearby Best Buy store where Adnan went to have sex with Hae and get high.

In retrospect, saying the 2.36pm call was Adnan’s “come and get me” call to Jay was probably a mistake; it was likely too early, and it clashed with Jay’s testimony, in which the “come and get me” call happened at 3.45pm. The prosecution’s tight timeline, and the narrow window in which they claimed the murder occurred, has been seized upon by Adnan and his supporters. They now claim that Adnan can be exonerated if it was not possible to drive from Woodlawn to Best Buy (and kill Hae) within 21 minutes. American juries are, however, instructed that the arguments of lawyers are not evidence, but rather summaries and analysis to help them process the hours of testimony they have heard.

Further, nobody knew precisely when Hae left campus. Teacher Inez Butler, for instance, claimed she saw Hae leave campus around 2.15pm to 2.20pm. However, Butler also testified that Hae was supposed to attend a wrestling match later the same day. Subsequent investigation revealed that the match was not on that date. In both of her police interviews, Adnan’s and Hae’s friend Debbie Warren said she had seen Hae alone in the gym around 3.00pm, although neither the prosecution nor the defence made a big deal about this when it came up at trial (2p), each for their own (different) reasons.

Murphy and Urick likely thought the timing was not a major factor. The murder was probably committed sometime between 2.15pm and 4.00pm, and we will probably never know when exactly. Nobody remembered seeing Hae’s car leave campus on the 13th; nobody had any reason to do so. To knit the evidence into a story for the jury, the prosecution chose a story which fit most of the circumstances, but not all, because the evidence was incomplete and conflicting. Jay was also a factor: The prosecution did not want the jury to think that Jay might have been present when Hae was killed. So the earlier they placed her death, the better. The prosecutors did what trial lawyers do: they made the best argument possible based on incomplete and inconsistent evidence. It worked at trial but nearly cost them the case on appeal.

X. The defence case

The defence faced daunting challenges of its own, including Adnan’s decision not to testify and that his 80 alibi witnesses did not materialize. The only alibi witness was Adnan’s father, Syed Rahman. During Gutierrez’s direct examination, Rahman said Adnan was at the mosque on the 14th, when Adnan led a prayer session, an event Rahman described (12p) as “the happiest occasion of my life.” Rahman did not testify that Adnan was at the mosque on the 13th. The prosecution cross-examined Rahman briefly, ignoring the issue of dates. Only on re-direct examination did Gutierrez ask Rahman to confirm (14p) that Adnan was at the mosque on the 13th (my emphasis):

Q: And so, he went with you on the 14th and you specifically recollect an additional fact about that day right?

A: That’s right.

Q: That he led the prayers that day, right?

A: That’s right.

Q: He also went with you on the 15th?…

A: Yeah.

Q: And he also went with you on the 13th?

A: That’s correct.

This was the only alibi evidence presented by the defence, and it did not account for any time before 8.00pm. Further, the prosecution had already placed Adnan’s phone at locations away from the mosque between 8.00pm and 10.00pm. But nobody was in a hurry to put Adnan’s father on the spot. Criminal lawyers understand the painful dilemmas faced by family members of defendants who ask their loved ones for alibis.

To try to defuse the Nisha Call, Gutierrez called Saad Chaudry to testify. Saad was Adnan’s best friend and he owned a phone similar to Adnan’s. He testified that if Nisha’s number was in the list of recent calls, Jay might have dialled it accidentally. But Saad could not explain why, if Jay had accidentally called a stranger, he had spoken to her for two minutes and 22 seconds. On cross-examination, Kevin Urick got Saad to admit (40–41p) that he had not seen Adnan on January 13th, and that Adnan had said he and Hae often had sex in the Best Buy parking lot just after school. Gutierrez also called Debbie Warren, who testified that she never considered Adnan threatening, but also detailed Adnan’s possessiveness. Gutierrez called Woodlawn track coach Michael Sye, who testified that Adnan generally came to track practice but could not confirm if he was there on the 13th.

