Human Rights

Does Female Genital Mutilation Have Health Benefits? The Problem with Medicalizing Morality

The mantra implies that if FGM did have health benefits, it wouldn’t be so bad after all.

Four members of the Dawoodi Bohra sect of Islam living in Detroit, Michigan have recently been indicted on charges of female genital mutilation (FGM). This is the first time the US government has prosecuted an “FGM” case since a federal law was passed in 1996. The world is watching to see how the case turns out.

A lot is at stake here. Multiculturalism, religious freedom, the limits of tolerance; the scope of children’s—and minority group—rights; the credibility of scientific research; even the very concept of “harm.”

To see how these pieces fit together, I need to describe the alleged crime.

The term “FGM” is likely to bring to mind the most severe forms of female genital cutting, such as clitoridectomy or infibulation (partial sewing up of the vaginal opening). But the World Health Organization (WHO) actually recognizes four main categories of FGM, covering dozens of different procedures.

One of the more “minor” forms is called a “ritual nick.” This practice, which I have argued elsewhere should not be performed on children, involves pricking the foreskin or “hood” of the clitoris to release a drop of blood.

Healthy tissue is not typically removed by this procedure, which is often done by trained clinicians in the communities where it is common. Long-term adverse health consequences are believed to be rare.

Here is why this matters. Initial, albeit conflicting reports suggest that the Dawoodi Bohra engage in this, or a similar, more limited form of female genital cutting – not the more extreme forms that are often highlighted in the Western media. This fact alone will make things rather complicated for the prosecution.

The defense team has already signaled that it will emphasize the “low-risk” aspect of the alleged cutting, claiming that it shouldn’t really count as mutilation. It is, after all, far less invasive than Jewish ritual male circumcision, which is legally allowed on minors in the US, no questions asked.

Based on this discrepancy, if attorneys for the Bohra can show a gendered or religious double standard in existing law, the ramifications will be not be small. Either male circumcision will have to be restricted in some way, or “minor” forms of FGM permitted. The outcome either way will be explosive.

I will dig into the male-female comparison—and explore its legal implications—later on. But the law will not actually be my main focus. Instead, what I’ll suggest in this piece is that the question of health consequences, whether positive or negative, should not exhaust the ethical analysis of these procedures.

There is more to “good” and “bad” than healthy versus unhealthy.

In fact, as the Bohra case will show, there are serious, even dangerous downsides to medicalizing moral reasoning – and to moralizing medical research. On both counts, I argue, at least when it comes to childhood genital cutting, apparently biased policies from the WHO are making things a great deal worse.

“The tendency today is to roll over and ‘scientify’ everything,” says Julian Savulescu, a philosopher at the University of Oxford. He goes on: “Evidence will tell us what to do, people believe.” But people are getting it wrong. When you reduce your ethical analysis to benefit-risk ratios, you miss important questions of value.

Take the ritual nick, or male circumcision for that matter, and ask yourself what might be morally problematic about these customs if putting medical benefits and risks to one side. A few possibilities come to mind.

First, the perceived need to cut children’s genitals—whatever their sex or gender, and however severe the cutting—as a precondition for accepting them into a community should plausibly be questioned, rather than taken for granted.

Part of the reason for this is that, regardless of health consequences, many individuals whose genitals were cut when they were children grow up to feel disturbed by what they take to be an intimate violation carried out when they were too young to understand or refuse.

That prospect alone should weigh heavily in parents’ minds when contemplating these sorts of practices. The genitals are not like other parts of the body. People assign different meanings to having their “private parts” cut or altered, and they do not always appreciate, much less value or endorse, the intentions of the ones who did the cutting.

For example, realizing that they needed to be “marked” or “purified”—that they were not seen as perfect the way they were born—can be hard to swallow for many “cut” individuals, even if no tissue is removed. A person can always undergo a genital procedure later on in life, if that is what they want. But those who resent being cut cannot “undo” what has happened.

There is also the possibility of psychological harm, over and above the issue of contested “meanings.” Although it is hard to measure scientifically, such harm undoubtedly varies with the mental and emotional disposition of the child and the timing and circumstances of the cutting.

