Words Are the Only Victors

Salman Rushdie’s new novel is a powerful reminder of his vital role in the endless battle for free speech.

Salman Rushdie found his voice in 1975. His first novel, Grimus, published earlier that year, had been ignored by the public and derided by the critics. At the same time, Rushdie was watching younger contemporaries such as Ian McEwan and Martin Amis cement their places among the British literary elite, while he remained saddled with his day job as an advertising copywriter.

Despite these setbacks, Rushdie still felt that he had a fresh, authentic literary voice to discover. He travelled back to his native India in search of it, knowing only that he wanted “to write a novel of childhood.” It was on this trip that he began to conceive Midnight’s Children, a novel he would write against the tradition of British literature set in India. While he admired some of these classic works, such as E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India, he took issue with the voice. The British style was cool and collected. The India that Rushdie knew was anything but. It was hot and “noisy and vulgar and crowded and sensual.” And it needed a voice to reflect that.

It was this unique migrant’s voice that catapulted Rushdie to literary stardom. His narrator in Midnight’s Children was loud and frenetic, reflecting not only the energy of a post-independence India, but also the magic-realist style that would become a trademark of his fiction.

The novel succeeded beyond any realistic expectations. It was a hit with both the public and the critics, becoming an international bestseller and winning the UK’s most prestigious literary award, the Booker Prize. When a special award was given a few years later to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the prize, it was Rushdie’s book that was selected as the “Booker of Bookers.” And when a similar award was given again for the 40th anniversary, it was Rushdie who received the accolade once more.

Midnight’s Children signalled the emergence of a new literary voice, which has been a constant presence over the last 40 years, shifting and evolving across 14 novels, a memoir, and several collections of essays and short stories.

