The Cause of America’s Gun-Death Epidemic? It’s Guns

When comparing state to state, and nation to nation, more firearms usually means more firearms-related deaths

The prayers for Americans murdered by guns reads like a litany: Robbs Elementary, Tops Friendly Markets, Marjory Stoneman Douglas High, Orlando Nightclub, Sandy Hook Elementary, El Paso Walmart, Columbine High, and on and on. According to the nonprofit Gun Violence Archive, through June 12th, 2022, there’ve been 260 mass public shootings (four or more shot in a single incident) in the United States since January 1st—on pace for a record year. As of June 14th, a total of 19,723 Americans died by guns from all causes: homicide, suicide, and accident. That’s about 119 per day, or five per hour, shot dead by a firearm. By the time you finish reading this article, someone will likely have died by gunshot. Why? What is the cause of gun violence?

My hypothesis should be as uncontroversial as it is obvious: guns. But for the gun, none of these mass public murders would have happened, and only a handful of those who died by gun suicide would be dead.

To be sure, every act of gun violence has a unique deeper cause. The Buffalo shooter was a white supremacist. The El Paso Walmart murderer was a racist. The Sandy Hook gunman was mentally ill. The Tulsa, Oklahoma hospital slayer was a disgruntled patient seeking revenge on his surgeon. The professional gambler who massacred 60 concert goers from a Las Vegas casino resort hotel room was, according to the Las Vegas FBI office, seeking to “obtain some form of infamy.”

In the study of causation, this is known as the overdetermination problem: Just how many causes can an effect have? For gun violence, all of the above social factors (and more) have been proposed. How should we sort them out?

No human action has a single cause, yet a focus on overdetermination can obscure our focus on the most important causes, which we target through legislation, public policy, and changing norms. There is no shortage of moral outrage over guns on both sides of the political aisle, but determining the cause of gun violence must be pursued objectively. Let’s see if we can understand the phenomenon from a scientific perspective.

One theory that’s popular among politicians and the general public is that gun violence is linked to violent video games. But the vast majority of studies find no such causal connection. For example, a 2019 study of over 1,000 teens that measured youth aggressiveness against the video games they played, published in Royal Society Open Science, found no support for the hypothesis “that recent violent game play is linearly and positively related to [caregiver] assessments of aggressive behaviour.” Other researchers have pointed out that countries such as Japan have equally high rates of consumption of violent video games but almost no gun violence. And it should go without saying that, of the tens of millions of Americans who play violent video games, the vast majority never shoot anyone or commit any acts of violence.

The reason so many people are confused by the issue of causal inference in social science—including the issue of gun violence—is that we mistake proximate explanations with ultimate explanations. JFK was killed by two bullets from an Italian-made Mannlicher-Carcano bolt-action rifle fired from the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository building by Lee Harvey Oswald. That Oswald was a psychopathic hate-filled anti-Kennedy pro-Castro Communist in search of notoriety (i.e., the ultimate explanation) is secondary to what is important in determining the proximate cause of Kennedy’s death—Oswald’s gun.

Or consider another example, this one drawn from Judea Pearl’s 2020 book, The Book of Why: The New Science of Cause and Effect. When a death-row prisoner is shot dead by a firing squad, what is the cause of his death? The bullet from the gun that hit him, obviously. But no one holds the members of the firing squad morally culpable, especially since there are usually multiple shooters (so no one rifleman knows who actually killed the prisoner); and in any case, they were ordered to do so. So the causal chain moves up to the officer who gave the command to shoot, and further up the chain to the prison warden who ordered the procedure that day, and further still to the court case that determined the death penalty in the case, and finally to the legal regime that legalized capital punishment in the first place.

The reason why the causal analysis is different in these two cases—Oswald’s assassination of JFK versus a state-ordered firing squad—is that the former was a crime perpetrated voluntarily by one person, while the latter is an officially state-sanctioned killing.

Most perpetrators of gun violence fall into the former category, since no one has ordered them to kill anyone (except in the case of, say, drug-cartel foot soldiers, or a Mafioso execution). Unlike with officially sanctioned killings, the proximate cause of illegal gun violence is guns, full stop. All other explanations on offer—mental illness, racism, white supremacy, a culture of violence, raging hormones, maleness, and the like—are really attempts at finding an ultimate explanation. These are important, but they don’t inform policy decisions as readily as most of us would like when we demand that the government “do something.”