Some Bohra women, for example, report feeling emotionally traumatized by what happened to them when they were little girls—the confusion, the pain, the embarrassment of being held down with their genitals exposed—while others insist that they didn’t mind, and are proud of being cut. (Similar ambivalence can be found among religiously circumcised men.)

Both kinds of testimony should be taken seriously. Yet those who claim there is no harm in “mild” forms of childhood genital cutting often ignore such individual differences. Instead, they point to vague, impersonal averages or talk in abstract, theoretical terms.

Not uncommonly, they claim to be speaking on behalf of their entire religious community, as though it were a monolith (at least with respect to attitudes about cutting). Meanwhile, dissenters from within the community are often ridiculed, waived away, or simply silenced: those who speak out may be faced with “excommunication and social boycott.”

The power of tradition to smother resistance can be intense.

All of that said, even if “health consequences” were the only thing that mattered morally, the fact that a given act of cutting is less severe than some alternative does not eliminate the need for concern. This is because any time a sharp object is brought into contact with sensitive flesh, it poses some risk of physical harm, however small.

The knife could slip. Nerve damage could occur. Bleeding or infections could ensue. And while those factors might not be ethically decisive for more “neutral” parts of the body—even ear-piercing and cosmetic orthodontics carry risks—a person might reasonably conclude that any chance of adverse outcomes is too great when it comes to their sexual organs.

Finally, if health consequences in the form of “health benefits” are seen as legitimizing childhood genital cutting—as is often suggested in the case of male circumcision—then proponents of female genital cutting (FGC) who are loath to give up their valued custom might be motivated to find such benefits in order to appease their critics.

They might even succeed in doing so. For reasons I will get into later, it is not actually implausible that certain “mild” forms of FGC, such as neonatal labiaplasty, could reduce the risk of various diseases.

But that wouldn’t make the cutting a good idea. Instead, I will argue that children should be free to grow up with their genitals intact—no nicks, cuts, or removal of tissue—even if the risk of adverse health consequences turns out to be mild, and even if certain health benefits can be found.

What about the legal issues? I can’t say too much about the particulars of the forthcoming trial because I don’t want to prejudice the outcome, but I can make some general observations.

To be frank, the US government has probably picked the worst possible case to show it is “serious” about addressing FGM. It is setting itself up for plausible accusations of anti-Muslim bias, as well as sexist double standards (as I hinted at before).

The main reason for this is as follows. If convicted, the Muslim minority defendants face 10 years to life in prison for allegedly practicing a form of FGM that is less physically invasive than other forms of medically unnecessary genital cutting that are legally tolerated in Western countries.

I have already mentioned male circumcision. There is also intersex genital “normalization” surgery (which has been brilliantly discussed in this context by Nancy Ehrenreich); supposedly virginity-signaling hymen “repair” surgeries (which I have written about elsewhere); and at least some so-called “cosmetic” female genital operations, which are increasingly being carried out on minors.

I promised I would tackle the male-female comparison, so let’s look at male circumcision (some details are needed to spotlight the inconsistencies, but I hope you will bear with me). Unlike the “ritual nick,” which does not typically alter the form or function the external (female) genitalia, male circumcision permanently alters both.

To begin with, it—by definition—removes most or all of the foreskin, which is about 50 square centimeters of elastic tissue in the adult organ and the most sensitive part of the penis to light touch.

It creates a ring of scar tissue around the shaft that is often discolored.

It makes sexual activities that involve manipulation of the foreskin—see here for a NSFW video—impossible. And it exposes the head of the penis, naturally an internal organ, to rubbing against clothing, which can cause chafing and irritation.

Those are the guaranteed effects. Possible “side effects” include painful erections if too much skin is removed (the penis is very small at birth and the choice of where to cut is essentially a guess), partial amputation of the glans due to surgical error, infections, cysts, fistulas, adhesions, pathological narrowing of the urinary opening, severe blood loss, and rarely—except in tribal settings where it is common—death.