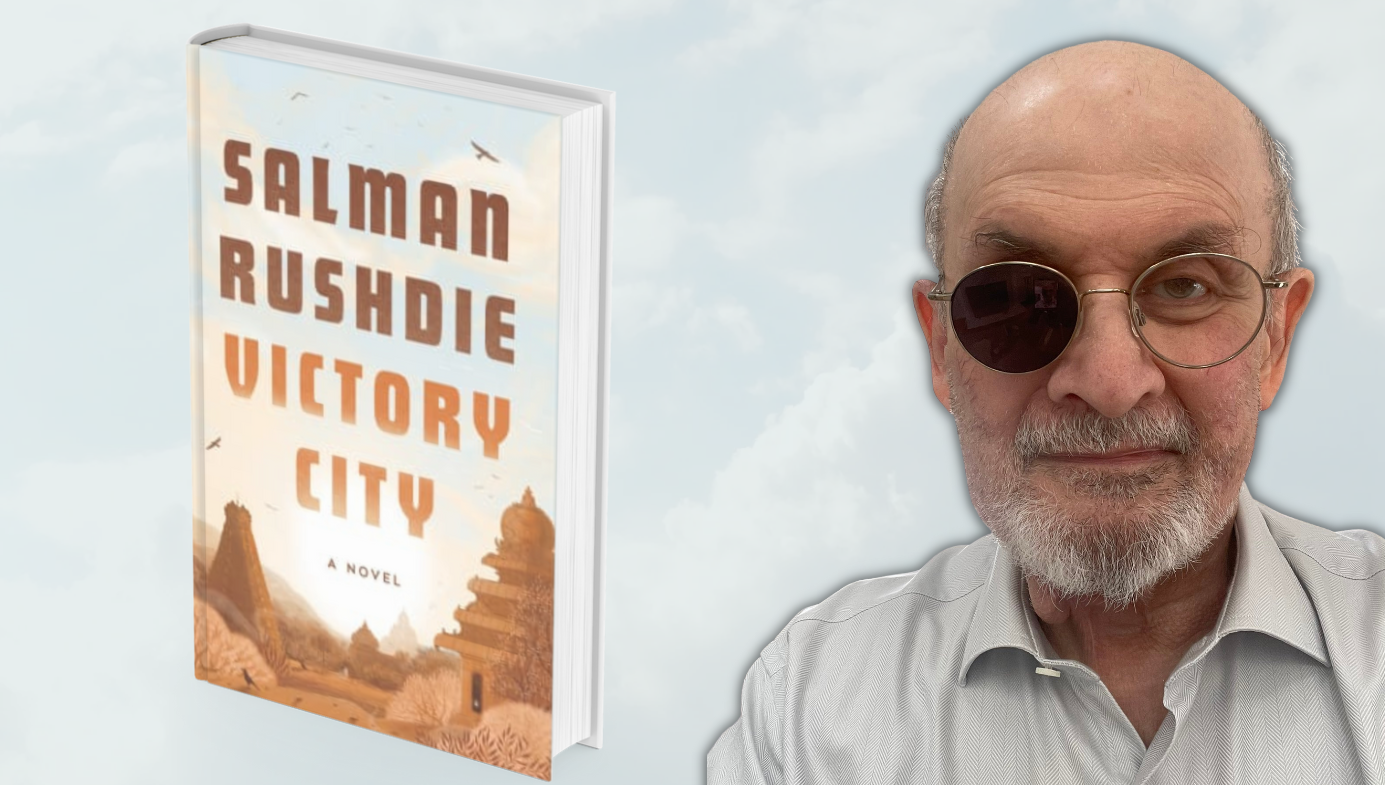

The latest iteration of Rushdie’s literary voice is published this month in Victory City, his 15th novel. While the story sees Rushdie return to his native India once more, the voice is more detached and pseudo-academic this time, reflecting the novel’s conceit that the text is “a translation of an ancient epic.” Nonetheless, many of Rushdie’s trademarks are there—the blending of the historical with the magical, the pointed reminders of the narrative’s unreliability, and the pithy humour, which is presented here through a series of italicised asides from the “translator.”

While Rushdie’s new novel, which charts the rise and fall of the titular city across the 14th to 16th centuries, may seem far from contemporary affairs, it will undoubtedly be read within the context of recent events in Rushdie’s life.

On August 12th, 2022, Rushdie was attacked onstage, just as he was beginning to give a public interview at the Chautauqua Institution in New York state. He was stabbed multiple times, leaving him with serious injuries, including the loss of sight in one eye and loss of use of one hand. Since the attack, the usually gregarious Rushdie has not appeared in public.

While this event was an enormous shock to the literary community and the wider world, Rushdie had been living under the threat of violence for decades. This danger stemmed from a controversy around his fourth novel, The Satanic Verses, published in 1988.

In one chapter of the novel, Rushdie had presented a dream sequence based on a contested event in the life of the prophet Muhammad, in which Satan convinces him to accept three pagan goddesses. Another chapter had waded into equally controversial territory, with a depiction of a brothel whose prostitutes share the same names as Muhammad’s wives.

These elements ignited significant anger among some members of the Muslim community, despite the fact that few of them had read the book. Indeed, on its release, an “apocryphal Page 15 Club” was joked about among readers of The Satanic Verses, comprising those “who could not get past that point in the book” because of its dense and challenging literary style.

Nonetheless, “The Satanic Verses” sparked international protests. It was banned in several countries. Book burnings took place on the streets of British cities. And the Ayatollah Khomeini, supreme leader of Iran, issued a fatwa, calling on Muslims to assassinate Rushdie, forcing him into hiding for a decade.

Even with Rushdie in hiding the controversy continued to rage. Bookstores in the United States were firebombed. The novel’s Japanese translator was stabbed to death. And dozens were killed in anti-Rushdie protests around the world.

But as the years passed the controversy waned and Rushdie began to appear more frequently in public. By the time of the Chautauqua event, more than 33 years had passed since the fatwa, which was beginning to seem like an empty threat. Perhaps this explains the lack of security at the event, where audience members were prohibited from bringing coffee into the hall but were seemingly not checked for weapons.

While Rushdie had completed and submitted Victory City to his publishers months before the Chautauqua event, it will inevitably be read in the shadow of that attack—and in the context of the long battle Rushdie has been fighting ever since The Satanic Verses was published. But this reading is apt given that the novel’s subject and themes happen to connect so serendipitously with the central issue of the controversy: free speech and the power of words.

In Victory City, the protagonist, Pampa Kampana, is defined by the power of her words. She begins the novel as an ordinary young girl. But when she is endowed with the abilities of a goddess, she causes a new city to sprout from the earth and lives an elongated lifespan to match the 250 years between the city’s rise and fall. At the city’s genesis, Pampa isolates herself for days, writing fictional backstories which she whispers into the ears of its newly materialised inhabitants, imbuing them with memories and history and culture. Towards the end of the novel, Pampa suffers a violent attack intended to silence her, which damages her eyesight. But she persists, writing an epic poem to chronicle the full history of the city, which outlasts everything else.