One method of controlling for such confounding variables is what is called the Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT), in which individuals are randomly assigned either to the experimental treatment group that receives X, the placebo group that receives a fake X, and the control group that receives no X. The effects on some dependent variable, Y, are then compared. The problem with RCTs is that while they’re great if you’re trying to study if, say, Tylenol helps alleviate the effects of arthritis, they can’t be conducted (for ethical and/or practical reasons) in regard to a lot of problems we care about, such as the health effects of smoking among teenagers. (Imagine the public reaction if researchers recruited high-school students, and instructed some of them to smoke cigarettes for a year, while handing out fake cigarettes to others, and paying a third group not to smoke anything.)

In those cases, what we do instead is study so-called natural experiments—in which (to take the smoking example) we compare the health outcomes of people who smoke with the health outcomes of those who don’t, while doing our best to control for other factors (such as diet and exercise).

When it comes to natural experiments involving guns, the most cited study in support of gun control came out of Australia following the 1996 Port Arthur firearm massacre, in which a 28-year-old man killed 35 people and wounded another 23 with an AR-15 assault rifle—the civilian variant of a weapon designed by the US military to rapidly kill as many people as possible. Following this crime, Australian state governments agreed to ban semi-automatic and pump-action shotguns and rifles through a set of gun-law reforms.

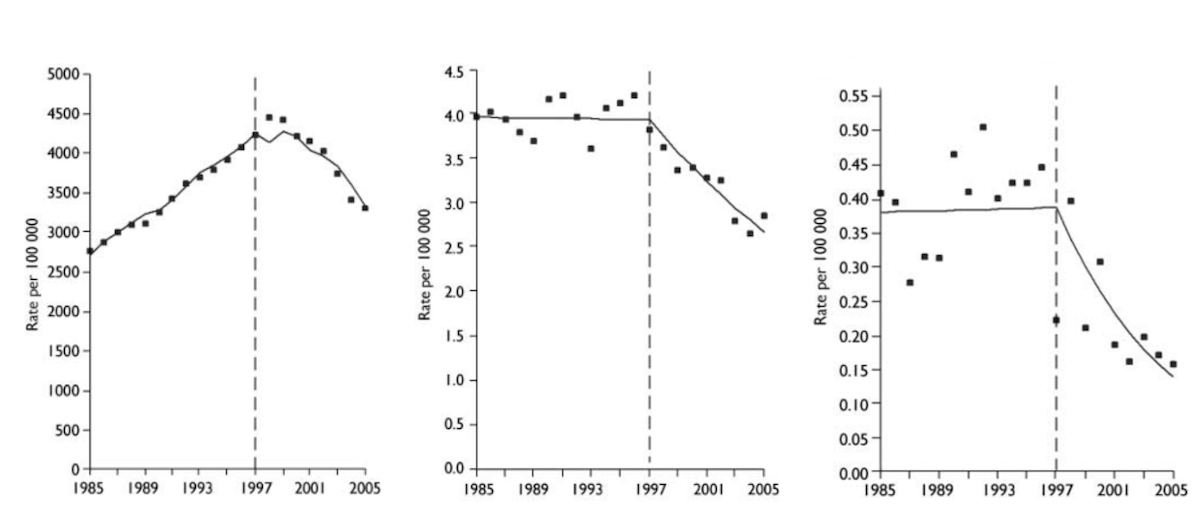

A 2006 follow-up study measured “changes in trends of total firearm death rates, mass fatal shooting incidents, rates of firearm homicide, suicide and unintentional firearm deaths, and of total homicides and suicides per 100,000 population.” It showed that in the 18 years before the gun-law reforms were implemented, there were 13 mass shootings in Australia; while in the decade following those reforms, there were none. The authors concluded:

Australia’s 1996 gun-law reforms were followed by more than a decade free of fatal mass shootings, and accelerated declines in firearm deaths, particularly suicides. Total homicide rates followed the same pattern. Removing large numbers of rapid-firing firearms from civilians may be an effective way of reducing mass shootings, firearm homicides, and firearm suicides.

The researchers also found “no evidence of substitution effect for suicides or homicides,” and “the rates per 100,000 of total firearm deaths, firearm homicides, and firearm suicides all at least doubled their existing rates of decline after the revised gun laws.”

