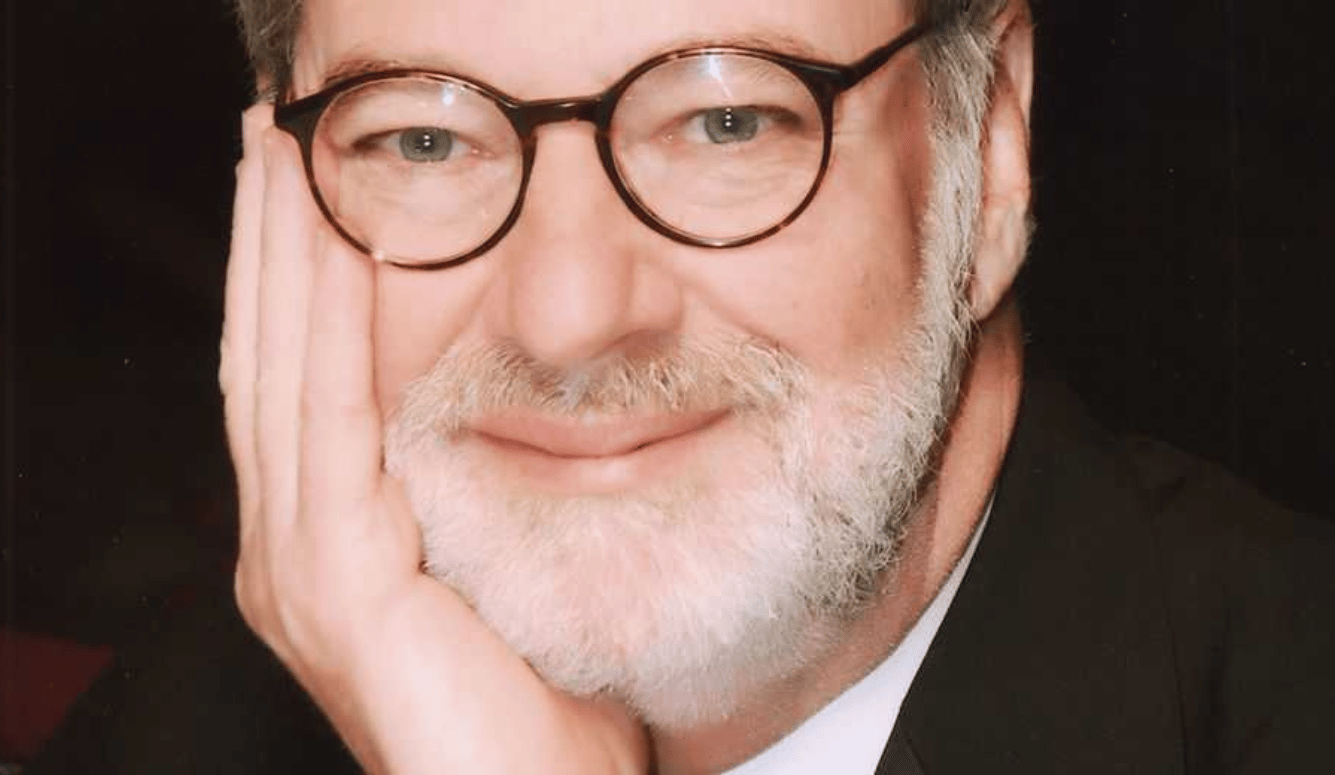

The Skeptical Optimist: Interview with Michael Shermer

An interview with the founder of The Skeptics Society.

Michael Shermer is the founder of The Skeptics Society, and its associated magazine Skeptic. He is a science writer with a monthly column in Scientific American and the author of many books including The Moral Arc: How Science and Reason Lead Humanity toward Truth, Justice, and Freedom, and, most recently, Heavens on Earth: The Scientific Search for the Afterlife, Immortality, and Utopia. I contacted Dr Shermer for an interview with Quillette: what follows is a transcript of our conversation, conducted via email.