Prosecutors delivered crisp closing arguments (including the short timeline). They stressed Adnan’s lies about asking Hae for a ride; they reminded the jury that Adnan had scrawled “I’m going to kill” on the back of Hae’s letter breaking up with him; they emphasized the importance of the Nisha Call, the Leakin Park pings, and the unchanging “spine” of Jay’s story (that he saw Hae’s body and helped Adnan bury her), which remained consistent throughout all versions. American prosecutors (unlike their British counterparts) are not allowed to mention that the defendant did not testify, and they did not do so in Adnan’s trial.

Gutierrez’s closing arguments, on the other hand, were often rambling, probably because she had so little to work with. Yet the main points emerged: Detectives singled out Adnan too soon and failed to properly vet other suspects—especially Alonzo Sellers, who had supposedly fought through 120 feet of Leakin Park underbrush just to urinate. The cell-phone testimony was novel and potentially unreliable. Jay had lied repeatedly, changing his story to please detectives and prosecutors, who held the whip hand. The Nisha Call could have been accidental, despite Nisha’s testimony that she had spoken to both Adnan and (briefly) Jay. Gutierrez also suggested (26p) that Jay murdered Hae. Perhaps Hae “stopped Jay Wilds in her very good friend’s car and then something happened—and that it really didn’t cause any other injury—anything else is pure speculation.”

The jury deliberated for just two hours, then convicted Adnan Syed on all counts. Fourteen years later, Serial contacted (176–77p) six jurors and reported that, “[N]one of them had any lingering doubts about the case. None of them wondered if the investigation was shoddy. None of them were much bothered by how Jay’s statements to police had shifted over time.” The Baltimore Korean community, which had been following the case from day one, was reassured.

Adnan was sentenced in a hearing on June 6th, 2000. Through an interpreter, Hae’s mother said:

In Korean proverb there is a saying that parents die, they bury in the ground, but when children die, they bury in their hearts. … The day in 1999, the day she disappeared, she always hoped she would appear, and she was always outside looking for her and always wondering where she could be, and she was desperate and hopeful that, she will appear. … I came to America because she was such a nice daughter, and in order to give her a future, we came to America so that she could have a decent education and a decent future. When I die, when I die my daughter will die with me. As long as I live, my daughter is buried in my heart. I don’t know where to hear her voice. I don’t know where to touch her hand… (Sobbing)

Adnan told the court that he had claimed innocence “from the beginning” and did not “know why people have said the things they have said that I have done or that they have done.” Judge Heard was unimpressed. In her summary, she said:

This wasn’t a crime of passion. … That means you thought about it. The evidence was, there was a plan, and you used that intellect. You used that physical strength. You used that charismatic ability of yours[.] You used that to manipulate people. And even today, I think you continue to manipulate even those that love you, as you did to the victim. You manipulated her to go with you to her death.

Heard then sentenced Adnan Syed to life in prison for murder in the first degree and lesser sentences on the remaining counts, amounting to life plus 30 years. By international standards, this sentence is extreme for a 17-year-old, even for premeditated murder. In fact, it would have seemed extreme during many other eras of American history. Yet it raised few eyebrows in 2000. Beginning in the mid-1960s, the homicide rate in the US had more than tripled, reaching a peak in the early 1990s. Baltimore’s homicide rate was four times the national average, making it one of the most dangerous cities on Earth. Crime-weary voters had significantly toughened sentencing laws, and judges were not immune to the national mood.

Adnan Syed adjusted well to prison. Over subsequent years, he operated an illicit business, acquired an illegal cell phone, and even married a woman named Kanda, whom he presented with a $10,000 dowry (the marriage didn’t last). None of this is particularly damning. Maryland’s prisons were notoriously lax at that time, and any enterprising convict would have followed Adnan’s path. In all other respects, Adnan was a model prisoner. He caused no problems, took courses, helped his fellow inmates, earned awards, and became a hafiz (a person who has memorized the Koran). He was just one of thousands of anonymous lifers. The word “podcast” was still unfamiliar, and the idea that Adnan Syed’s name would one day be known to millions across the globe would have seemed preposterous. Yet that is precisely what happened.

Correction: Due to an editorial error, an earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Adnan Syed was 17 when he was convicted. Apologies for the error.