Yet it is perfectly legal in the United States to perform a circumcision on a male child for any reason. Religion, culture, parental preference—regardless of the motivation, the cutting is tolerated, and you don’t need a medical license to do it.

In fact, even ultra-Orthodox Jews who perform an unhygienic “oral suction” form of circumcision, in which the circumciser takes the boy’s penis into his mouth and sucks the wound to staunch the bleeding, are legally permitted to do so without state certification or oversight. This is despite confirmation of more than a dozen cases of herpes transmission, two cases of permanent brain damage, and two infant deaths likely caused by the practice between 2004 and 2012.

Those are just the figures for New York City. But still there are no legal restrictions. As the bioethicist Dena Davis has pointed out, “states currently regulate the hygienic practices of those who cut our hair and our fingernails, so why not a baby’s genitals?”

She means “baby boy’s” genitals; baby girls’ genitals are protected by law.

The Bohra defense team will likely flag these inconsistencies. If ritual male circumcision is not only legally permitted but completely unregulated in the US, they will argue, then how can a procedure that carries fewer risks and is less physically damaging be classified as a federal crime? They will also point to the religious significance of “female circumcision” among the Bohra. They will ask: aren’t religious practices granted strong legal protections in the United States and other Western countries?

The prosecution will almost certainly make two moves in response. First, they will argue that FGM is not truly a religious practice, but is “merely” a cultural tradition, because there is no mention of female circumcision in the Koran. And second, they will point out that male circumcision has been linked to certain health benefits, whereas FGM “has no health benefits” (as stated by the WHO).

But things are not so simple. It is true that female circumcision is not mentioned in the Koran; but neither is male circumcision. And yet the latter is widely regarded as a “religious” practice not only within Judaism but also Islam. As Alex Myers notes, “if we defer to religious justifications, we shall find that in many cases, the circumcision of female as well as male children could be permitted on this basis.”

How could that be so? In her landmark paper entitled, “Male and Female Genital Alteration: A Collision Course with the Law,” Dena Davis notes that “binding religious obligations” can stem from oral traditions and other “extrabiblical sources,” such as rabbinic commentaries or papal encyclicals in the case of Judaism or Christianity. Likewise, “Islam looks to other sources to interpret and supplement Koranic teachings.”

One such source is the Hadith—the sayings of the Prophet Mohammed—which is the other major basis for Islamic law apart from the Koran.

Both male and female circumcision are mentioned in the Hadith. Based on their reading of the relevant passages, some Muslim authorities state that “circumcision” of both sexes is recommended or even obligatory, while others draw a different conclusion. There is no ultimate authority in Islam to settle such disputes, however, so debate continues to this day.

What this means is that, until a consensus is reached in the Muslim world, the status of female genital cutting as a “religious” or “cultural” practice will depend on each community’s local evaluation of secondary Islamic scriptures. Dawoodi Bohra clerics view the practice as religious.

This leads to an uncomfortable thought. In the West, we seem more or less unfazed by the religiously sanctioned cutting of boys’ genitals; but we go into a panic over less severe procedures performed on the genitals of girls by equally pious parents.

In fact, we bend over backwards to convince ourselves that the latter procedures are “not actually religious” by selectively citing scholars who agree with us—as though not being “religious” somehow made a practice less worthy of being respected, or being “religious” made it morally OK. Neither of those propositions follow.

Finally, we attribute evil motives to the parents who circumcise their daughters, when the same parents almost invariably also circumcise their sons, sometimes more invasively, and often for identical reasons. (The stereotype that female circumcision is “all about” misogyny and sexual control, while male circumcision is about neither, is one that I, and many other scholars, have deconstructed elsewhere: see here for a fairly short summary. Suffice it to say the claim is not true.)

So who are we kidding? The overwhelming majority of American parents who circumcise their sons do it for “cultural” rather than religious reasons, and few seem concerned to bat an eye. Many Jews who circumcise are committed atheists (and, for all I know, so are many Muslims). Although the law may treat “religion” as a special, separate category, the religious versus “cultural” status of male or female genital cutting is not what drives our different moral judgments.

