Long Read

The One State Delusion

Instead of becoming a poster boy for globalism, Barcelona has been the setting for a powerful Catalan nationalist movement demanding outright independence.

If you are an ardent champion of globalism, imagining how the economic and cultural interaction across political borders not only makes us more prosperous but also challenges the archaic concept of the nation-state, then Barcelona, Spain, is probably your kind of town.

Barcelona, one of the world’s major global cities, is the sixth most populous urban area in the European Union (EU) and the largest metropolis on the Mediterranean Sea, has been transformed from a manufacturing centre, the so-called Manchester from Catalonia, into a knowledge-based economy, a leading tourist and commercial centre, that has been attracting international businesses and skilled professionals.

Smart, innovative, cool, hip, with world-class conferences and expositions and many international sport tournaments, and one of the fastest growing economies in Europe Barcelona, the capital of the region of Catalonia, should be a poster boy for globalism.

It’s Nationalism, Stupid!

Indeed, if you examine much of the evolving conventional wisdom on the current political backlash against international trade, immigration and globalization in general, Barcelona, not unlike New York City and London is one of those “global cities,” where multiculturalism reigns, immigrants are welcomed, and where young and highly-educated knowledge professionals should be defending globalism against the threats posed by xenophobic politicians espousing nationalism, separatism, tribalism, and nativism.

At the same time, according to numerous political scientists, nationalism rears its ugly head in those parts the country that exhibit de-industrialization and the ensuing economic decline, like the Rust Belt areas of the United States or the Midlands in England, where Trumpism and Brexit had won respectively. Identitarianism, in its many forms, has been backed by older and unemployed voters with no college degrees and few skills that could be utilized in our high-tech economy.

But this socio-economic model does not explain why Barcelona has become the heart of the current nationalist resurgence in Catalonia. In fact, the rise of nationalism in Catalonia has been taking place in the last two decades, just as the region with Barcelona at its heart, has been experiencing tremendous economic growth fuelled by globalization.

Instead of becoming a poster boy for globalism, Barcelona has been the setting for a powerful Catalan nationalist movement demanding outright independence, that declared victory in the 2015 regional election, and then held a referendum on the issue last October, when 90 percent of the 2.26 million who voted have chosen independence from Spain.

Strong opposition from the Spanish government as well as from the EU to the idea of Catalonian independence would probably put any move towards secession on the backburner for a while. But there is no reason to believe that the worldwide tide of nationalism will ebb anytime soon or to assume that the Catalonians, or the Scots in Great Britain, who are demanding the right for national self-determination, are propelled mostly by economic anxiety and driven by nativist sentiments that reflect the public backlash against the growing Muslim immigration into Europe.

Which is the way proponents of globalism are explaining the rise to power of nationalist political parties in Hungary, Poland, Austria and the Czech Republic, not to mention the electoral gains made by the Alternative for Germany and Marine Le Pen of the National Front of France.

But then, it is in two of the most economically prosperous areas in Europe, Catalonia and Scotland, as well as in northern Italy, Germany’s Bavaria and the Flemish part of Belgium that the pressure for national secession has been growing in recent years.

At the same time, nationalist leaders have come to power in Japan, China, India, and Turkey, at a time when those countries have been experiencing economic growth and have certainly not been facing any tide of illegal immigration.

Hungary, Poland, and the Czech Republic have emerged out of the communist era with strong economies and are now members of the EU. And while a small trickle of immigrants from the Middle East does not pose an existential threat to these countries, it does help accelerate the trend towards nationalism that would have occurred anyway.

Roots and Wings

To put it differently, you do not have to live in a backward rural area or to be an unemployed worker without a college degree, who is being bullied by Muslim or Hispanic immigrants, to feel the gravitating power of identity, of nationalism, ethnicity, religion or, for that matter, tribalism.

In a way, the cheerleaders for globalism, such as the New York Times columnist Tom Friedman have created a false dichotomy between the good guys (globalists) and the bad guys (nationalists). Hence the globalists have supposedly embraced the principles of free markets, free trade and free immigration and have chosen to create a more prosperous world free of conflicts between ethnic groups, religions and nations.

The nationalists, on the other hand, have been promoting the anachronistic values of identity driving a political backlash against globalization, calling for restrictions on the flow of capital, goods, and people, and celebrating various forms of tribalism.