This focus on the power of words, and the extraordinary mirroring of life and fiction through the violent blinding of the authorial figure of Pampa, position this latest novel as a remarkable rebuttal to Rushdie’s attackers and attempted silencers. And it is these beginning and ending sequences which are the most engaging.

The first few chapters, which were published in an adapted form in the New Yorker as “A Sackful of Seeds” in December 2022, display Rushdie’s mastery of magical world building. The founding of the city, which is grown from a bag of magical seeds, effectively foreshadows both the success and failure of Pampa’s aim to build a utopian community based on principles of equality. The brothers whom Pampa selects to lead the new city agree at first to the principle of religious freedom—they say that they “don’t really care” if some men are circumcised and others are not. But soon they clash over concubines and threats of violence over which one should be king.

When the city eventually does fall, Rushdie brilliantly captures the fear and dread of a civilisation in collapse. Readers have known this was coming since the first paragraph of the novel, and the inevitability of the destruction makes the futile reactions of the citizenry more poignant—some attempt to flee, while some stand and fight despite being outnumbered 20,000 to one. The only act that seems purposeful in the face of this inescapable violence is Pampa’s. She remains to die with the city, recording its final moments in writing and burying her words in a clay pot beneath the earth. It’s an ending that powerfully reflects Rushdie’s central idea of the immortality of words, as the city, whose entire history we have followed, is destroyed and all that is left is the book of its telling.

If Rushdie’s new novel has a flaw, it’s that the middle chapters do not equal the power and intrigue of the beginning and ending. Indeed, when Rushdie has Pampa declare “if the middle is unnaturally prolonged then the story is no longer a pleasure” one cannot help feeling that he is commenting on his own novel.

Rushdie is known for the depth of research he puts into his fiction, and Victory City seems to have been a particularly scholarly undertaking, with more than a dozen books on Indian history cited in his acknowledgments. But Rushdie sometimes becomes mired in this historical detail. The magical elements of the novel seem to emerge and disappear whenever they are convenient to move the story from historical point A to historical point B. Likewise, in hitching his story to 250-year history of Vijayanagara (the real historical location on which Rushdie’s magical city is based) Rushdie is forced to introduce and discard new characters as the generations pass, allowing little opportunity for development.

Furthermore, Rushdie’s use of the historical to comment on present affairs feels equally underdeveloped. The press release describes Victory City as “a magical realist feminist tale” and Pampa’s central quest in the novel is for “men [to] start considering women in new ways.” The sentiment is worthy enough, but Rushdie does not offer us anything other than the usual platitudes, such as the point that women can be “as good at everything as men.”

However, paradoxically, these criticisms are also tied to Rushdie’s greatest virtue as a writer, which is that he has always written for himself. Readers may not necessarily be fascinated with medieval Indian history, but Rushdie chooses to write about it because it interests him. Likewise, some may quibble at the insertion of modern progressive talking points in a historical novel, but Rushdie includes these as part of a complex tapestry that represents his own personal politics, not to score easy points.

The ability to write purely for oneself may be a kind of narcissism, but it is also perhaps the most important virtue for the writer. It unlocks the freedom and individuality necessary to truly break new artistic ground, as Rushdie did with his migrant’s voice in Midnight’s Children. Once a hypothetical reader slips into the mind of the writer, timidity and censoriousness can appear—especially in an age where we are primed for hypervigilance to offence.

Rushdie has always been steadfast in his ability to write the books that he himself would want to read. Indeed, he seems to have adopted as his credo the motto of Popeye—“I yam what I yam”—which adorns his Twitter bio and is also quoted in his 1995 novel The Moor’s Last Sigh. He has stated in recent interviews that one of things he is most proud of is that he never succumbed to writing “revenge books” while living under the fatwa. Rather, he remained “the writer that [I] want to be.” In one of his more recent novels, Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights, he even delved into the subject of Islamic theology again, adding a defiant epigraph (quoting Italo Calvino) for any who might warn him away from such dangerous topics: “Instead of making myself write the book I ought to write, the novel that was expected of me, I conjured up the book I myself would have liked to read.”