So maybe it’s “health benefits.” Maybe we think male circumcision is acceptable because it has medical advantages, whereas female circumcision only has “social” advantages (eligibility for marriage, greater acceptance by the community, seen as more aesthetic, and so on).

I don’t think that’s the solution, either. First, the idea that “social” benefits are less important than “health” benefits would need some defending: I have already mentioned the pitfalls of capitulating to the domain of medicine in order to avoid having to think through complex moral issues. But let us just assume that all we care about is “health” for a moment and see where this exercise leads us.

Most of the decent-quality data showing health benefits for male circumcision (primarily, a modest reduction in the absolute risk of some sexually transmitted infections) come from surgeries performed on adults in Africa, not babies in the United States or Europe. The findings cannot be simply copy-pasted from one context and age range to another.

But even if you could just copy and paste, you would still have to factor in the risks and harms of circumcision, which are not trivial. In fact, most national medical associations to have issued formal policies on the question have found that the benefits of childhood male circumcision are not sufficient to outweigh the disadvantages of the surgery in developed countries.

(There is one glaring exception to this, which we’ll come back to.)

This suggests either that the scales are closely balanced, as the Canadian Pediatric Society claims, or actually tipped in the direction of net harm, as the Royal Dutch Medical Association has concluded. Further south, the Royal Australasian College of Physicians states: “the level of protection offered by circumcision and the complication rates of circumcision do not warrant routine infant circumcision in Australia and New Zealand.”

In any case, the existence of “some” health benefits (as opposed to net health benefits—and that would still not resolve the moral issues) would make for a very weak defense of the practice even on purely medical grounds.

Just think. Removing any healthy tissue from a child’s body will confer “some” health benefits: tissue that has been excised can no longer host a cancer, become infected, or pose any other problem to its erstwhile owner. But as the bioethicist Eike-Henner Kluge has noted, if this logic were accepted more generally, “all sorts of medical conditions would be implicated” and we would find ourselves “operating non-stop on just about every part of the human body.”

Alarmingly, one place we might start operating is the pediatric vulva. Compared to the penis, the external female genitalia provide if anything “an even more hospitable environment to bacteria, yeasts, viruses, and so forth, such that removing moist folds of tissue (with a sterile surgical instrument) might very well reduce the risk of associated problems.”

In countries where female circumcision is relatively common, this is exactly what is claimed for the procedure. Cited health benefits include “a lower risk of vaginal cancer … fewer infections from microbes gathering under the hood of the clitoris, and protection against herpes and genital ulcers.”

Moreover, at least two studies by Western scientists have shown a negative correlation between female circumcision and HIV. The authors of one of the studies, both seasoned statisticians who expected to find the opposite relationship, described their findings as a “significant and perplexing inverse association between reported female circumcision and HIV seropositivity.”

None of these findings is conclusive. I am not saying that female “circumcision” can ward off HIV or any other disease. But let us just imagine that some of the above-cited health benefits are eventually confirmed. Would anti-FGM campaigners suddenly be prepared to say that female genital cutting was ethically acceptable?

I would be surprised if that turned out to be the case. In other words, even if health benefits do one day become reliably associated with some medicalized form of female genital cutting, I expect that opponents of the practice—including the WHO—would say, “So what?”

First, they would argue that healthy tissue is valuable in-and-of-itself, so should be counted in the “harm” column simply by virtue of being damaged or removed. Second, they would point to non-surgical means of preventing or treating infections, and suggest that these should be favored over more invasive methods. And third, they would bring up the language of rights: a girl has a right to grow up with her genitals intact, they would say, and decide for herself at an age of understanding whether she would like to have parts of them cut into or cut off.

The same arguments apply to male circumcision. But as Kirsten Bell has pointed out, the WHO steadfastly refuses to connect the dots. In her words, they seek to “medicalize male circumcision on the one hand” by promoting it, over the objections and reservations of many outside experts, as a form of prophylaxis against HIV. But they “oppose the medicalization of female circumcision on the other, while simultaneously basing their opposition to female operations on grounds that could legitimately be used to condemn the male operations.”