In reality, what has happened is that “Friedmanism,” the grand theory that the economic forces of globalization would overcome nationalism and ethnic and religious conflicts proved to be an illusion, just as other notions of economic determinism—Marxism being the prime example—failed to materialize.

The Economic Man did not defeat the Political Man.

Humans desire to preserve their individual identity, to have wings to fly and to gain economic freedom. But they also want to belong to a group, to maintain a sense of collective identity, to have roots in the past. When these two colliding needs are not in balance, a political backlash to achieve new equilibrium is inevitable.

Which is exactly what is happening now in one way or another across the globe. Whether you are a Pole or a Czech, a Catalonian or a Scot, a Chinese or an Indian, you do not want to lose your wings by totally closing your country’s borders to trade, immigration or cultural exchange, but to affirm your roots and ties to your community instead of being force to give them up in the name of vague universal values.

An independent Catalonia or Scotland can still be a member of the EU, and as the Poles or Hungarians suggest, membership in the EU does not mean that your prime allegiance to your own nation-state is overridden as a result of being part of a supranational grouping. Borders and Walls do make for good neighbours.

From the Arab Spring to Tribes with Flags

Nowhere has the tide of nationalism been more powerful than in the Arab Middle East. At one point, Friedman and other globalism cheerleaders were imagining that the ousting of Saddam Hussein and the “liberation” of Iraq would lead to the “export” of democracy to Mesopotamia and to the remaking the Middle East along liberal lines.

Later on, the so-called Arab Spring was integrated into this globalism narrative and portrayed initially as a movement headed by young westernized Facebook users demonstrating in Tahrir Square promoting liberal-democratic values, including religious freedom and women rights.

But the end result was not a Middle Eastern version of the 19th Century Europe’s Spring of Nations but the collapse of the regional political status quo, and the unleashing of ethnic, sectarian and tribal conflicts that have ignited bloody civil wars, horrific violence, strengthened the hand of Sunni and Shiite fundamentalists, and that led eventually to the disintegration of existing states, including Iraq, Syria, Yemen and Libya.

In reality, those and other states that constituted what became to be known as the Arab World, were artificial political entities created by Great Britain and France, the victorious European powers who had defeated the Ottoman Empire during World War I and which failed to reflect the ethnic, sectarian and tribal makeup of the region.

To put if differently, the Iraqi, Syrian, Yemenite and Libyan “nations” were mostly a product of the creative minds of British and French officials. They were trying to maintain their respective interests of their empires and the balance of power in the region by forming states that brought together a mishmash of peoples, Arab-Sunnis and Arab-Shiites and Kurds and Armenians, numerous Christian communities, including Assyro-Chaldeans, Arameans, Maronites, and Copts, as well as tribal groups like North Africa’s Berbers and those inhabiting the Arabian Peninsula, Libya and Sudan.

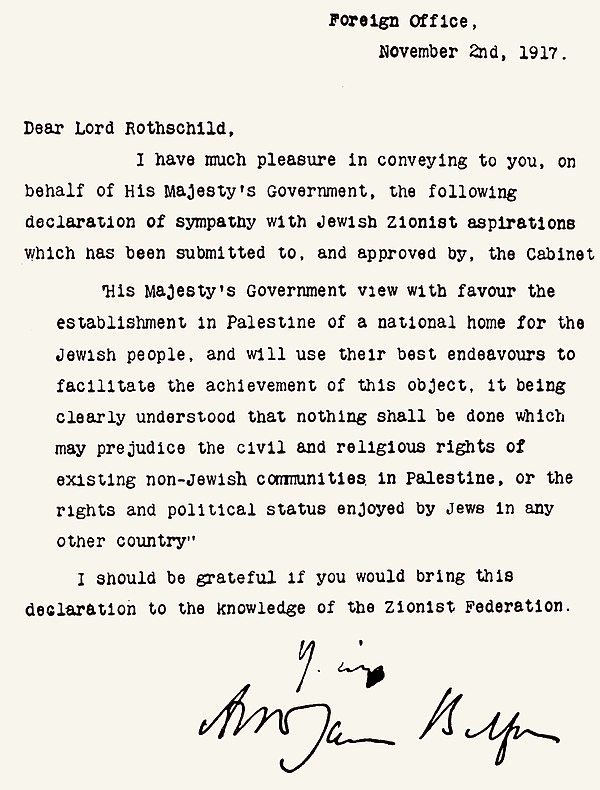

In that context, only one non-Arab national movement, Zionism, gained recognition by the western power after WWI, in the form of the Balfour Declaration issued by the British government, announcing support for the establishment of a “national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine.

