Diversity Debate

Don't Abandon the King Standard

How prevalent is it in our society, and what are its effects? How should our institutions attempt to dismantle it?

Over the past few years, but especially since Donald Trump’s election, we have witnessed a vanishing common ground on issues of race between Left and Right. Presently, the race debate in America is not over marginal issues or their nuances but over first principles; apart from a general (and correct) belief that racism is bad, few shared values bind people together. Instead, we have what Thomas Sowell once called, in a slightly different context, “a conflict of visions.” What is racism, and how should it be defined? How prevalent is it in our society, and what are its effects? How should our institutions attempt to dismantle it? On these and many other questions disagreement is fierce.

The media reaction to the recent episode, during which Trump was reported to have referred to Haiti and other African countries as “shitholes,” is indicative of widening disagreements about how we talk about race. Even in such an apparently straightforward case as this, a furious debate erupted over the proper way to interpret Trump’s remarks. On the Left, writers from Vox to the HuffPost condemned Trump’s as unambiguously racist. They argued that Trump not only implied that these countries themselves were dysfunctional, but that this dysfunction was reflected in the citizens of those countries. As German Lopez of Vox put it: “Trump is not just saying that Haiti and African countries are shitholes. He’s indicating that the (predominantly black) people from these countries are themselves bad — to the point that the US should not accept them as immigrants.” For leftists, moreover, Trump’s behavior was in keeping with a history of racism that must not be ignored.

Although some on the right largely concurred with this assessment, others came to the defense of the president. The editors of the National Review wrote, “What he was almost certainly trying to get at, in his typically confused way, is that we’d be better off with immigrants with higher skills.” In this reading, Trump’s comment was merely a tactical blunder, and not indicative of prejudice. Dennis Prager seconded this opinion, and said that Trump was right to point that 1) certain countries and societies are run disastrously and that 2) immigrants from those societies tend to use more welfare and are therefore more dependent on the American government. Trump’s language, Prager allowed, was inappropriate. But his general intuitions were correct.

The fundamental source of this and most other disagreements on race is that the Right and Left are applying different standards when they employ the word “racist.” The petty debates over whether this or that comment is racist will continue until some sort of consensus about standards can be reached. It would be more constructive, then, for political commentators to articulate the principles under which they are operating rather than presupposing them and accusing the other side of ill will when they happen to dissent.

The mainstream Right’s approach to racial issues is essentially guided by Martin Luther King’s dictum: judge others by the content of their character, not the color of their skin. So long as everyone is afforded equal opportunity without regard to race, the Right is mostly indifferent to outcomes. This is one of the reasons conservative commentators have rejected race-based affirmative action policies; preferential policies, they argue, make race important in processes where it should be irrelevant. David French of the National Review, for example, refers to affirmative action as “the new racism.”

Understanding the mainstream Right’s theoretical framework on race as informed by King’s dictum also explains the conservative position on ‘disparate impact’ issues — that is, issues where racial discrimination is presumed to exist because a supposedly colorblind policy has a disparate impact on members of a disadvantaged minority. Here again, conservatives are indifferent to statistical outcomes so long as the general approach and intent of a policy is not explicitly racist. Thomas Sowell, the Right’s most articulate spokesman on race, has argued against “disparate impact” claims as such: “The implicit assumption is that such statistics about particular outcomes would normally reflect the percentage of people in the population. But, no matter how plausible this might seem on the surface, it is seldom found in real life…” For Sowell, disparate impact is not evidence of discrimination because there is no reason to assume that there would be equal outcomes in the absence of discrimination.

On the other hand, much of the Left has abandoned King’s colorblind standard in favor of a sort of ‘active’ anti-racism. It should be noted that Martin Luther King’s views on affirmative action-like programs are disputed. What he would have thought about preferential policies, however, is less relevant here than is the perceived essence of his “I have a Dream Speech,” which has become part of the national conscience and has informed the defense of the colorblind standard. But colorblindness, many leftists argue, is insufficient. On its own it will not do enough to dismantle the remaining effects of white supremacy. If we are to finally eradicate racism, what is needed is an attitude and perspective that does take racial outcomes into account. Otherwise, blacks will continue to be mired in poverty, sent to prison at disproportionate rates, and under-represented in the nation’s top colleges and positions of power.