* * *

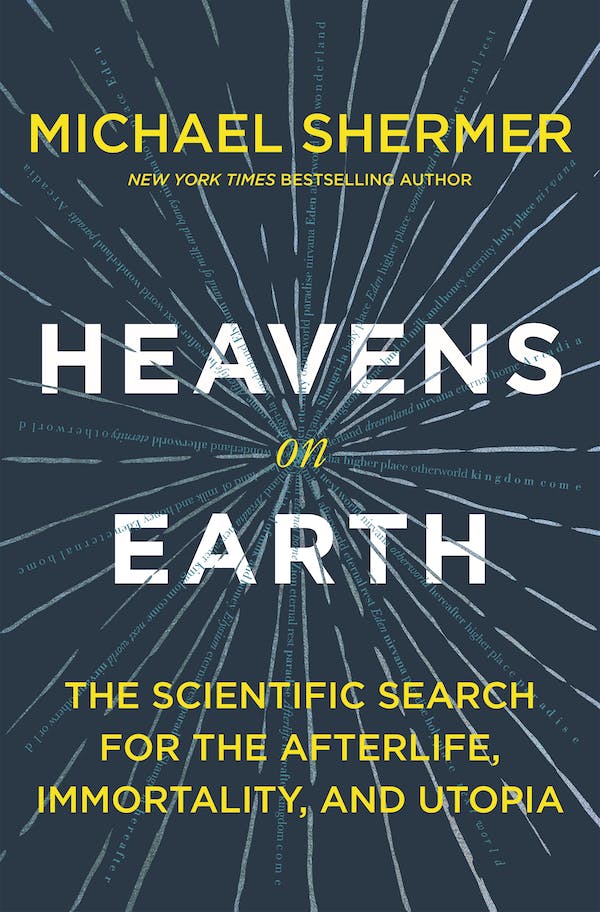

Q: Thank you for taking the time to talk to Quillette. You recently published Heavens on Earth: The Scientific Search for the Afterlife, can you briefly describe what your new book is about, and the research you did for it?

Michael Shermer: Since I just finished my book tour I can now do this while standing on one foot! Here are some take-home points:

It’s a myth that people live twice as long today as in centuries past. People lived into their 80s and 90s historically, just not very many of them. What modern science, technology, medicine, and public health have done is enable more of us to reach the upper ceiling of our maximum lifespan, but no one will live beyond ~120 years unless there are major breakthroughs.

We are nowhere near the genetic and cellular breakthroughs needed to break through the upper ceiling, although it is noteworthy that companies like Google’s Calico and individuals like Abrey deGrey are working on the problem of ageing, which they treat as an engineering problem. Good. But instead of aiming for 200, 500, or 1000 years, try to solve very specific problems like cancer, Alzheimer’s and other debilitating diseases.

Transhumanists, Cryonicists, Extropianists, and Singularity proponents are pro-science and technology and I support their efforts but extending life through technologies like mind-uploading not only cannot be accomplished anytime soon (centuries at the earliest), it can’t even do what it’s proponents claim: a copy of your connectome (the analogue to your genome that represents all of your memories) is just that—a copy. It is not you. This leads me to a discussion of…

The nature of the self or soul. The connectome (the scientific version of the soul) consists of all of your statically-stored memories. First, there is no fixed set of memories that represents “me” or the self, as those memories are always changing. If I were copied today, at age 63, my memories of when I was, say, 30, are not the same as they were when I was 50 or 40 or even 30 as those memories were fresh in my mind. And, you are not just your memories (your MEMself). You are also your point-of-view self (POVself), the you looking out through your eyes at the world. There is a continuity from one day to the next despite consciousness being interrupted by sleep (or general anaesthesia), but if we were to copy your connectome now through a sophisticated fMRI machine and upload it into a computer and turn it on, your POVself would not suddenly jump from your brain into the computer. It would just be a copy of you. Religions have the same problem. Your MEMself and POVself would still be dead and so a “soul” in heaven would only be a copy, not you.

Whether or not there is an afterlife, we live in this life. Therefore what we do here and now matters whether or not there is a hereafter. How can we live a meaningful and purposeful life? That’s my final chapter, ending with a perspective that our influence continues on indefinitely into the future no matter how long we live, and our species is immortal in the sense that our genes continue indefinitely into the future, making it all the more likely our species will not go extinct once we colonize the moon and Mars so that we become a multi-planetary species.