The post-WWI Middle East state system was kept in place during the global competition of the Cold War which was also dominated by the Arab states and Israel, with non-Arab states of Turkey, Iran and Ethiopia exerting their influence on the periphery on the region.

The collapse of this Middle East state system in the aftermath of the Iraq War and the Arab Spring, re-energized the old ethnic, sectarian and tribal identities that had been kept dormant for close to a century. What some perceived to be a monolithic Arab World can now be seen for what it is, a mosaic or a kaleidoscope consisting of many identities, Arab and non-Arab (Berbers; Kurds), Muslim and non-Muslim (Maronites; Copts), those with ancient geographical and historical roots (Egypt; Morocco) and those that are more recent constructions (Iraq; Saudi Arabia), joined by the non-Arab states of Turkey and Iran.

While much of the current international attention has been on the evolving struggle or “cold war” between Arab Sunnis and Arab Shiites, with a powerful non-Arab regional power, Iran, mobilizing the Shiite forces, it is the re-emergence of the Kurdish national movement that could probably have a long-term and lasting effect on the evolving balance of power in the Middle East.

Indeed, at the same time that Catalonians were holding their referendum on independence last year the eight million Kurds residing in northern Iraq, where they constitute a majority, were also demanding that they be allowed to secede from Iraq and form a new Kurdish nation-state.

Iraq’s Kurds are members of a Middle Eastern ethnic group of about 30 million with a distinctive language, culture and history. They currently constitute 17 percent the country’s population have been struggling to achieve some form of independence from the Arab-controlled government in Baghdad, gaining political autonomy in the aftermath of the 1991 Gulf War and forming a Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG).

The area controlled by the KRG has expanded following the 2003 US invasion of Iraq, and the authority of the regional government was eventually recognized in the 2005 Iraqi constitution. And in a referendum held on September last year by KRG, the independence side won a 93 percent “Yes” vote.

But like in the case of the Catalonians, no one expects that an independent Kurdistan would emerge anytime soon, and for the same reason: Regional powers are concerned that a Kurdish state would harm their interests and challenge the existing status quo.

The eight million Kurds who live in northern Iraq are part of a larger Kurdish population that inhabits a contiguous area known as Greater Kurdistan, spanning adjacent parts of south-eastern Turkey or Northern Kurdistan, north-western Iran or Eastern Kurdistan. and northern Syria or Western Kurdistan.

Iraq, fearing the loss of a third of its country, as well as oil and natural gas reserves, and its two powerful neighbours, Turkey and Iran, worry that independence for Iraq’s Kurds would encourage separatist drives among their own large Kurdish minorities. So they are expected to use their political and military power to thwart Kurdish secession from Iraq, and are already taking steps to isolate the KRG.

But even under the least-favourable scenario from the Kurdish perspective, any agreement on the status of Iraq would have to include providing political autonomy to the Kurds in northern Iraq. This would have to be done as part of a decentralized Iraqi system under which the dominant Arab Shiite majority would also have to recognize the interests of the members of the Arab Sunni minority.

Similar arrangements would have to be part of agreements to end the civil wars in Syria, Yemen and Libya. Otherwise, the pressure for the secession of their many communities could lead eventually to the partition of these countries along ethnic, sectarian, and tribal lines, in the way the mostly Christian inhabitants of southern part of the country seceded from Sudan in 2011, to create the independent Republic of Sudan.

Two States for Two Peoples

In a way, such a model exists today in the form of the so-called two-state solution, aimed at bringing an end to the over-a-century-long conflict between Israeli Jews and Palestinian Arabs over the area between the Mediterranean and Jordan, which each community regards as its national homeland, the Land of Israel vs. Arab Palestine.

In fact, the concept of partitioning the Holy Land between the Jews and the Arabs has been recognized by the international community since the United Nations General Assembly had passed a resolution on November 1947. The resolution was to divide the former territories of the Ottoman Empire that the League of Nations had granted Britain as a mandate in 1922 into a Jewish State and an Arab State.

