Books

Buy Banned Books

In our hyper-mediated, panoptical culture, where neurotic self-reference is now almost completely inescapable, the continuing contribution of imaginative fiction and investigative journalism has never been more necessary.

What is lost when we insist that literature be ‘authentic’ and that some portrayals – even journalistic narratives – may only be authored by their real life counterparts? If the latter half of the 20th century witnessed the death of the author, then the social media age hails its return as a mutant zombie. Increasingly, we are living in a time in which the written word not only cannot stand on its own merits, it must not. If this sounds alarmist, consider one of the recent controversies surrounding the question of who should be allowed to write what. While it follows an increasingly familiar and depressing pattern, the incident also represents a Rubicon-crossing moment in social media age censorship.

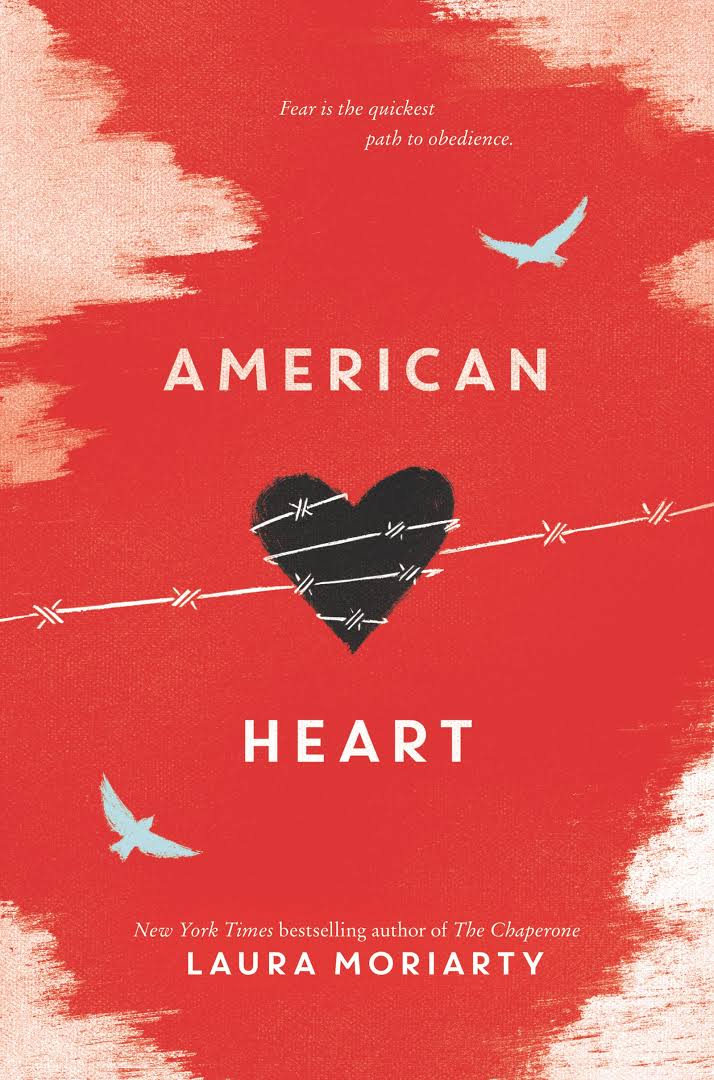

The book in question is an American YA (Young Adult) novel entitled American Heart, and the author is a white, non-Muslim named Laura Moriarty. Released this week, the story portrays a dystopian future America in which Muslims are being rounded up and thrown into detention centres. Within this nightmare is the Huckleberry-esque journey of a 15-year-old white Midwestern girl out of blinkered nationalism, as she comes to terms with the racism around her, and eventually travels with an Iranian-American companion to the Canadian border. As the title suggests, it appears to be a fable about the battle for the soul of Middle America.

In preparing the book, Moriarty was incredibly diligent, avidly researching Iranian culture and running the manuscript by two Iranian-American friends, a Pakistani-American practising Muslim, and a black colleague with a lot of experience in critiquing ‘white saviour narratives.’ The publisher then put the novel through a further round of ‘sensitivity reads,’ during which readers from the corresponding minority group are tasked with combing through the work for things that might be deemed offensive or ‘problematic.’ In the first instance, it seemed as though her painstaking deference had paid off. Late last year, Kirkus, the hugely influential industry magazine that reads books months ahead of publication, passed the novel to a Muslim-American reviewer who assessed it enthusiastically, awarding it a coveted Kirkus star. When the ‘culture cops’ got wind of this, all hell broke loose.