So what is the purpose of life? The Second Law of Thermodynamics is the First Law of Life: to push back against entropy. Everything we do comes back to this fundamental law of nature. But natural selection added something more. We do not just strive to survive, we also want to flourish, which includes much more than reproduction. Here is how I end the book (although to get the full impact reading the entire book is essential):

Facing death—and life—with courage, awareness, and honesty can bring out the best in us and focus our minds on what matters most: gratitude and love. Gratitude for a chance at life, given the biological reality that those hundred billion people who lived before us were, in fact, only a tiny fraction of the many trillions of people who could have been born but were not. The chance encounter of sperm and egg that led to each of us could just as well have produced someone else, and you would never know it because there would be no you to know. Once born, we are each unique, a concatenation of genes and brains with thoughts, feelings, memories, histories, and points of view that can never be duplicated, here or in the hereafter. Our sentience—yours, mine, everyone’s—is ours alone and like no other anywhere in the cosmos. We are given this one chance to live, some four score trips around the sun, a brief but glorious moment in the cosmic drama unfolding on this provisional proscenium. Given all we know about the universe and the laws of nature, that is the most any of us can reasonably hope for. Fortunately, it is enough. It is the soul of life. It is heaven on earth.

Q: In your career, you’ve looked closely at conspiracy theories such as belief in UFOs, BigFoot, and even Holocaust Denial and 9/11 Trutherism. Can you explain some of the common types of mistakes people make in their thinking that leads to gullibility and belief in conspiracy theories?

MS: There are several cognitive processes going on here:

Anecdotal thinking vs. statistical thinking. We evolved to do the former so it is natural; science teaches us to do the latter, and it is unnatural. What is natural is to connect two temporally-close events as causally connected. A happens and then B happens. So they must be causally connected, right? I vaccinated my child and shortly after he was diagnosed with autism. They must be connected, right? Not necessarily (and in this case definitely not).

Patternicity: the tendency to find meaningful patterns in both meaningful and meaningless noise. If you already believe in UFOs or Bigfoot, strange lights in the sky or shadowy figures in the trees are interpreted as a meaningful pattern that supports the belief. Often such patterns carry an additional component that I call…

Agenticity: the tendency to infuse those patterns with intentional agents who act in the world. From conspiracies to ghosts, angels, demons, and gods, we tend to impute agency to the goings on around us, as if there’s someone/something out there pulling the strings.

Confirmation Bias: we look for and find confirming evidence for what we already believe and ignore or rationalize away disconfirming evidence. Once you believe that, say, “the Jews” are running the world, or that the U.S. government (or the Bush administration in the case of the 9/11 truthers) is involved in vast global cabals to control oil, it is easy to interpret daily news stories about the goings on of governments in the light of the conspiracy theory in question. Every bit of minutia becomes pregnant with meaning. It’s not chance or contingency, it’s a Vast Right Wing (or Left Wing) Conspiracy!

Q: Do people believe in conspiracy theories because statistical thinking is unnatural? If more people were taught about hypothesis testing or the difficulty in proving causality would conspiracy thinking be less common?

MS: Education helps but it’s not enough. I wrote about this problem in one of my Scientific American monthly columns recently, noting that both the Right and the Left distort science in the service of their ideology. On the Right we see the denial of evolution, vaccinations, stem cell research, and global warming. On the Left we see the distortion or denial of GMOs, nuclear power, genetic engineering, and evolutionary psychology, the latter of which I have called “cognitive creationism” for its endorsement of a blank slate model of the mind in which natural selection only operated on humans from the neck down.

What can we do about this problem? First, we must acknowledge that for most issues most conservatives and liberals are pro-science. Recent surveys show that over 90 percent of both Republicans and Democrats in the U.S., for example, agreed that “science and technology give more opportunities” and that “science makes our lives better.” In other words, anti-science attitudes are formed in very narrow cognitive windows—those in which science appears to oppose certain political or religious views. Knowledge of a subject helps a little. For example, those who know more about climate science are slightly more likely to accept that global warming is real and human-caused than those who know less on the subject. But that modest effect is not only erased when political ideology is factored in, it has an opposite effect on one end of the political spectrum. For Republicans, the more knowledge they have about climate science the less likely they are to accept the theory of anthropogenic global warming (while Democrats’ confidence goes up).