Part of the territory, west of the Jordan River, Transjordan, became largely autonomous under the British in 1928, and fully independent in 1946, and is known as the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. After the Palestinians had rejected the 1947 partition plan, and Israel was established as an independent state in 1948, Egypt took over the Gaza Strip while Jordan annexed the West Bank including East Jerusalem.

Since Israel occupied the West Bank and Jordan after the 1967 Middle East War, the political future of these Palestinian territories has become central to a series of negotiations held under American and international auspices to reach peace between Israel and its Arab neighbours.

Initially, negotiators considered plans to return the West Bank to the control of Jordan, as part of an Israeli-Jordanian peace agreement, under which a Jordanian-Palestinian confederation would also govern the Gaza Strip.

But the emergence of Palestinian Arab national movement led by Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), calling for the creation of a unitary Arab Palestinian State that would also include, in addition to the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, the territory that constituted the State of Israel, and launching terrorist attacks against the Jewish State and its international supporters, resulted in discarding of the idea of a Jordanian-Palestinian confederation and the focusing of diplomatic efforts on the establishment of an independent Palestinian State.

Mirror-imaging the PLO’s original vision of eliminating the Jewish State and creating a unitary Arab State or a “secular and democratic state,” a Greater Palestine, was the growing political support inside Israel for the idea of a Greater Israel, that proposed annexing the West Bank (or to use their biblical names, Judea and Samaria) and the Gaza Strip to Israel and as part of that process, encouraging Israeli Jews to settle in those territories, which Israeli governments have been doing under the pressure of the country’s nationalist and religious political parties. The bottom line was that advancing the Greater Israel and Greater Palestine meant a rejection of the two-state solution.

But secret diplomatic talks between the Israeli and Palestinian officials in Oslo, Norway, helped shift the balance of power in both camps in the other direction. Under the 1993 Oslo Accords, the PLO recognized Jewish State while the Israelis accepted the idea of establishing a Palestinian State side by side with Israel.

And while the ensuing negotiations between the Israelis and the Palestinians have failed to lead to an ultimate agreement between the two sides and to bring an end their armed conflict, both the current Israeli government and the Palestinian Authority (PA) that now governs only the West Bank have remained committed to the two-state solution.

More recently, the idea of having a Palestinian state living side by side with Israel, would become part of the so-called Clinton Parameters, the guidelines for a permanent status agreement to resolve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, that were proposed by then U.S. president Bill Clinton, following the stagnating negotiations between Israelis and Palestinians in December 2000, and were meant to be the basis for further negotiations between the two sides.

The Olive Tree vs. the Lexus

Following the collapse of the Berlin Wall and end of the apartheid regime in South Africa, and the 1993 Oslo Agreement, Friedman and other pundits were hopeful that the conflict between Jews and Arabs would also come to an end, and young Israelis and Palestinians would be forming start-ups and making money in Tel Aviv and Ramallah instead of fighting over their respective holy sites in Jerusalem.

Based on this thesis, Israelis and Palestinians were on their way to create a New Middle East that would make prophets of globalism proud. In the struggle between the Olive Tree (Friedman’s metaphor for outdated nationalism, ethnicity, and religion), and the Lexus (which stands for democracy, open markets, the free flow of information, people, and money), the Lexus was going to win.

That those were hopes were not fulfilled, and that the Olive Tree seemed to be gaining the upper hand, should not have come as a major surprise to any serious observer of the ethnic conflicts taking place in other parts of the world against the backdrop of rising nationalism.

Hence, the Turkish and Greek communities of Cyprus have been trying to reach an agreement on the political future of the island since Turkey invaded its Turkish sector in 1974, while Armenians and Azeris have been fighting since 1994 over the control of Nagorno-Karabakh, a disputed territory, internationally recognized as part of Azerbaijan.

The Yugoslav Wars of Succession, a series of ethnically based wars and insurgencies fought from 1991 to 1999/2001, in the former Yugoslavia have clearly demonstrated the enormous difficulties of reaching a solution to disputes over territories between Serbs, Croats and Albanians, who not unlike Israeli Jews and Palestinian Arabs have based their claims on historical and religious grounds.

Indeed, the issues of ethnic minorities in the new states, including in Kosovo, still remain unresolved, and reflecting the complexities of these disputes, many Greeks continue to object to the idea that one of the new republics is calling itself Macedonia, arguing that that implies a territorial claim on Greece’s northern Macedonia region.