The problem with appeals to “health benefits,” then, is that they are disingenuous and inconsistently applied. As Robert Darby has argued, “official bodies working against FGC have condemned medicalization of the procedure and funded massive research programs into the harm of the surgery.” The irony, as he sees it, is that the WHO “also frames male circumcision as a public health issue—but from the opposite starting point.” Thus, we see that

instead of a research program to study the possible harms of circumcision, it funds research into the benefits and advantages of the operation. In neither case, however, is the research open-ended: in relation to women the search is for damage, in relation to men it is for benefit; and since the initial assumptions influence the outcomes, these results are duly found.

Perhaps even more striking, the WHO’s asymmetrical focus on health benefits could backfire. Specifically, it could open the door for supporters of female genital cutting to mount a defense of the procedure modeled on the male parallel.

To put it simply, if the sheer existence of health benefits is so compelling to organizations like WHO, these supporters might think, then all we have to do is generate the right kind of evidence, and we can fend off critics of our cherished custom.

There are already signs of this happening. At least one female Muslim gynecologist—from Khartoum University in the Sudan—has been reported as saying: “if the benefits [of female circumcision] are not apparent now, they will become known in the future, as has happened with regard to male circumcision.”

(Perhaps she will be inspired by the websites of American plastic surgeons, who already claim all manner of physical and mental health benefits for elective labiaplasty – and other purported “cosmetic” operations).

Similarly, the anthropologist Fuambai Ahmadu has written about the women of Sierra Leone: “Why, one woman asked, would any reasonable mother want to burden her daughter with excess clitoral and labial tissue that is unhygienic, unsightly and interferes with sexual penetration … especially if the same mother would choose circumcision to ensure healthy and aesthetically appealing genitalia for her son?”

And what about the Dawoodi Bohra? As reported by Tasneem Raja, herself a member of the community and a former editor at NPR, some Bohra women believe that female circumcision, which they call khatna, “has something to do with ‘removing bad germs’ and liken it to male circumcision, which is widely … believed to have hygienic benefits.”

It is currently illegal in Western countries to conduct a properly controlled scientific study to determine whether a “mild,” sterilized form of female genital cutting carried out in infancy or early childhood confers some degree of protection against disease.

But if anti-FGM campaigners and organizations such as the WHO continue to play the “no health benefits” card as a way of deflecting comparisons to male circumcision, it will not be long before medically-trained supporters of the practice in other countries begin to do the necessary research.

The history of male circumcision shows how this could happen. Alongside female genital cutting, male genital cutting originated in African prehistory as a ritual practice, and was later adopted by various Semitic tribes. For most of its existence, the only claimed advantages of the procedure were social or metaphysical in nature—identifying the boy as a member of a particular group, for example, or sealing a divine covenant, as in Judaism.

In the physical realm, by contrast, circumcision was largely believed to have negative effects, including on sexual feeling and satisfaction. By “dulling” the sexual organ of male children, parents believed that their sons would pay more attention to important “spiritual” matters and be less tempted by the pleasures of the flesh.

It was only in recent times that religious supporters of male circumcision began to argue that it was “physically” beneficial—recasting the procedure as a secularly defensible measure of individual or even public health, as opposed to solely a cultural or religious practice.