Another case study is Austria, which in 1997 passed gun-control legislation in line with a European Council directive on controlling the acquisition and possession of weapons. That country restricted firearm purchases, upped the minimum age to purchase a firearm to 21, included an extensive background check and three-day cooling-off period, required buyers to indicate a reason for the gun purchase, added psychological testing for obtaining semi-automatic firearms and repeating guns, and required that buyers have safe firearm storage. A decade later, the British Journal of Psychiatry published an article entitled “Firearm Legislation Reform in the European Union: Impact on Firearm Availability,” in which University of Vienna Professor Nestor D. Kapusta and fellow researchers concluded that—as the figures reproduced below indicate—“the introduction of restrictive firearm legislation effectively reduced the rates of firearm suicide and homicide.”

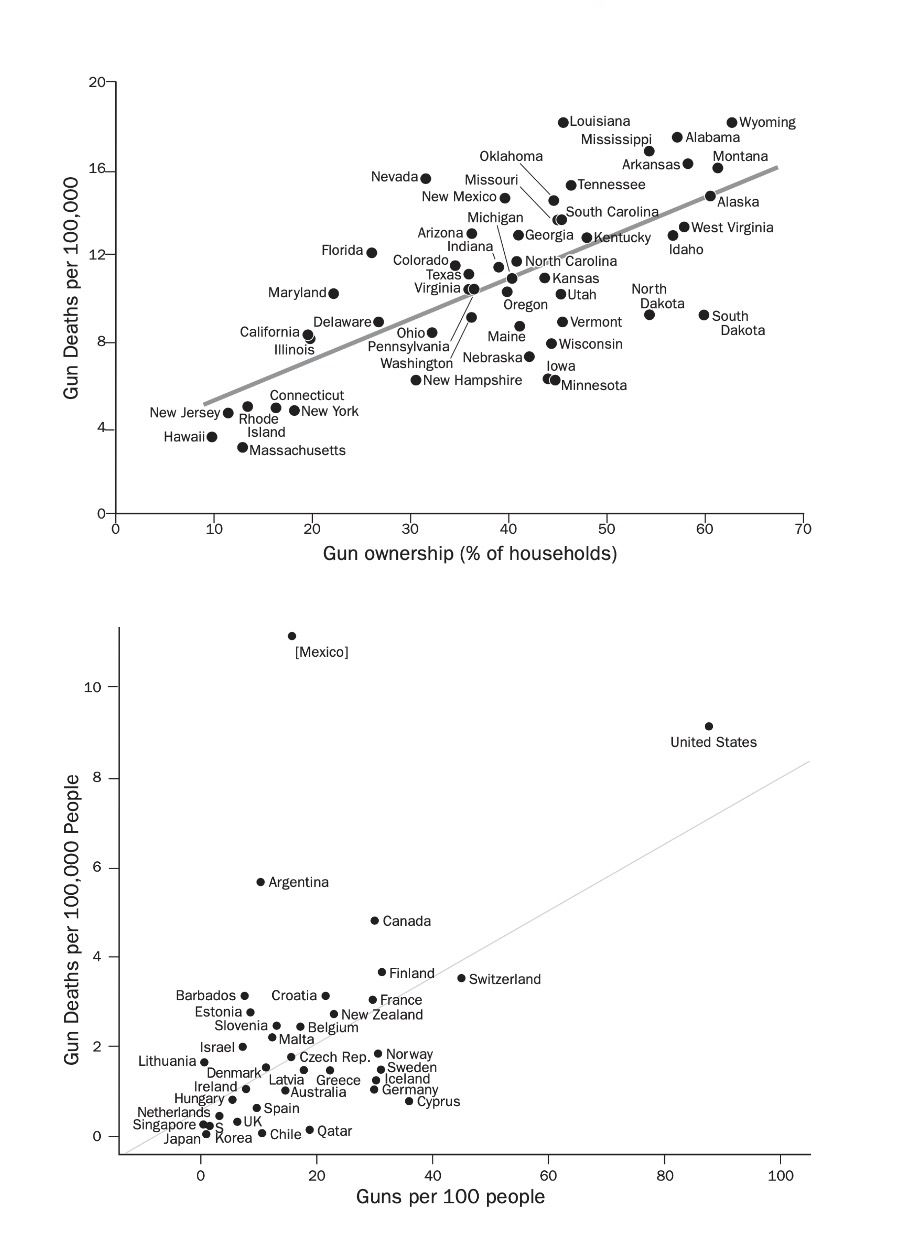

Let’s look at some additional examples of natural experiments. The figures below show (a) the relationship between gun ownership in different US states and gun deaths per capita, with a best-fit regression line showing that more guns are associated with more deaths; and (b) a cross-nation comparison showing the relationship between per capita guns and per capita gun deaths, with a best-fit regression line revealing, once again, that more guns correlates with more deaths (with the United States being an extreme outlier in regard to both variables).