This reality would suggest that any diplomatic effort to resolve the Palestinian-Israeli conflict would take a long time, especially when one considers some of the issues that needed to be resolved. Such issues include the sovereignty over the entirety of the West Bank and East Jerusalem, Palestinian refugees’ right of return to Israeli territory they inhabited before 1948, and the dismemberment of Israeli settlements on Palestinian West Bank territory. Not to mention the fate of the religious sites in Jerusalem.

Moreover, since President Clinton failed to broker a peace deal in 2000, political Islam has been on the rise in the Arab World, including among the Palestinians. Hamas, the radical Islamist movement that refuses to recognize Israel, scored a major victory in the 2006 election to the Palestinian Legislative Council that led eventually to a split between Hamas that took control of the Gaza Strip after Israel had withdrawn from that territory in 2013.

At the same time, the Israeli political map was changing, with the nationalist Likud Party forming coalitions with political parties representing the more radical Zionist camp and the Ultra-Orthodox community that oppose Israeli withdrawal from the West Bank as part of an eventual agreement with the Palestinians.

In short, the nationalist tide that was sweeping the world did not pass over Israel and Palestine.

Taking into consideration the growing challenges to U.S. hegemony in the Middle East in the aftermath of the Iraq War and the Arab Spring, it became clear that Washington was not in a position to launch a new Israeli-Palestinian peace process and that its diplomatic plans to advance the two-state solution needed to be placed on the policy backburner for a while.

Imagine One State for Two Peoples

As Yugoslavia was breaking up and the Middle East state system was about to collapse, the drive for national self-determination gained momentum in Scotland, Catalonia, the Basque region and even among the French speakers and Dutch speakers who were toying with the idea of partitioning Belgium. And with the more nationalist forces exerting more political influence in Israel and Palestine, this may have sounded to some like a perfect time for moving ahead with a new project: Establishing a bi-national state where Jews and Arabs would live together in peace and harmony until the end of times.

“In a world where nations and peoples increasingly intermingle and intermarry at will; where cultural and national impediments to communications have all but collapsed; where more and more of us have multiple elective identities and would feel falsely constrained if we had to answer to just one of them; in such a world Israel is truly an anachronism,” concluded the late historian Tony Judt, who in an article published in the New York Review of Books in 2003 all but dismissed the idea of an Israeli-Jewish State and by extension its mirror-image, a Palestinian-Arab one, joining the chorus of those advocating a one-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

As he explained it, the world was characterized today by a “clash of cultures” between “open, pluralist democracies and belligerently intolerant faith-driven ethno-states.” Israel, he warned, risked falling into the “wrong camp.”

Against the backdrop of stalled Israeli-Palestinian talks and the American failure to revive the peace process, the idea of Israelis and Palestinians opting to live together as citizens of the same state has been gaining more fans in recent years, especially among left-leaning peace activists who have argued that continued expansion of Jewish settlements has rendered the notion of an independent Palestinian homeland in the West Bank unworkable.

Indeed, Israeli and Palestinian intellectuals and some of their counterparts in the West in the have been embracing this new intellectual fad, One State for Two Peoples, the idea that Arabs and Jews could co-exist peacefully in a state occupying the area stretching from the Jordan to the Mediterranean Sea, and where Palestinians who are now living under Israeli military occupation would be able to gain legal and political rights as the new citizens of a single, democratic state.

Israeli and Palestinian academics and activists have launched the Association for One Democratic State in Palestine/Israel, noting that the proposed solutions to the conflict in Palestine/Israel have failed because they were “predicated upon a division of land that cannot be divided without creating further injustice.” The association was therefore convinced “that the creation of one democratic state is the only viable, long-term solution to the conflict.”

There are already the more than1.5 million Palestinian Arabs who live in Haifa, Lydia, Nazareth, and Um El Fahim who are Israeli citizens, who elect candidates to the Knesset (parliament) and enjoy other civil rights as well as about 250,000 Arabs in East Jerusalem who are residents of Israel but do not have Israeli citizenship.

So why not move ahead add to them the close to 4 million Palestinian Arabs who reside in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip and turn them into Israeli citizens, while allowing the 4.5 million Palestinian refugees living in the Middle East and elsewhere to return to the homes Jaffa or Haifa that they had lost in 1948? After all, Israel portrays itself as the “only democracy in the Middle East,” and all it would have to do now is to offer its Arab citizens basic civil rights as citizens of a democratic state.