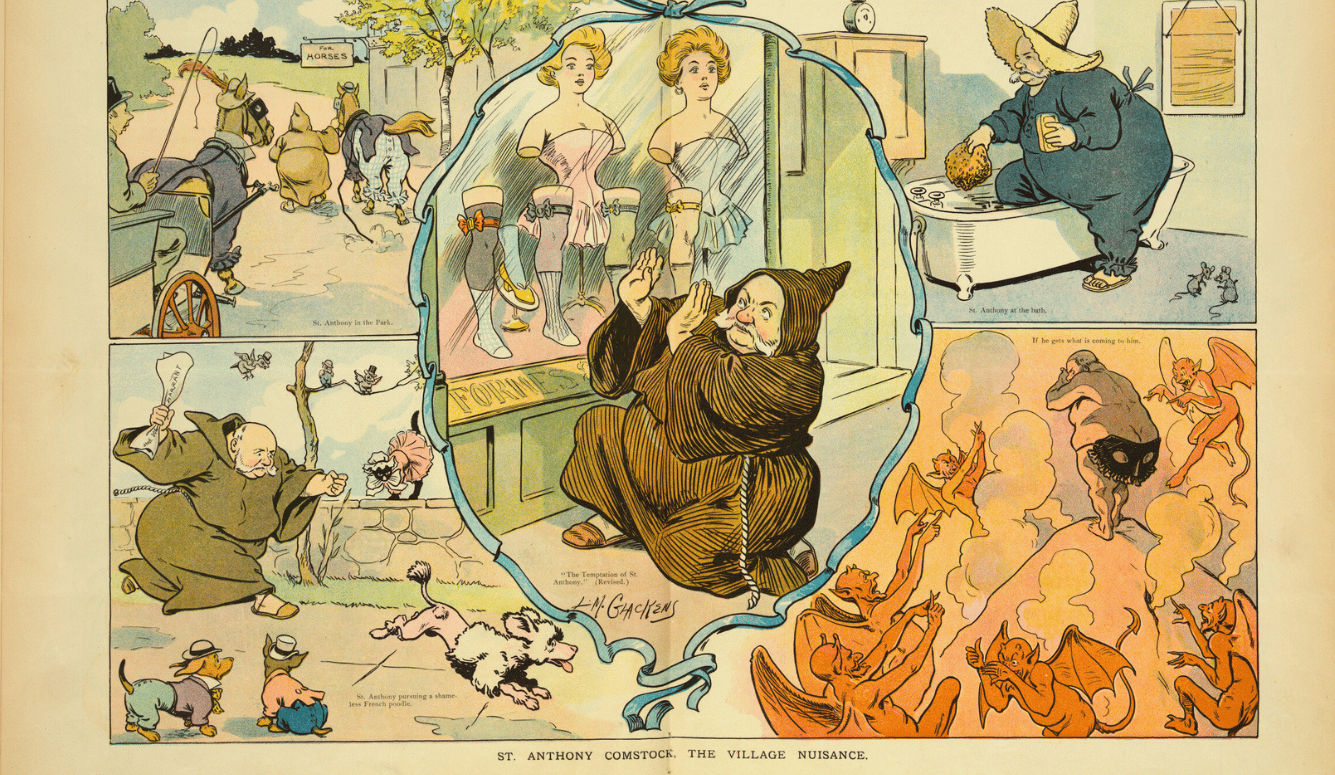

In the United States, for example, circumcision was adopted in part as an anti-masturbation tactic in the late 1800s (masturbation, at the time, was thought to cause not only moral but medical ills; see here for a video introduction). The resulting shift from “religious” to “medical” proved strategically important in Christian-majority societies, where genital cutting of children had otherwise been seen as barbaric.

The medical historian David Gollaher has argued that Jewish physicians, whose “attitudes toward circumcision were partly shaped by their own cultural experience,” found the late 19th century evidence of health benefits “especially compelling.” Most of it was later debunked.

Nevertheless, the search for “health benefits” continues to this day. A large proportion of the current medical literature purporting to show health benefits for male circumcision has been generated by doctors who were themselves circumcised at birth—often for religious reasons—and who have cultural, financial, or other interests in seeing the practice preserved.

Science and medicine are not immune from such agendas or biases. In 2012, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) controversially concluded that the health benefits of newborn male circumcision outweighed the risks (this is the “glaring exception” I said I’d come back to). Their conclusion was puzzling, since they did not have a method for assigning weights to individual benefits or risks, much less an accepted mechanism by which the two could be compared.

They were also missing the denominator to their equation. On page 772 of their report they state that, due to limitations with the existing data, “the true incidence of complications after newborn circumcision is unknown.”

So how could we know they are outweighed by the benefits?

In an unprecedented move, the AAP was rebuked by senior physicians, ethicists, and representatives from national medical societies based in the UK, Canada, and mainland Europe, who argued that the findings were likely culturally biased. The AAP Circumcision Task Force later acknowledged that the benefits were only “felt” to outweigh the risks. It came down to a subjective judgment.

