Canada

The Dishonesty of #MeToo in Canada's Literary Scene

The effect of the #MeToo movement, especially in Canada, is creating the same subdued atmosphere among men.

When I was a less experienced teacher, I made a big mistake. Students were composing essays in a computer lab, and one young man thought he would be clever. Instead of writing, he spent his time shopping for an online essay. A flash of his parents’ gold card near the end of the class is what alerted me. He let his trick be known to the students around him and a bustle of barely repressed giggles and furtive looks ensued. When he came to the front of the class to hand it in, I handed it back and then pointed to the door. I said, loudly and firmly, “This is unacceptable and I’d like you to get out of my sight.” The class went silent and I was momentarily thrilled that I’d spoken so bluntly. However, I changed my mind when that silence persisted until the end of term. Without meaning to, I’d intimidated every other student in the room, none of whom, as far as I could tell, was cheating. I’d made classroom discussions difficult, and I had no one else to blame.

The effect of the #MeToo movement, especially in Canada, is creating the same subdued atmosphere among men. Most support women and are, like my class, already behaving like reasonable human beings. Even so, their support isn’t helping and this week yet another politician was forced to step down over an allegation that barely rose to the level of a bad date. Since it’s clear prominent men, journalists included, cannot safely criticize the movement, prominent women of all political stripes are doing so instead. Rosie DiManno of the Toronto Star, commenting on Brown’s anonymous accusers states: “It is not brave to speak from the shadows. It is not courageous to vilify anybody from within bubble-wrapped camouflage.” Christie Blatchford in the National Post asserts the scandal “means that every man in the world is vulnerable, not because he has necessarily misconducted himself, but because a woman may say he has.” Even Margaret Atwood, renowned feminist and literary star, expressed concern. However, by simply signing a letter demanding due process be followed in the case of novelist Steven Galloway (see below), she too incurred the wrath of the #MeToo mob. Ditto the second most recognizable signatory of the letter, Joseph Boyden. He’s a prize-winning author who writes about indigenous themes. To punish him, leftist critics have questioned his indigenous lineage and accused him of cultural appropriation.

While the misery has spread far and wide, the literary scene in Canada seems to be a fault-line of sorts, with quakes hitting the literati of Vancouver and Montreal. The creative writing program at the University of British Columbia was the first to implode in 2015, with the revelation that Galloway, its chairperson, had been accused of sexual assault, an accusation that was later dismissed by an independent investigator, retired judge Mary Ellen Boyd. The latest seismic shift has happened at Concordia University in Montreal. Its creative writing program has imploded similarly, with two male professors being relieved of teaching duties after multiple accusations of sexual harassment. It’s yet another #MeToo moment, complete with tearful media interviews and statements from women who claim numerous careers have been ruined.

I see two issues worth addressing. First is the powerful implication that only women can be harassed. Second is that all parties’ desires, especially in the case of historical accusations, should be understood in the context of their competitive environments.

The #MeToo narrative is simple: men are aggressive, abuse is pervasive, and women are harassed with shocking frequency. It’s a too-bad-to-be-true premise that rouses the skeptic in me: in my decades of working life, I’ve never witnessed the level of abuse the campaigners assert is happening. I’ve seen plenty of sexual couplings, but almost all were consensual with an equal number of men and women acting badly when they weren’t. So in lieu of any countervailing (and publicly acknowledged) narratives, I’ll put forth some of my own.

- Throughout my teaching career, I’ve worked alongside two male colleagues who were especially attractive. They too could complain of harassment since they routinely fended off female students, many of whom visited them during their office hours whether they needed help or not. I watched as these colleagues went from affable to arctic in a second when they saw these dreamy-eyed students coming.

- I’ve also known two colleagues who were falsely accused of sexual impropriety with students. Luckily, both were exonerated. In the first instance, the accuser’s family contacted the school’s administrators and reported that their daughter had psychiatric problems and habitually made false accusations; in the second, a petite and quiet colleague, working behind a large filing cabinet, overheard a female undergrad threaten a teaching assistant with a rape accusation. The student wanted the teaching assistant to meet her off-campus.

- A Concordia alum said of the current kerfuffle: “Even if the most attractive student comes into your office and takes off all his clothes, the onus is on the professor to say no, because they’re the adult, they’re the professional, they’re the person in a power position.” This sounds simple, but professors experience it differently. In the early 90s, this happened to a colleague who was in his 40s: a 19 year-old student came to his office wearing only a raincoat that she promptly removed after closing the door. He demanded that she get dressed and then demanded that she leave. He’d acted correctly and decisively, but was still concerned about reporting it. He feared two things: reprisal and the possibility he wouldn’t be believed.

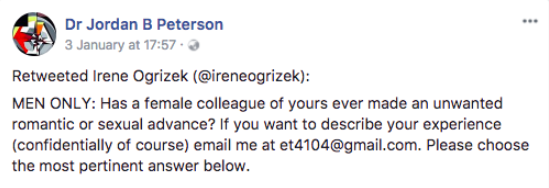

These may be one-off anecdotes, but an online survey I conducted in January supports the theory that women often pursue men in the workplace. 15,348 men responded to the following question:

While a self-selecting survey always has its limitations, 49% of men said yes; 37% said no, and 14% said they had witnessed it happening. It seems reasonable to conclude that men are at least sometimes targets of sexual advances in the workplace.