In another Scientific American column I wrote about this “backfire” effect, in which the more information you give someone that contradicts a cherished belief, the less likely they are to change their mind; in fact, they double-down on the belief. But this only applies to important political, religious, or ideological beliefs.

If you don’t have a dog in the fight then the facts can change your mind. But the cognitive dissonance created by facts counter to beliefs by which you define yourself will almost always be resolved by spin-doctoring the facts, not by changing your mind. Thus, when I engage in debate or conversation with creationists, for example, I don’t give them the choice between Darwin and Jesus, because I know who’s going to lose that one. Instead, I try to convince them that evolution was God’s way of creation, just like people in Newton’s time and after came to believe that gravity was God’s way of creating solar systems. I don’t believe that myself, of course, but the point is to get people to embrace science, not to win an argument. With climate deniers, I know from research and personal experience that when they hear “global warming” they think “anti-capitalism,” “anti-freedom,” “anti-American way of life.” So I take that off the table by showing them how investing in green technology is going to be one of the most lucrative enterprises in the history of capitalism. I call this the Elon Musk Model.

Q: This is really interesting, and has implications for the way we think about sex differences research. Do you think that, when it comes to science denial (whether it is influenced by Left- or Right-leaning ideology), reframing the moral dimensions of hot-button issues will help scientific consensus to be more freely accepted?

MS: Yes, absolutely. We must separate the moral dimensions of a subject from the empirical questions surrounding it. For example, on the radioactive issue of sex (or gender) differences in cognitive abilities, there is the empirical question of whether or how men and women diverge in certain tasks, and then there is the moral question of how men and women should be treated. Empirically, there is much evidence that in some tasks women excel over men, and in other tasks, men excel over women. For example, women are more dexterous while men are better at throwing; women are superior in visual memory whereas men are better at mentally rotating shapes; women are better at mathematical calculation while men are better at mathematical problem-solving; in terms of overall general intelligence (g), however, there is no gender difference. Morally, however, none of this matters. We should support women’s rights regardless of any physical or cognitive differences between the sexes. To yoke one’s moral evaluation to empirical questions like this is a big mistake; worse is to assume that this is what people always do and therefore we must suppress any empirical evidence that there are differences, as this will only tilt people’s moral judgments toward empirical outcomes.

This reminds me of the debate in the late 1980s through mid-1990s about whether homosexuality was nature or nurture, something you were born to be or a lifestyle choice. Conservatives and Christians argued for the “choice” position and this led to efforts to “convert” gays to straight (or “pray the gay away”) because something that is learned can be unlearned. This led the gay community and supporters thereof to argue for the “born this way” position. The cumulative evidence from multiple lines of inquiry led to the nature position more than that of nurture, but this was another example of confusing the empirical question of the origin of homosexuality with the moral question of the rights of gays and lesbians (today the LGBTQ community). It should go without saying—but unfortunately in these times it must be said again and again—it doesn’t matter what the origins of homosexuality turn out to be, gays and lesbians and everyone else in the LGBTQ community are entitled to the same rights and privileges as everyone else protected by the constitution of their nation (and those nations that have yet to extend legal rights to gays and lesbians need to change their constitutions).

Q: On another subject, Christina Hoff Sommers has called Intersectionality Theory a type of conspiracy theory. Given your expertise on the psychological mechanisms of conspiracy theories, would you agree with her assessment? From your perspective do you view such theories as dangerous and in need of challenge?

MS: I don’t think that Intersectionality Theory is a type of conspiracy theory for one obvious reason: conspiracy theories always involve some element of secrecy and there is nothing secret about it! The people who practice this fatuous and polarizing set of ideas are only too happy to tell the world about their plans for taking over the academy and eventually the world with their ideology. They publish it in journals and books, pronounce it from podiums and lecterns, and scream it at protests.