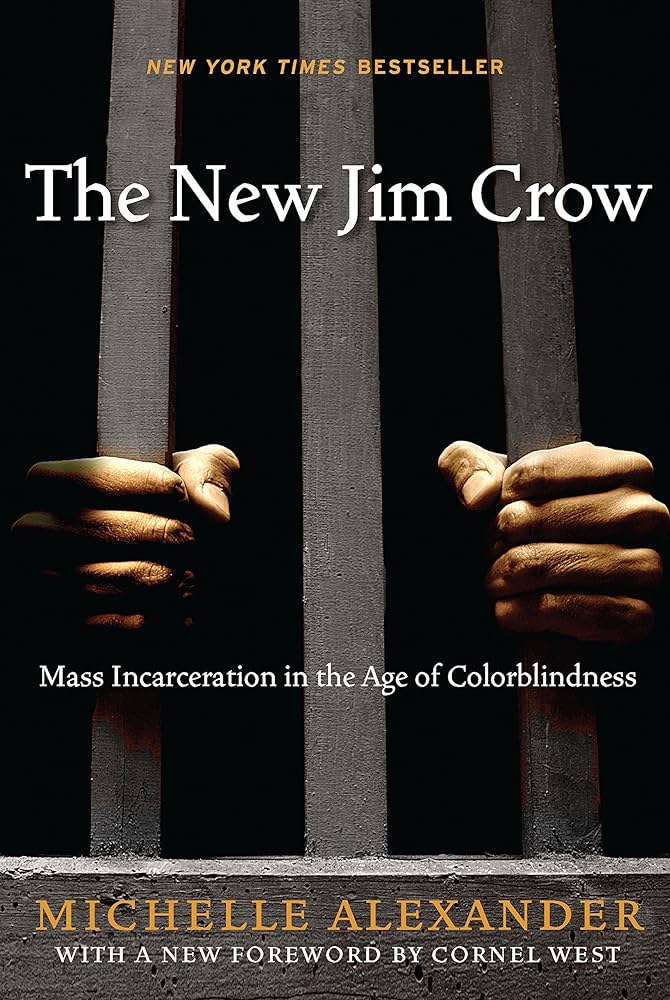

Such principles guided Michelle Alexander’s influential book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. Her thesis is that the U. S. criminal justice system has revitalized a racial caste system even as it presents itself as ‘colorblind.’ She writes: “In the era of colorblindness, it is no longer socially permissible to use race, explicitly, as a justification for discrimination, exclusion, and social contempt.” So, institutional racism circumvents this problem by labeling blacks felons, so that it can turn around and deny them the basic rights of citizenship that the old Jim Crow system once did.

Ta-Nehisi Coates of The Atlantic has made similar arguments in favor of an active anti-racism stance. In 2014 he went as far as to call the colorblind standard “elegant racism.” Elegant racism, he wrote, “is invisible, supple, and enduring. It disguises itself in the national vocabulary, avoids epithets and didacticism.” It manifests itself in the outrageous disparities between blacks and whites in terms of incarceration and poverty rates. It manifests itself in race-neutral language and policies that actually harm blacks. Even the term ‘mass incarceration,’ Coates argues, “obviates the fact that ‘mass incarceration’ is mostly localized in black neighborhoods” — blacks are targeted by police to an extent that dwarfs the comparable statistics for whites. Stamping out these and other forms of elegant racism, says Coates, will require a confrontation with history, a recognition that white supremacy persists, and a language and framework that tackles the continuing impacts of racism.

Coates and Alexander have gained wide audiences; their books are bestsellers, and they are celebrated across liberal media outlets. Their animating idea — that to overcome racism, the United States must discard any pretense to colorblindness — has become accepted across broad swathes of the mainstream Left. For better or worse, however, it marks a stark departure from King’s appeal that skin color should be ignored.

The battle between colorblindness and active anti-racism will have enormous consequences for American society. The questions asked, the policies pursued, and that language employed in racial discourse will all depend on the theoretical framework that defeats the alternative, or that gains wider acceptance. Affirmative action, police practices, and other programs will be decided by this debate over first principles.

Insofar as I’m prepared to weigh in on that debate in this essay, I want to argue that both empirical evidence and universalist moral principles still seem to corroborate Dr. King’s insights. What follows is not meant to serve as a definitive takedown of the active anti-racists’ stance, but as a series of objections to their approach, as well as a vindication of the continuing wisdom of colorblindness:

First, if it was correct to oppose Jim Crow and racial segregation because it is unjust to penalize people for characteristics like skin color over which they have no control, then one ought to oppose affirmative action and other such “color-conscious” policies on precisely the same grounds. The fact that it is now white and Asian students who are being disadvantaged as a result of systemically discriminatory policies, rather than black or Hispanic students, should have no bearing on the moral problem in question. Whatever the sins of (some) of their ancestors, it is unjust to expect higher standards from whites because of events for which they bear no personal responsibility; it is perhaps even more unjust to place higher standards on Asians, a group which, unlike whites, suffered from historical discrimination in the past. Affirmative action attempts to remedy a past, cosmic injustice through the infliction of present, concrete injustice. (And even at this task it likely fails.) The best solution is to judge applicants by the same standard when it comes to university admissions and job applications, and to implement policies that help everyone achieve high qualifications before they apply for those positions to begin with.

Second, attitudes toward, and interpretations of, inequalities and statistical disparities are important. If, as the active anti-racists assert, racial inequalities arise from differential treatment, then that problem would necessitate a particular set of policies. However, if racial inequalities originate in other factors, such as geography, culture, and age, then our attitudes toward statistical disparities must change accordingly. If the latter interpretation is true, there is no reason to assume that disparities are either suspicious or the result of structural injustices. Asian Americans, for instance, have lower unemployment rates than whites. Moreover, Asian American men earn 117 percent as much as white men. Presumably one could not appeal to structural injustices against whites to explain this gap — and if this point is granted, then the reasons we continue to see disparities between racial groups become clear without having to appeal to racism or discrimination. As Eileen Patten writes in her Pew report: “Research shows that a majority of each of these gaps can be explained by differences in education, labor force experience, occupation or industry and other measurable factors.”

Third, one of the most tenaciously-held assumptions of the active anti-racist stance is the notion that all particular statistics should, in some way, reflect general population statistics. This is why we see them decrying, among other things, the overrepresentation of blacks and Hispanics in prisons and the underrepresentation of these minorities in elite colleges. But in none of these particular cases is there any reason to expect the statistics to reflect demographics in the broader society. Rather, the correct comparison is the relevant pool from which those specific populations are drawn. It is more reasonable to expect the prison population to reflect the pool of people committing crimes and for the elite-college population to represent the pool of most qualified applicants. What would be fascinating, unprecedented, and strange would be a perfect demographic representation of the broader society across all areas, in spite of the relevant factors.

As the race debate rages on, the need to rediscover a set of unifying first principles will become increasingly important. Although King’s standard is now decades old, those who still long for a society where people are treated as individuals, rather than as members of (usually contrived) collectives must prepare themselves to defend and reaffirm the wisdom of colorblindness in the face of new ideological challenges.