Diatribes promptly appeared on Goodreads beginning “fuck your white savior narratives.” A Book Riot article instructed its readers which novels to buy instead of American Heart, “a book that exploits Muslims” and which the unwary should apparently avoid lest they catch Islamophobia. The inevitable expletive-filled pile-ons erupted on Twitter. At this point, it is worth bearing in mind that very few of these splenetic internet warriors could have read American Heart, because the book isn’t published until this week. But in the Twittersphere, this is not the strangest thing or perhaps even strange at all. These storms increasingly erupt when any white writer, living in a multicultural society, dares to write a character outside their ethnic group.

More chilling is what Kirkus did next. First, the editor-in-chief posted an apology which effectively threw both Moriarty and Kirkus‘s own reviewer under the bus. “[S]ome of the wording,” it said of its own review, “fell short of meeting our standards for clarity and sensitivity, and we failed to make the thoughtful edits our readers deserve.” Kirkus then retracted the review and rewrote it to include admonishment of the novel’s ‘problematic’ portrayal of a Muslim character through the eyes of a white girl (a device originally praised by the Muslim-American reviewer for being “an effective world-building device”). Finally, to be extra safe, Kirkus stripped the book of its prized star.

There is a saying in North Korea, the fist is closer than the law, warning those who misbehave that citizen retribution often travels faster than the authorities can. In 2012, after a 19-year-old man was arrested for burning a poppy, the Guardian‘s Ally Fogg wrote: “The new tyrant is not an oligarch or a chief of secret police, but an amorphous, self-righteous tide of populist opinion that demands conformity to a strict set of moral values. What we are seeing has less to do with the iron heel than with the pitchfork.” The term ‘banned books’ may seem a bit outdated in the 21st century West. Perhaps ‘backed down on books’ would be more fitting (if less catchy). But the phenomenon has the same effect – intimidation, silence, conformity, and artistic straitjacketing.

Of course, the woke among us will shrug and say that Laura Moriarity should check her (white) privilege. Alas, such people suffer from hubris and fail to realise that, in the end, this identity puritanism will come for everyone – yes, even black and minority ethnic writers. Demanding that art be ‘native’ has a way of fetishizing minority artists and ghettoising them to stay within their respective lanes as well. But – probably more pressingly for the culture cops – if the acceptable range of representation continues to narrow, the time will come when some of the most talented writers around, BAME writers who are middle class (as many of them are) and/or privately educated, will no longer be allowed to ‘appropriate’ the experiences of black people of more humble means (as they frequently do). If we are to follow this fashionable train of thought, what gave Marlon James, who wrote the brilliant Booker Prize-winning A Brief History of Seven Killings, the right to portray shanty town kids when he’s the middle class son of a police detective?

We often call this a ‘cultural appropriation’ panic, but the animus driving it is reaching into the deepest crevices of writers’ private lives and personal histories. I call this the memoirification of literature; the lovechild of a justifiable call for more diverse writers and a social media marketing imperative, this drive to personal confession demands ever more particularised voices prepared to share their particularised testimonies under the banner of literary forms that are not, by definition, supposed to be testimony. And increasingly there are penalties for those who appear not to ‘stay in their lane’ and write endlessly about themselves.

There is no appeasing this impulse. In the last few weeks, I read an article asking who ‘gets’ to write fiction about sexual abuse and another telling writers how they must do so should they dare. The current zeitgeist for biographical vampirism is even pushing journalists reporting on issues of public interest to qualify themselves. As James Bloodworth recently put it, having fielded online jibes for writing a reportage book about low wage labour in Britain while not actually being (or no longer being, in his case) a low-wage labourer: “A peculiar thing about our age is that one of the easiest ways to get ahead is to talk endlessly about yourself. If you aren’t prepared to emote publicly about how ‘tough’ things were for you personally, you’re effectively at a disadvantage to those that are.” Were his critics not sure what journalism is?

For those of us that have memoir-worthy backstories but are more memoir-averse, this trial-by-testimony approach to choosing and marketing literature is alarming. As it happens, I fit within several historically ‘spoken for’ and much written about groups. However I don’t write testimony and I do not own these issues. There isn’t one way to emerge from adversity, so demanding a paint-by-numbers approach to its portrayal is frankly childish, reductive, and philistine. Characters should be three-dimensional beings, not mascots commissioned by committee.

