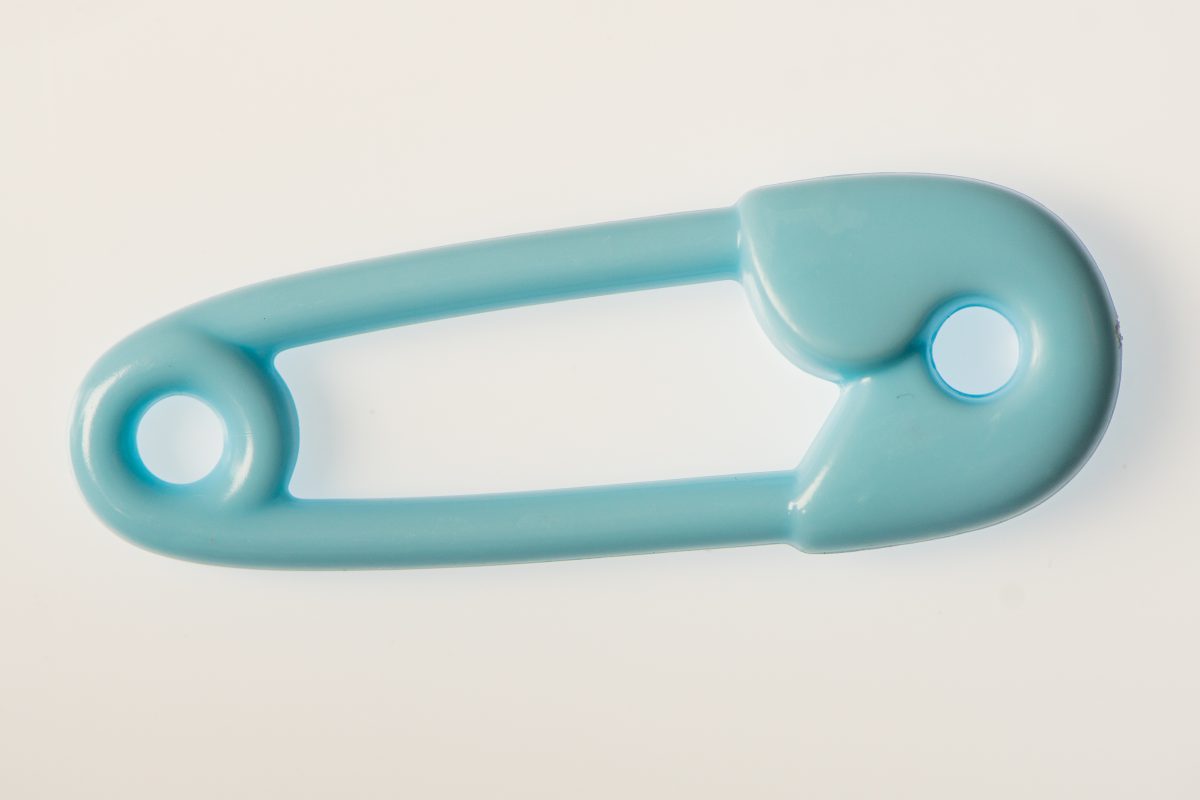

Is Safetyism Destroying a Generation?

Students now work in tandem with administrators to make their campus ‘safe’ from threatening ideas.

A review of The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure by Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt, Penguin Press (September 4, 2018) 352 pages.

In recent years behaviours on university campuses have created widespread unease. Safe spaces, trigger warnings, and speech codes. Demands for speakers to be disinvited. Words construed as violence and liberalism described as ‘white supremacy’. Students walking on eggshells, too scared to speak their minds. Controversial speakers violently rebuked – from conservative provocateurs such as Milo Yiannopoulos to serious sociologists such as Charles Murray, to left-leaning academics such as Bret Weinstein.

Historically, campus censorship was enacted by zealous university administrators. Students were radicals who pushed the boundaries of acceptability, like during the Free Speech Movement at UC Berkeley in the 1960s. Today, however, students work in tandem with administrators to make their campus ‘safe’ from threatening ideas.

Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff’s new book, The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure, persuasively unpacks the causes of the current predicament on campus – which they link to wider parenting, cultural and political trends. Haidt is a social psychology professor at New York Universityand founder of Heterodox Academy. Lukianoff is a constitutional lawyer and president of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education. In 2015, they wrote The Atlantic cover story of the same name.

Haidt and Lukianoff’s explanation for our era of campus craziness is primarily psychological. In sum, a well-intentioned safety culture which has led to ‘paranoid parenting,’ and screen time replacing unstructured and unsupervised play time, has created a fragile generation. Haidt and Lukianoff focus on people born after 1995, iGen or Generation Z, who began attending college in the last five years – just when things started to escalate.