Similarly, in his public life, Rushdie has always said what he thought and stood up for what he believed. Living under the threat of assassination from a foreign head of state, one could easily be expected to kowtow or disappear into silence. But Rushdie has spoken out, not letting those who called for his death get away with it—from Cat Stevens, the singer-songwriter who said that if Rushdie turned up on his doorstep “I’d try to phone the Ayatollah Khomeini and tell him exactly where this man is”; to the British government, which recommended Iqbal Sacranie, who served on the Muslim Council of Britain, for a knighthood (which he received), despite his assertion that “Death, perhaps, is a bit too easy for [Rushdie].”

Rushdie’s public statements and activism have gone beyond his own case as well, and he has transformed himself into one of our most important advocates for free speech. In 2015, Rushdie was damning in his response to six authors who objected to PEN America, a free speech organisation, presenting an award to the French magazine Charlie Hebdo, after 12 people were killed by Islamic extremists who were offended by cartoons published in the magazine. Peter Carey, one of the six authors, stated that he objected to “PEN’s seeming blindness to the cultural arrogance of the French nation, which does not recognise its moral obligation to a large and disempowered segment of their population.” Rushdie’s response was scathing: “If PEN as a free speech organisation can’t defend and celebrate people who have been murdered for drawing pictures, then frankly the organisation is not worth the name.” Of the objecting authors, he added: “I hope nobody ever comes after them.”

Rushdie loathes to be defined by the fatwa. “All I want is to be seen as someone who writes books,” he said in a 2008 interview when asked about it. But, as his narrator in Midnight’s Children observed: “I am the sum total of everything that went before me, of all I have been seen done, of everything done-to-me.” Thus, Rushdie’s identity is inevitably wrapped up in both what he has “done” (his writings) as well as what has been “done to him” (the fatwa).

But Rushdie’s increasing weariness with the “albatross around my neck” does him a disservice. Because we do not remember him just for what was “done to him,” but for how he has responded. Indeed, just as Rushdie found his literary voice in 1975 as he was writing Midnight’s Children, he has found an equally vital public voice as a free speech advocate in the years and decades since the fatwa was issued.

The appearance of Victory City in the aftermath of the attack on Rushdie is a powerful celebration of these two voices, and a reminder that the battle for free speech is endless. Just as Pampa is attacked in 16th century India to silence her, Rushdie is attacked today. And just as similar characters reappear across the generations in Rushdie’s magical city, his own story has echoes in history. A generation ago, Egyptian writer Naguib Mahfouz was similarly condemned for a novel deemed blasphemous. Like Rushdie, he was finally victim to a stabbing attack some 30 years after the initial controversy. And, like Rushdie, he survived, but was left with permanent damage to his eyesight and his arm.

The victorious title of Rushdie’s novel seems to declare that even amidst all the attempts to use violence to silence dissent and controversy, words will always outlive tyrants. As the novelist Colum McCann recently stated: “He is saying something quite profound in ‘Victory City.’ He’s saying, ‘You will never take the fundamental act of storytelling away from people.’ In the face of danger, even in the face of death, he manages to say that storytelling is one currency we all have.”

In this way, Victory City is a message of defiance. No act of violence can erase the words and ideas Rushdie or any creator has produced. To drive this message home, the author recently reappeared in the public sphere, with an interview in the New Yorker in early February. Accompanying the article there is a photo of Rushdie—the first since the attack. He stares directly at the viewer, his scars visible, in defiance at his attacker and all those who have called for his death. The right lens of his glasses is blackened, covering the eye which was blinded, but also bringing him closer in appearance to his cherished sage, Popeye the Sailor Man, who is missing that very same optical instrument.

In the interview Rushdie proves his continued dedication to Popeye’s maxim too—“I yam what I yam.” As even during his ongoing recovery—which includes as many as three visits to the doctor a day and physiotherapy for his injured hand—he has been pondering new stories and writings. There is a play about Helen of Troy which will open in London. There is an idea for a novel inspired by Franz Kafka and Thomas Mann. And there is a potential memoir dealing with the events of the attack—an idea which “irritated” Rushdie at first, but has since captured his imagination, perhaps demonstrating once again his ability to transform what is “done to him” into a response of literary and public value.

Salman Rushdie lives. And, like his protagonist in Victory City, he will continue forging new voices, whispering them into the ears of new-born characters. No one who has followed his prolific and defiant career can have any doubt that he will ever stop—no matter what the threats against him. In that way he embodies the spirit of Pampa, his heroine, who declares with her final words as the city is besieged around her: “Words are the only victors.”