In a comprehensive 2011 study reported in the Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, researchers compared the United States to 25 other high-income countries in regard to homicide, suicide, and unintentional gun deaths among five- to 14-year-old children. The results were reported as a series of ratios, expressing the US rate as a multiple of the average for 25 other high-income countries.

For non-gun-related homicides, the ratio was 1.7 to one, indicating that per-capita homicide deaths among US five- to 14-year-old children were found to run about 70 percent higher than the average for other wealthy nations. But for gun-related homicides, the ratio was an astonishing 13.2 to one.

The pattern was similar for suicide. In the case of non-gun-related suicides, the ratio was found to be 1.3 to one, indicating that per-capita suicide deaths among US five- to 14-year-old children were found to run about 30 percent higher than the average for other comparable nations. Where the suicides are gun-related, on the other hand, the ratio is 7.8 to one. And in the category of unintentional gun deaths, the ratio was found to be 10.3 to one.

In other words, for rates of non-gun-related homicides and suicides, there’s a significant but not startling difference between the United States and other Western nations. But the ratio shifts dramatically, almost by a full order of magnitude, once someone picks up a gun. And the reason isn’t complicated: Guns are far less forgiving than other methods of attempted homicide and suicide. When a couple of drunken guys get into fisticuffs at a bar, it mostly results in bruised bodies and egos, but add a gun into the mix and someone is likely going to the morgue while the other is headed to prison.

When people attempt suicide, they don’t always want to kill themselves. According to my friend and colleague Dr. Ralph Lewis, a psychiatrist who treats people in crisis, many say, “I don’t know what came over me. I don’t know what I was thinking.” An overdose of medications or a botched attempt at slit wrists may grant someone a second chance at life. With guns, that is much less likely.

As well, consider the fact that, homicide excepted, crime rates in the United States are comparable to those in other Western countries that have few guns‚ including rates for car theft, burglary, robbery, sexual assault, aggravated assault, and adolescent fighting. It’s US homicide rates that are a category of their own—because of guns.

If it isn’t clear by now that the primary cause of gun violence is guns, and that curbing their availability and capacity can attenuate the resulting carnage (though such measures cannot eliminate it entirely), let me offer a few additional observations, starting with the popular meme among gun-rights activists that if guns are outlawed, only outlaws will have guns.

This slogan simply isn’t true. Gun-control legislation does not mean outlawing guns any more than the licensing and regulation of automobiles means that only outlaws will have cars. The 1934 National Firearms Act, regulating the manufacture and sale of machine guns (and backed by the National Rifle Association at time), did not result in only outlaws having machine guns. Where is today’s George “Machine Gun” Kelly? He’s not around, because machine guns are regulated and restricted. This is the kind of rational gun control that even today’s more militant NRA can (or at least should) get behind.

Then there’s NRA Executive Vice President Wayne LaPierre’s oft-quoted proclamation, “The only thing that stops a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun.” The May 24th Uvalde, Texas massacre of 19 children and two adults put the lie to this trope, as well-armed good guys spent over an hour restraining parents desperate to rescue their children while the mass murderer continued his slaughter inside the elementary school. More generally, the NRA’s solution to crime and violence—of arming everyone and hoping the good guys out-gun the bad guys—contravenes our understanding that, except in rare and exceptional circumstances, designated law-enforcement officials have a monopoly on the use of force. In essence, the NRA is presuming America to be an effectively lawless society in which might makes right, so let’s all arm ourselves to the teeth.

If the “good guy with a gun” is an appropriately armed and professionally trained member of the police or military who routinely practices his craft at shooting ranges and in simulation drills, then yes, the deployment of such officers is one among many factors that has contributed to the decline of peacetime violence over the centuries. But if “good guys” is taken to mean armed private citizens with little to no gun training, this could not be more mistaken. A brief scan of YouTube videos under the search string “gun mishaps and negligent discharges” (or any similar search) will provide hours of darkly entertaining—and sometimes unspeakably tragic—gun accidents due almost entirely to human error.

This week, there is cautious optimism in Washington as 10 Republican senators broke ranks with their party by working with Democrats toward modest legislative steps to prevent school shootings—including mandating additional scrutiny of young gun buyers. Even if the legislation passes, no one is pretending that it comes close to comprising the sort of comprehensive gun-control reform that America requires. But at the very least, it shows that even some conservative politicians are beginning to wake up to the fact that America’s status-quo policy is tragically misguided.