The South Africa/Apartheid Analogy

In an article published in Egypt’s Al Ahram after the collapse of the Oslo peace process, the late Edward Said recalled his first visit to South Africa in May 1991, “[A] dark, wet, wintry period, when Apartheid still ruled,” although the African National Congress (ANC) and Nelson Mandela had been freed. “Ten years later I returned, this time to summer, in a democratic country in which Apartheid has been defeated, the ANC is in power, and a vigorous, contentious civil society is engaged in trying to complete the task of bringing equality and social justice to this still divided and economically troubled country,” Said wrote. A long-time opponent of the Oslo Agreement, he urged the Palestinians to “counteract Zionist exclusivity” by proposing “a solution to the conflict that, in Mandela’s phrase, would assert our common humanity as Jews and Arabs.”

Israeli Jews and Palestinian Arabs are locked in Sartre’s vision of hell, that of “other people.” But there is an escape. The solution, according to Said, was “Two people in one land. Or, equality for all. Or, one person one vote. Or, a common humanity asserted in a bi-national state.”

“One cannot unscramble an egg,” explained Diana Buttu, a Palestinian intellectual legal adviser to the Palestinian Liberation Organization, referring to the way the Israeli and the Palestinian populations are intermingled. The Palestinian leaders, she said, should give up their quest for an independent state and push instead for equal citizenship in Israel and “an anti-Apartheid campaign along the same lines as South Africa.”

The South Africa/Apartheid analogy is misplaced on many levels, including the underlying notion that the conflict between Israel Jews and Palestinian Arabs has been driven by the alleged racist ideological roots of Zionism that are compared to those of European settler movements. According to this narrative, the Palestinian Arabs are the indigenous population of the country while the Israeli Jews are foreign settlers not unlike South Africa’s white Afrikaners.

But then the in more ways than one, Zionism has proved to be one of the most successful national movements of the modern era. It not only gathered millions of Jews from around the world in their ancestral homeland and revived the Hebrew language, but it also helped turn a what was a backward third world country into one of first-class economy and a scientific and technological centre.

Moreover, the Israeli Jewish population includes non-white immigrants from the Middle East and North African countries, as well as from East Africa, in what turned to be for all practical purposes an exchange of population – Jews from Arab countries fled to Israel while Palestinian Arabs fled from that country to other Arab countries.

At the same time, the Palestinian Arabs are no more indigenous to the country than the Israeli Jews who live there today. They are members of clans and tribes that descend in large part from the Arab Muslim invaders that forced their religion and language on the country’s inhabitants, joined by emigrants from the surrounding Arab states who arrived there after WWI, driven not by nationalist feeling but by the employment opportunities and improved quality of life that accompanied Zionist immigration and land development.

Palestinians like Buttu are using the South Africa/Apartheid hoping to gain sympathy among liberal and left-leaning activists in Europe and the United States and will polarize Israeli society. In their fantasy, a campaign to bring an end to Zionism-Is-Apartheid would result in international pressure, including political and economic sanctions on Israel to provide full civil rights to the all the Palestinian Arabs, including those living in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, along the lines of the international campaign that helped bring an end to the Apartheid system in South Africa.

There is no doubt that the continuing Israeli military occupation of Palestinians is eroding support for Israel, especially among progressive groups in the West. But the political power of American Jews, the memories of the Holocaust, and the rising anti-Muslim sentiments in the West would allow even a nationalist Israeli government to continue expanding Jewish settlements, and eventually to overpower the Palestinians.

To put it differently, the South African conflict ended with the surrender of power by the defeated Afrikaners. There are no signs that Israeli-Jews are about the follow their example.

In fact, it is the Palestinian Arabs, unlike the blacks of South Africa who would become the main losers in the one-state utopian scheme. Such a state would only produce an explosive situation in which Jews would dominate the economy and most other aspects of the new state, creating a reality of exploitation. At that point in time, the state would become a new form of occupation that would only set the conflict on a more violent track.

The Post-Zionist Fantasy

Some left-leaning intellectuals in Israel and in the West, go beyond the South Africa/Apartheid analogy and compare the situation existing in Israel/Palestine today to the segregation era in the American South. They imagine that eradicating the Jewish identity of Israel in the same way that whites in Alabama and Mississippi had to give up their exclusive white identity, would allow Israelis and Palestinians to enter into a so-called Post-Zionist age.

