How the Politics of the Left Lost Its Way

One important – and overlooked – effect was how it changed the idea of the term “Left” in political terminology.

One hundred years ago, the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia and set up the first long-lasting Marxist government. The Russian Revolution’s impact was wide-ranging. One important – and overlooked – effect was how it changed the idea of the term “Left” in political terminology. Following the Bolshevik takeover, the term Left became more strongly associated with collectivism and public ownership.

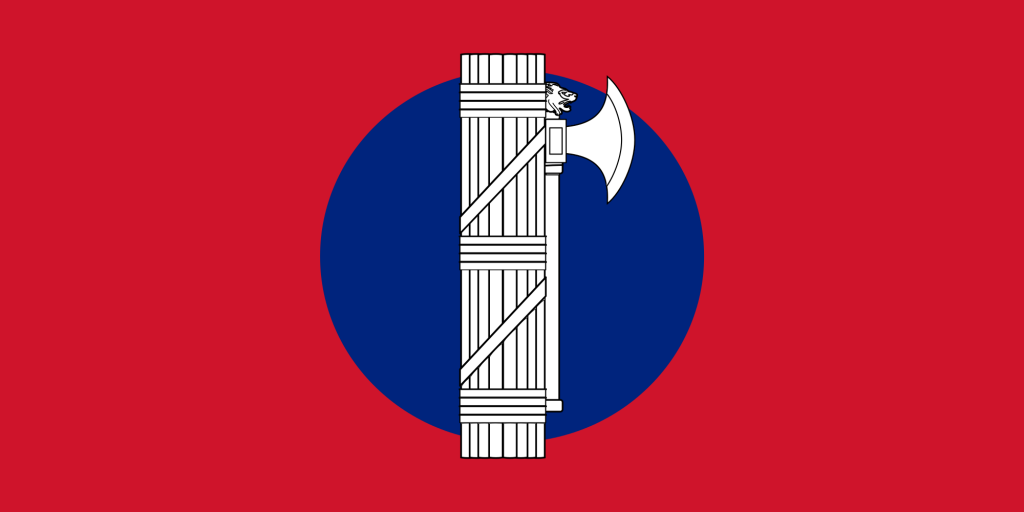

But originally the term Left meant something quite different. Indeed, collectivism or public ownership are not exclusive to the Left. The word fascism derives from the fasces symbol of Ancient Rome, a bundle of rods containing an axe, which signify collective strength.

Another effect of 1917 was to undermine further the democratic credentials of the Left. These had already been undermined by early socialists such as Robert Owen, who had been opposed to democracy. After Soviet Russia and Mao’s China, part of the Left was linked to totalitarian regimes with human rights abuses, execution without trial, little freedom of expression and arbitrary confiscation of property.