More importantly, however, I do agree with Christina Hoff Sommers that Intersectionality Theory is dangerous for humanity, dissolving the complexity of human nature and culture down to an overly simple Manichean model of Oppressor and Oppressed, Them and Us, Good and Evil, and Black and White (literally and figuratively). It’s is another instantiation of Identity Politics and it is dangerous because it threatens to reverse everything that the Civil Rights movement fought to obtain, and it is the very opposite of what Dr Martin Luther King Jr. dreamed about in his most famous speech:

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

Dr. King was the inspiration for my book The Moral Arc, in which I document how we have bent the moral arc to include more people in our moral sphere. But now those who practice Identity Politics—particularly in the academy where Intersectionality Theory thrives—want to reverse Dr. King’s dream. They want everyone to be judged by the color of their skin and not the content of their character. What could be worse? Well, this: equality of outcome. This is the opposite of what Dr. King also proclaimed:

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.”

What the Founders of the United States meant (and what Dr King was emphasizing) was equal treatment under the law (which was revolutionary at that time), not equal outcomes. In this perverse reversal of reality the Hard Left, Far Left, Alt-Left, Authoritarian Left (or whatever the preferred label for the analogue to the Hard Right, Far Right, Alt-Right, and Authoritarian Right is these days) insist that any deviation from perfect representation of a cohort in a profession—say, 50/50 gender—automatically means there is discrimination and therefore inequality. This is not to argue that there is no longer any discrimination in society—of course there still is—but as I document in The Moral Arc, it is far less than it used to be and we should be celebrating this progress and figuring out what we’ve been doing right so we can do more of it. These people want to march us back to the pre-Civil Rights era and judge everyone by whatever fashionable prejudicial characteristic comes to mind: gender, skin color, etc. It’s infuriating to witness and I will stand against it at every opportunity.

Michael Shermer

Q: I know that you consider yourself to be an optimist; do you find yourself being optimistic about trends such as increasing political polarization in the United States? Lots of people seem to be deeply worried about it at the moment, and no-one really seems to know what to do about it.

MS: This too shall pass. Follow the trend lines, not the headlines. It’s now been over a year since Trump took office and the world has not ended. The wall has not been built. ObamaCare is still in place. Millions of Mexicans have not been deported. We have not gone to war against North Korea. And so on. This is a good test of my thesis in The Moral Arc. If we glide through these four (or eight) years without ruin it will show that the checks-and-balances set up by the Founders really do work.

In this sense, I’m not an optimist so much as a realist. There’s nothing inevitable about the progress we have experienced over the centuries. It is the result of strategic efforts on the part of reformers to make change happen in the direction of moral progress. Again, Dr. King is my case study: those counter sit-ins, bus strikes, and rights marches were anything but random and spontaneous. They were calculated to optimize media attention in order to bring about changes in the laws where they were most needed.

There’s a reason King organized the 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery in Alabama, the Southern state with the most deeply entrenched racist policies whose Governor, George Wallace, was a notorious racist who opposed desegregation. That’s how real change takes place. This is the very opposite of the student protests against speakers like Milo Yiannopoulos, Ben Shapiro, Charles Murray, and Heather Mac Donald that we’ve witnessed in recent years on college campuses. Not only are these moralizing students not going to achieve the goals (such as they are) they aim for (“social justice”?), they will have the opposite effect. They need to read more about what true civil libertarians do to bring about real justice.

Q: So, in other words, should we be hopeful that movements which are the enemies of reason (i.e. white identitarianism, intersectionality and so on) will exhaust themselves, and eventually burn out?

I am hopeful that they will, yes, because such movements are not sustainable. The arc of the moral universe is bending toward treating people as individuals, not as members of groups, so identity politics is on the wrong side of history.

Q: But what do you think about the impact of social media? While crazy religious or political movements are nothing new, social media is a recent invention, on a par with something like the printing press in terms of its sociocultural impact. And the printing press ushered in the Reformation, which sparked about two centuries of religious wars, didn’t it?

MS: Indeed, the same device that printed Shakespeare also printed Mein Kampf. We can’t simply assess the value of a technology based on its products. All such game-changing technologies can and will be used for good and evil. The solution is counter-technologies, such as fact-checking sites like Snopes.com, FactCheck.org, OpenSecrets.org, and PolitiFacts.com, the latter of which fact-checks politicians’ speeches in real time and shortly thereafter rates them as True, Mostly True, Half True, Mostly False, and Pants on Fire. As PolitiFact’s editor Angie Holan explained: “Journalists regularly tell me their media organizations have started highlighting fact-checking in their reporting because so many people click on fact-checking stories after a debate or high-profile news event.”