Twenty years ago, upon the release of Anne Michaels’ acclaimed novel Fugitive Pieces – a story of Jewish displacement and generational trauma post-World War II – the author famously refused to reveal whether she herself is Jewish. Michaels believed that fiction should speak for itself, insisting even in 2009 that:

We should all be interested, no matter where we come from, or who our parents are. It’s not my province; it’s ours. These questions concern us all…With that book, I was asked am I Jewish, am I Catholic, am I Greek…And, yes, I did resist answering, because I really feel that to answer would be a cop-out…It would diminish the enterprise. Because, you know, it’s not about me. You spend your time when you’re writing erasing yourself. The idea is to get out of the way of it.

Just eight years later, Michaels’s comments sound like heresy. I can’t erase myself, and neither can you, the identitarian replies.

In the literary world, as in politics and the humanities, marginalised people have, rightly, demanded that their voices be heard. This is a good thing, and these days anyone with even a cursory acquaintance with the sphere of publishing would know that previously underrepresented voices are not just being ‘given space,’ they are actively sought out. Great. What is not great, however, is assessing a piece of literature’s right to exist on the basis of the author’s skin pigmentation, gender identity, or biography, or employing these categorisations as proxy for an analysis of the work’s actual artistic merit. Have we forgotten that the imaginative process involved in fiction used to be valued for its own sake, embodying an aesthetic and moral ambition (for both writer and reader) to reach beyond the narcissism and self-interest that tend to afflict human beings?

No one can deny the significance of the testimony of the heretofore unheard, and how important it is for the rest of the world to listen. But this insatiable demand for strictly testimonial fiction and even journalism reflects a misplaced faith in the integrity of the memoir form itself. As our social world becomes ever more mediated and constructed, the notion of perfect authenticity has become a Loch Ness monster; often searched for, rarely (never?) seen. Many astute and talented memoirists would, I’m sure, concur. Published self-revelation is as much about what the writer omits as it is about what they include. Nabokov put it beautifully in his own Speak, Memory when he reflected on the trouble that can arise when an author inserts themselves into the text:

His true purpose here is to project himself, or at least his most treasured self, into the picture he paints. One is reminded of those problems of “objectivity” that the philosophy of science brings up. An observer makes a detailed picture of the whole universe but when he has finished he realises that it still lacks something: his own self. So he puts himself in it too. But again a “self” remains outside and so forth, in an endless sequence of projections, like those advertisements that depict a girl holding a picture of herself holding a picture of herself holding a picture that only coarse printing prevents one’s eye from making out.

Narcissism and self-deception exist. Everyone suffers them to some degree. Yes, even the oppressed. One of the only defences we have against these things is a collective resistance to what therapists call ‘no talk rules.’ This is why we must buy the new banned books. As the (young, gay, black) writer Ryan Douglass recently asserted: “The harm of callout culture is quietly dripping into PoC communities and making us afraid of our own narratives.” Indeed, autobiographical fiction tends to contain similar potential pitfalls to memoir, because a writer composes it in the knowledge that they will be quizzed about all of it; it is built into the marketing strategy.

And here we come to an inconvenient point for the ‘woke’: the trend towards identity puritanism in literature is not only being driven by an increasingly right-on publishing cohort, but by an economic model ever more reliant on social media (testimony, personalisation, first-person singular). One needn’t be a Marxist to appreciate the wisdom of critics who have argued for an analysis of the way literary genres have perhaps, in the words of James Dawes, “emerg(ed) as ideological practices for producing subjects consistent with broad economic and cultural transitions.” Is what many imagine to be a radical reshifting of voices, also a compliant cultural extension of tech-dominated capitalism, and the inevitable progeny of selfie culture? Today, activism is a key strand of the marketing strategy of big brands, from soda companies to supermarkets. And in the new activism culture, words are violence. Ergo, ‘calling out’ so-called problematic portrayals acts as substitute for real world action against the atrocities that these offending portrayals depict or warn of. But for all the ardency of call-out culture, not one profanity-strewn American Heart tirade will close Guantanamo Bay or reform a broken prison system.

What the author Lionel Shriver has called “a kind of fictional apartheid” harms both art and politics. In our hyper-mediated, panoptical culture, where neurotic self-reference is now almost completely inescapable, the continuing contribution of imaginative fiction and investigative journalism has never been more necessary. Increasingly, these are the social media age’s banned books. And those of us who are against what literary Nobel Laureate (and cultural appropriator) Kazuo Ishiguro calls “the imagination police,” have a duty to buy them. With that, my copy of American Heart beckons.