This cohort is experiencing a dramatic rise in anxiety, depression and suicide. When they arrived on campus, in an increasingly polarised political climate, they were unprepared to be intellectually challenged. They – or at least the ‘social justice’ activists of this generation – responded by creating a culture of censorship, intimidation and violence, and witch hunts against non-believers. Universities, led by risk adverse bureaucracies, are treating students like customers and allowing an aggressive, censorious minority set the agenda.

The dangers of safety culture

Haidt and Lukianoff focus on the unintended consequences of safetyism – the idea that people are weak and should be protected, rather than exposed, to challenges. Safety culture has the best of intentions: protect kids from danger. It began with a focus on physical safety – removing sharp objects and choke hazards, requiring child seats, and not letting children walk home alone. Safety, however, has experienced substantial concept creep. It now includes emotional safety, that is, not being exposed ideas that could cause psychological distress. Taken together, the focus on physical and mental safety makes young people weaker.

Humans are what author and statistician Nassim Nicholas Taleb calls ‘antifragile’. We ‘benefit from shocks; [humans] thrive and grow when exposed to volatility, randomness, disorder, and stressors and love adventure, risk, and uncertainty’. Peanuts are a case in point of needing to be exposed to danger to build resilience. From the 1990s, parents were encouraged to not feed children peanuts, and childcare centres, kindergartens and schools banned peanuts. This moratorium has backfired. The LEAP study (Learning Early About Peanut Allergy) found that not eating peanut-containing products during infancy increases allergies. The researchers recruited 640 infants with a high risk of developing peanut allergy. Half were given a peanut-containing product. The other half avoided peanuts. The study found that 17 per cent of those who did not consume peanuts developed an allergy by age 5, compared to just 3 per cent of those who did consume the peanut-containing snack. Our immune system grows stronger when exposed to a range of foods, bacteria, and even parasites.

Antifragility applies to emotional health as well. When you guard children against every possible risk – do not let them outside to play or walk home alone – they exaggerate the fear of such situations and fail to develop resilience and coping skills. Stresses are necessary to learn, adapt and grow. Without movement, our muscles and joints grow weak. Without varied life experiences, our minds do not know how to cope with day-to-day stressors. Measures designed to protect children and students are backfiring. Fragility is a self-fulfilling prophecy. If you think certain ideas are dangerous, or are encouraged to do so by trigger warnings and safe spaces, you will be more anxious in the long run. Intellectual safety not only makes free and open debate impossible, it setting up a generation for more anxiety and depression.

Haidt and Lukianoff use an array of data that shows a shocking increase in American youth anxiety, depression, and suicide in the last five years, but particularly for young women. By 2016, one out of every five American girls met the criteria for having experienced a major depressive episode in the previous year – an increase of almost two-thirds over five years. There has also been an increase in male suicide by one-third, and female suicide has doubled since the early 2000s, reaching the highest recorded since 1981.

Notably, it is not just the American mind that has been coddled. Consistent with Haidt and Lukianoff’s findings in the United States, there has been a substantial increase in youth mental health issues in other Anglosphere countries such as Britain and Australia.

In July, Britain’s National Health Service reported a record 389,727 ‘active deferrals’ for mental health among people aged 18 or younger. The crisis is more pronounced among women, who have experienced a 68 per cent risein hospital admissions for self-harm over the past decade and a 10 per cent growth in anxiety. Another survey found a doubling in self-reported mental health problems among university students between 2009 and 2014.

Mission Australia’s Youth Mental Health report has found that a 23 per cent of young Australians have a probable serious mental health, an increase from 19 per cent just five years ago. A separate Mission Australia survey in 2017 found that for the first time mental health is the number one issue of national concern for young people in Australia. Meanwhile, the suicide rate among young Australians grew by 20 per cent over the last decade.

Feelings over debate

There is a link between rising mental health issues, safety culture and campus trends. It is notable how often students put censorious demands in the language of feeling safe. Students demand trigger warnings because ideas are emotionally challenging, safe spaces to hide away from scary situations, and the disinvitation of controversial speakers to feel safe on campus. While it is important to show courtesy in public debate, it is patently absurd to suggest that simply hearing an idea you dislike makes you unsafe in any meaningful way. As the old saying goes, ‘sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me’. In fact, the opposite is true, post-traumatic growth is a real phenomenon: difficult situations do make us stronger.

While America has experienced the worst of campus craziness, over-parenting and rising mental health issues correlate with similar university trends across the Anglosphere. In Britain, speakers are ‘no platformed’, and songs and newspapers are banned. In Canada, teaching assistant Lindsey Shepherd was reprimanded for showing a debate in class. In Australia, universities are adopting trigger warnings, succumbing to demands for censorship to protect ‘feelings’, and on some occasions protests have turned violent. In New Zealand last month a free speech debate was interrupted by protesters.