Before we think about passing top-down laws to curb the abuses of social media, let’s work toward and support bottom-up solutions such as these. Social pressure that leads to reputational damage control, as we saw recently with the promises of Mark Zuckerberg to fix Facebook, are encouraging. This is yet another soluble problem that is being solved.

Q: As a skeptic, can you tell me some figures that you look up to in terms of their ability to think open-mindedly but also with a healthy skepticism? Who are some figures that you think young people should read if they want to develop their own critical thinking?

MS: In my undergraduate training, my philosophy professor Richard Hardison and psychology professor Ola Barnett taught me to think critically about all issues; in graduate school my thesis advisor the experimental psychologist Douglas Navarick taught me to think like a scientist, while the evolutionary biologist Bayard Brattstrom and animal behaviorist (ethologist) Meg White gave me a deeper foundation for understanding human nature. In my PhD program in the history of science, Richard Olson helped me navigate the treacherous waters of the postmodern/deconstructionist movement of the 1980s that was influencing how scholars thought about how science operates in a cultural context. More generally, and to your question, Carl Sagan and Stephen Jay Gould were my mentors for writing and thinking as a public intellectual, and today I continue to be motivated to write, speak, and think as clearly and effectively as my friends Richard Dawkins, Steven Pinker, Sam Harris, Daniel Dennett, Carol Tavris, and of course the late great Christopher Hitchens, whose rhetorical skills with both the pen and the podium were unmatched but left a mark at which we can all aim.

Q: Indeed, they are all impressive figures. (Although I know that Gould has attracted ire for politicizing sociobiology and psychometric research – perhaps a topic for another time!)

MS: The case of Gould is an unfortunate one. He was so brilliant and such a gifted writer, and he was always a friend and supporter of mine who only ever treated me with respect and friendship. So it is difficult for me to accept the stories of others who he treated very badly. But it appears that there were a number of people who had very different experiences with Steve than I did, and the stories are not at all flattering.

Q: Are there any thinkers you admire today of the younger generation? From my perspective, I am optimistic about the state of intellectual heterodoxy because I see many high quality submissions come through Quillette’s inbox. And several young people such as Lindsay Shepherd and James Damore (and several of Quillette’s writers) have been inspiring in the way that they have resisted contemporary dogmas to defend the principles of open inquiry — despite the personal costs. Do you share in this optimism?

MS: The writers that you have curated at Quillette, along with those that Pamela Weintraub has edited and published at Aeon, are two very encouraging signs of the intellectual vibrancy of the next generation. I see this daily on social media as a regular consumer of intellectual content. I can’t seem to stop reading article after article as hours fly by in the day, all high quality, well written, artfully edited, deeply researched, and delightfully entertaining on any number of subjects that interests me, that at some point I have to force myself to stop and get back to my own writing and editing or else the entire day will disappear.

I see it weekly in my students at Chapman University, and in young and upcoming scholars and scientists I meet at conferences and gatherings like TED. It’s another example of the Flynn Effect, in which I.Q. scores are going up about 3 points every decade, or one full standard deviation in half a century. That’s huge! When I growl “kids these days!”, instead of complaining about the decline of mores and customs, I mean it to indicate how much smarter younger people are today than in my generation. And I’m glad for it because I’m hoping that they solve the big problems before I hit the wall!

Q: We are at an interesting point in history, wouldn’t you agree?

MS: Every generation thinks it is special, and no doubt 500 years from now people will be as amazed at how singular and distinct their time is as we are today, but looking backwards instead of forwards, one would be hard-pressed to find a comparable period in history to ours. You mentioned the printing press, which was a game-changer, but its effects took centuries to unfold. The Internet is doing the same in timescales of years. The world has changed more in my lifetime than it has since the time of Julius Caesar to my birth in 1954. Making it all the more likely that by the end of the 21st century there will have been more change than in all previous centuries combined. Interesting indeed.

Michael Shermer is a science writer, author of several books, and the founder of The Skeptics Society and Skeptic magazine. His latest book Heavens on Earth: The Scientific Search for the Afterlife, Immortality, and Utopia is on sale now via Amazon.

Claire Lehmann is the founder and editor of Quillette.