Most demographers expect that under the one-state solution the Jewish population will fall to less than 40 percent by 2030. That assumes that granting of Israeli citizenship to Arabs in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip would create a situation where a majority of the citizens would choose to change the exclusive Jewish character of the state.

“So what?” respond the post-Zionists. Israel, like America in the 1960s, would go through a process of political liberalization both Jews and Arabs would recognize that all men and women, Jews and Arabs, are created equal and could coexist in the West Bank in the same way that whites and blacks co-exist in Alabama today. If an African American was elected as the President of the United States, we should welcome the possibility that an Arab would be elected as the Prime Minister of the new state.

Ironically, many of the liberals promoting the post-Zionist agenda and who also tend to be staunch advocates of religious freedom and women and gay rights seem to disregard the obvious: That in a state with a clear Arab majority, one would have to expect to see the growing influence of the kind of trends that pervade to one degree or another all the states in the Middle East, where the rights of religious minorities, women and gays are being threatened.

That a one-state solution would eventually result in the creation of a Palestinian Arab State, leading to the emigration of educated and liberal Jews from the country and to transformation of an advanced economy into another third world country, is being dismissed by Greater Israel advocates who are calling for the annexation of the West Bank to Israel. But in that case, the only way a Zionist government would be able to maintain the Jewish identity of the state is by denying citizenship to the residents of the West Bank, which will not be politically sustainable in the long run.

Utopia vs. Reality

The era of globalization and the Oslo Accord may have strengthened the influence of post-Zionist trends in Israeli society, especially in academia and the media, with leading intellectuals calling for the “normalization” of Israel as a secular Western nation by separating synagogue and state, modifying the Law of Return, and integrating the Arabs citizens into Israeli society. But these post-Zionists may not have noticed that there has been no sign of the emergence of a “post-Arabist” movement on the Palestinian Arab side, and if anything, radical anti-Western forces have been gaining more power in the Palestinian community.

Some Israelis and Palestinian frame their support for a one-state solution as realism in its most basic form: We need to recognize that the two-state solution is dead and that Jews and Arabs would have to share their common territory.

But what they are proposing is in itself an escape from reality. It is not only a reality in which bi-national and multinational arrangements are collapsing everywhere, but it also a reality in which, after 100 years of a clash between Zionism and Arab nationalism, there are no signs that the ideological forces driving these two movements have been exhausted.

If anything, those two secular nationalist movements seem to be taking more radical and atavistic forms that reflect their ethnic and religious sources. While radical Zionists seem to full, offensive swing and determined to settle and annex “Judea and Samaria,” on the Palestinian side, nationalism, including the Islamic version, is deepening and growing from martyr to martyr.

It takes real faith to believe that these two nationalistic peoples will give up the essence of their hopes and turn from total enmity to total peace, giving up their national narratives and being ready to live together as supra-national citizens. From that perspective, the one-state solution is akin to a utopia that is based on the vision that there is a perfect human being or that human beings can be perfected.

There is certainly no chance that the present Israeli generation, or its successor, will accept this solution, which conflicts absolutely with the ethos of Israel as it exists today. Nor are there any signs that Palestinian Arabs are ready for such an experiment.

Indeed, this is where the South Africa analogy breaks down, a point that should be appreciated by any expert in the study of power politics. The Afrikaners had lost the war over the control of South Africa and accepted their defeat. In the case of the conflict between Israelis and the Palestinians neither side is going to either win the war or raise the white flag anytime soon.

It does sound depressing. But both sides seem to be willing to pay the enormous costs involved in defending what they perceive to be their existential values and core interests and are counting on the support of powerful regional and global players.

Hence right analogy here is not South Africa but the wars of succession in the former Yugoslavia that concluded with very messy territorial compromises, which is probably what is going to happen in the case of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict at some point in the future.

At the same time, campaigning for the one-state utopia ends up diverting attention from the practical, immediate objectives of the Israelis and the Palestinians, at a time when the whole world has accepted the idea of two states for two peoples.

Let us assume for the sake of argument the one-state will emerge tomorrow in the form of Greater Palestine or a Greater Israel. If that happens, the Jews in Greater Palestine will end-up fighting for independence — which is exactly what the Arabs in Greater Israel are and will be doing until they win their independence, which could bring us …oops… back to square one: The need to divide the territory between two rival national communities: Israelis and Palestinians.