In recent weeks La Trobe University in Melbourne, Australia almost banned sex researcher Bettina Arndt from speaking about sexual assault issues on campus. While the university reversed their earlier decision, it nevertheless informed students that counselling would be available – solidifying the idea that the mere existence of a contrarian voice necessitates therapy. Students have continued to demand censorship of Arndt on the basis that her ideas make them feel ‘unsafe’.

In recent days the La Trobe Student Union’s student representatives released a statement calling for Arndt to be prevented from speaking. The statement mentions the word ‘safe’ a total of nine times. One of the student representatives explicitly declared that ‘What Arndt chooses to speak on makes me feel incredibly unsafe… The university is currently allowing this event to go ahead under the pretence of free speech, however I do not think free speech should come at the expense of student safety.’ This is not the language of radicals – this is young people appealing to authority figures for protection.

Safety culture undermines the entire purpose of a higher education. Universities exist to challenge students, to expand their worldview and develop their critical thinking. This is done by hearing and responding to ideas that make us feel uncomfortable. Efforts to censor speakers because they make some people feel ‘unsafe’ prevents the necessary process of argument and counter-argument in the pursuit of finding the truth.

Debate on campus is already undermined by the lack of viewpoint diversity– most academics come from a similar political pedigree, meaning students have fewer opportunities to be challenged in the first place. A lack of exposure to different ideas means a much more limited and weaker education. As British philosopher John Stuart Mill wrote, ‘He who knows only his own side of the case knows little of that.’ In other words, to make an argument thoughtfully, it is necessary to understand the counterfactual of one’s own argument.

Emotional reasoning and good versus evil

Haidt and Lukianoff argue that the focus on feelings is a symptom of a culture that encourages emotional reasoning: letting feelings guide our interpretation of reality. Students are being taught to engage in thought patterns that make the world appear more threatening – such as focusing on a worst possible outcome, overgeneralising, assuming that one knows what other people are thinking, and only seeing the negative in situations. These are the precisely the same cognitive distortions that lead to anxiety and depression (e.g. the world is a dangerous place for a person like me, everyone I know hates me, etc).

The encouragement of cognitive distortions also undermines academic pursuits. For example, the claim often made in academic fields such as critical race theory that ‘all white people are racist’ is an overgeneralisation that can lead to both anger and aggression in students who believe it.

Another untruth that has become prominent within academic and wider public discourse is the notion that life consists of many small battles between good and evil. In this framing, it is presumed that one’s opponent has the worst possible intentions, creating feelings of victimisation, anger, hopelessness in students who believe it. The notion of ‘microaggressions’ presumes many innocent comments – such as ‘I believe the most qualified person should get the job’ – are hiding underlying racist sentiments. Encouraging students to be concerned about unintended sentiments ensures that they are always suffering. And in practice, it means students do not speak their minds for fear of being misinterpreted as sexist, racist or homophobic. This is not an environment conducive to freely exploring ideas.

Haidt and Lukianoff recommend confronting this challenge by following the proven method of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). Considered the gold standard of psychological therapy, CBT focuses on not letting your feelings and cognitive distortions consume you. Exercises that are used in CBT help people to understand that situations are not black and white. Not every ambiguous interaction is designed to hurt you. Catastrophic thinking in response to negative events is largely within our control.

Hope for the future

The Coddling of the American Mind is both an enlightening but disquieting read. We have a lot of challenges in front of us. Safety culture is embedded into parenting styles. Mental health issues among young people are rapidly increasing. A censorious culture is the norm on campus. Universities are facilitating a self-destructive culture not only through speech codes, but in teaching simplistic theories about human society. Academics far too often pursue social justice causes over empirical inquiry. New ideas – like speech is violence, and therefore it is justifiable to use violence against speech – are downright frightening.

Haidt and Lukianoff conclude by offering a wide array of useful suggestions for students, parents, teachers, schools, and colleges – from choosing a college that clearly prioritises intellectual freedom, to increasing unstructured and unsupervised play time for children, and reducing screen time. They effectively mix together diagnoses of the problem, and some ideas for how to fix it.

But more fundamentally, we should not discount an entire generation. Every action has an equal and opposite reaction. Safety culture and censorship is engendering its own backlash. Arguably, more than any time in recent history, we are seeing an intellectual renaissance outside of traditional institutions such as the university. The more that some students – and administrators – seek to censor contrarian views, the more the mischievous instinct will play out, online and elsewhere.

At least from my experience on campuses across Australia, young people are thirsty to partake in the battle of ideas, challenge orthodoxies, and investigate dangerous ideas. While there are some who violently shut down opposition, there are many others who reject the imposition of safety culture. The challenges are not insurmountable.