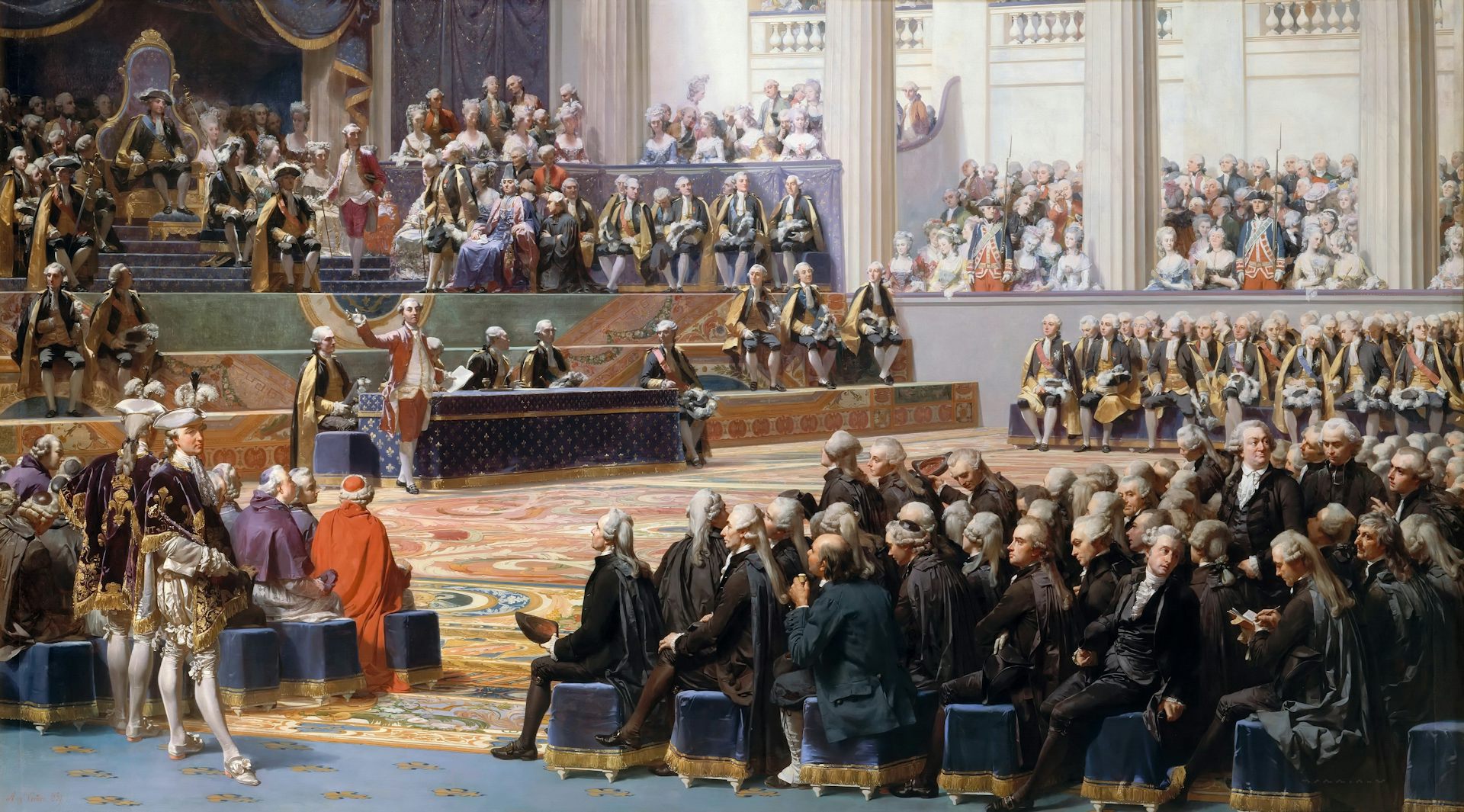

Origins of Left and Right

The political terms Left and Right originated in the French Revolution. In 1789, in the National Constituent Assembly, deputies most critical of the monarchy began to gather on the seats to the left of the president’s chair. Conservative supporters of the aristocracy and the monarchy congregated on the right side.

Those on the right wished to maintain the authority of the crown by means of a royal veto, to preserve some rights of the aristocracy, to have an unelected upper house, and to maintain major property and tax qualifications for voting.

Those on the left wished to limit the powers of the monarchy and to create a democratic republic. They demanded an end to aristocratic privileges and limitations to the powers of the church and the state.

Hence Left originally meant liberty, human rights, and equality under the law. It meant opposition to monarchy, aristocracy, theocracy, state monopolies, and other institutionalised privileges. The original Left opposed justifications of authority derived from religion or from noble birth. It supported democracy and private enterprise.

Ostensibly, the Left has always stood for equality. But what does this mean? Does it mean equality under the law? Such equality was explicitly denied by Karl Marx and his followers, who argued that after the revolution the bourgeois class should be denied legal rights. This was put into practice after the revolution in Russia in 1917.

The pursuit of equality is not confined to socialists. Liberals such as Thomas Paine and John Stuart Mill promoted the more equal distribution of income and wealth, as well as equality under the law. Liberals favour markets and private property, partly because they help protect individual autonomy. So can liberals be described as Left? Today’s Left has become so widely associated with public ownership that it would not include radical liberals in its broad movement.

The term Right has also shifted in meaning, from nationalist and traditionalist apologies for the privileges of aristocracy, to greater advocacy of free markets and private ownership, which ironically had been the territory of the original Left of 1789.

Wrong turnings?

The Marxist government in Russia quickly evolved into a one-party state. A regime of purges and terror ensued. I argue in my book Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost that a slide towards totalitarianism is inevitable within Marxism. This is because the Marxist concept of class struggle and its proposal for a proletarian government undermines the notion of universal human rights, developed in the Enlightenment and proclaimed in the French Revolution.

By the 1970s some on the Left went further, to oppose any export of Western ideas, and to reject any notion that poorer countries deserved to enjoy the same human rights that were promoted in Europe and North America. Proposals to extend these rights or values were seen as apologies for “Western imperialism”. And, in their enthusiasm for “anti-imperialist struggles” many on the Left supported terrorists and religious extremists, including the IRA, Hamas, Hezbollah and the regime in Iran. This is far from the views of the original Left.

Of course, people that consider themselves as Left-leaning are not obliged to follow the ideas of the original Left. But it is important to understand how strains of Left thinking have twisted and turned from their original source. And recognise that alternatives are possible – particularly when the language of politics today is so broken. George Orwell wrote in 1946:

One … ought to recognise that the present political chaos is connected with the decay of language, and that one can probably bring about some improvement by starting at the verbal end.

The term Left has gone through major changes of meaning in the last two centuries. With this decay there has been a large degree of chaos. Meanwhile parties on the Left around the world are in crisis as a result of ideological fragmentation. If we are to have progressive change in society we need to first reconfigure the political map and no longer be restricted by what has come to define Left and Right.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.