While the survey used the word “unwanted” to describe the advances, many men said the advances were welcome. In fact, a number said they had married the women who made them, while others said the advances were flattering, even though they went nowhere. Another group of men made it clear they did not experience the advances as threatening (as they believed a woman might), and yet another group reported women who became obsessed with them, with several saying they had been fired after spurning their putative lovers. There was one final niche group, composed of performing musicians, who told stories of being kissed, groped and stalked by women who waited for them backstage after performances.

The points made by the survey and the anecdotes are clear: we women in the West have a high degree of agency and the capacity to be abusive too. Our next task is to admit we don’t always compete fairly.

The fact is that talent can grow anywhere and not all writers need creative writing programs to succeed. Here’s a hypothetical career path: a young woman living in Sudbury, a northern Canadian town, attends her local university because she can’t afford to go elsewhere. Instead of studying creative writing, she studies literature and supplements her major with a variety of electives, all of which enrich her capacity for understanding the world. After she graduates, she takes on an administrative job at a local company and commits to writing 500 words a day towards her first serious novel. She spends each weekend revising.

When she finishes, she might ask her former professors for help. If she’s lucky, one will read it and give her useful feedback. If she’s less lucky, which is more likely, all will decline. She sends the manuscript off to publishers regardless. She believes in her work because she should: the young woman is genuinely talented.

Here’s where my sympathy for the creative writing students at UBC and Concordia ends. Students in these programs are given opportunities to deepen their knowledge of literature and hone their writing skills, processes that in theory should constitute 100% of their tuition fees. However, it’s also true that through their professors, they make valuable contacts in the publishing world and cultivate friendships with more established writers. Apart from university and college co-op programs, this is exceptional. Undergraduates do rely on professors for references when they apply to grad school, but for those who choose to end their studies, they are on their own when it comes to the employment market. That is, professors do not, as a rule, introduce students with bachelor degrees to potential employers.

It’s this unearned privilege, rarely questioned, that creates two imbalances of power, one in the department, where professors barter with the promise of success, and one in the context of Canadian literature generally. The latter is especially consequential when we consider the manuscript written by that young woman in Sudbury. Will it go into the same pile as manuscripts endorsed by UBC or Concordia professors? Will it be read by a junior editor with little power or by a senior editor with plenty? What if the young woman’s plot included a female character whose flirtation with evangelical Christianity improved her life? Or what if she submitted a moving memoir about her disillusionment with feminism? Are beautifully written texts that subvert politically correct ideas still being published? Is that even a question worth asking?

Here’s what two graduates of the Concordia program say they experienced:

Ibi Kaslik, a Toronto-based New York Times bestselling author, said a professor had made repeated unwanted romantic overtures towards her that began on her first day in his class. She said it culminated in a meeting where her professor made her come to an off-campus location, where he pretended she was his girlfriend in front of colleagues.

Professor Allen did help [Heather] O’Neill publish her first manuscript…but to this day, she does not include it on her list of published work. “I have never been able to feel pride about it because it resulted in the sexual harassment,” she said. “It just undermines your own sense of yourself as an intellectual and an artist, that you’re suddenly objectified.”

This might not be a good time to make a sweeping generalization, but in my experience, men are more realistic about the catches that come with unsolicited help. For many, quid pro quo agreements are entered into willingly, are negotiated or are rejected out of hand. These women have successful writing careers despite their experiences at Concordia. Only one former student has said blacklisting existed, an assertion that suggests there are no sympathetic women in Canadian publishing. I’m not condoning the behaviour of the men or saying they didn’t abuse their powers. What I am saying, instead, is that the situations were apparently manageable since these women did manage. When Heather O’Neill acknowledged that only students who socialized with professors got published, it’s clear she understood the bartering system and proceeded regardless. As we all know, the biggest hurdle for writers is getting their first work out there. Like or not, these oversexed professors delivered.

On the other hand, that young woman in Sudbury is still waiting for feedback—any feedback—six months later. Her unleveraged position deserves some weight in this discussion. O’Neill suggests that outlawing relationships between professors and students would protect students, a solution that clearly misses the mark when it comes to rebellious writers and forbidden fruit. A better idea would be to remove the carrot at the end of the stick. End those relationships between the universities and publishers and let students in creative writing programs make their own way just like other writers. In other words, removing the option of purchasing clout, however it’s sold, will make the system genuinely fairer.

As an undergraduate, I too had a professor who concocted stories to get me alone. Using prevarication and flattery, I was finessing my way around him when I was forced to drop the course. A fellow student I trusted had gone to his office and repeated some of the complaints I’d made about him. She was competitive about grades so I suspect she did it to curry favour. When he summoned me to his office and spat my words back at me, I knew I was a goner.

We need to admit we’re competitive and learn to handle it better. To not retreat from the discomforts of competition by using inflated beliefs about male privilege or damsel-in-distress stories that gloss over strategies we use to gain advantage. Moreover, if many men say they have experienced women’s advances at work, it’s clear some of us are behaving badly too. Feminists complain about a #MeToo backlash, and complain about dissidents like me, but it’s the dishonesty of the movement that makes it simply unsupportable.