Reflecting on the debacle in a recent editorial, Task Force member Andrew Freedman tried to explain how he and his colleagues had reached a different conclusion to that of their peers in other countries despite looking at the same medical evidence. In doing so, he made a revealing comment:

Most circumcisions are done due to religious and cultural tradition. In the West, although parents may use the conflicting medical literature to buttress their own beliefs and desires, for the most part parents choose what they want for a wide variety of nonmedical reasons. There can be no doubt that religion, culture, aesthetic preference, familial identity, and personal experience all factor into their decision.

In a separate interview, Freedman stated that he had circumcised his own son on his parents’ kitchen table. “But I did it for religious, not medical reasons,” he wrote. “I did it because I had 3,000 years of ancestors looking over my shoulder.”

Arguing that it is “not illegitimate” for parents to consider such social and spiritual “realms [in] making this nontherapeutic, only partially medical decision,” Freedman went on to say that “protecting” the parental option to circumcise “was not an idle concern” in the minds of the AAP Task Force members “at a time when there are serious efforts in both the United States and Europe to ban the procedure outright.”

The women in societies that practice what they call female circumcision are just as devoted to their cultural traditions as are the men who practice genital cutting of boys. They don’t want their customs banned either. If “medical benefits” are sufficient to ward off condemnation, a strong incentive will exist to seek them out.

I suggest, therefore, that by repeating the mantra—in nearly every article focused on female genital cutting—that “FGM has no health benefits,” those who oppose such cutting are sending the wrong signal. The mantra implies that if FGM did have health benefits, it wouldn’t be so bad after all.

But that isn’t what opponents really think. Regardless of health consequences, they see nontherapeutic genital cutting of female minors as contrary to their best interests, propped up by questionable social norms that should themselves be challenged and changed.

I would go one step further. All children—female, male, and intersex—have a compelling interest in intact genitalia. All else being equal, they should get to decide whether they want their “private parts” nicked, pricked, labiaplastied, “normalized,” circumcised, or sewn, at an age when they can appreciate what is really at stake.

This doesn’t mean a “ban” on such procedures before an age of consent is necessarily the best way to go. As I have explained elsewhere, legal prohibition can be a clumsy way of bringing about social change, often causing more harm than good. I worry, for example, that that taking young girls out of their homes, invasively examining their genitals in search of “evidence,” and throwing their parents—who no doubt love them—in jail, could be more traumatic than the initial act of cutting.

As for the Dawoodi Bohra case, we will just have to see how the judge interprets—and applies—the existing laws.

My own preference is for debate and dialogue, not bans and vilification. But whatever approach one takes, it is time to move beyond the tired (and false) dichotomies of male versus female, religion versus culture, and health benefits versus no health benefits. The focus for critics of genital cutting going forward, I contend, should be on children versus adults—that is, on bodily autonomy and informed consent.

Key references

Abdulcadir, J., Ahmadu, F. S., Catania, L., & Public Policy Advisory Network on Female Genital Surgeries in Africa (2012). Seven things to know about female genital surgeries in Africa. The Hastings Center Report, 42(6), 19-27.

Bell, K. (2015). HIV prevention: making male circumcision the ‘right’ tool for the job. Global Public Health, 10(5-6), 552-572.

Bell, K. (2005). Genital cutting and Western discourses on sexuality. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 19(2), 125-148.

Darby, R. (2015). Risks, benefits, complications and harms: neglected factors in the current debate on non-therapeutic circumcision. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal, 25(1), 1-34.

Darby, R. (2016). Targeting patients who cannot object? Re-examining the case for non-therapeutic infant circumcision. SAGE Open, 6(2), 1-16.

Darby, R., & Svoboda, J. S. (2007). A rose by any other name? Rethinking the similarities and differences between male and female genital cutting. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 21(3), 301-323.

Davis, D. S. (2001). Male and female genital alteration: a collision course with the law? Health Matrix, 11(1), 487-570

Dustin, M. (2010). Female genital mutilation/cutting in the UK: challenging the inconsistencies. European Journal of Women’s Studies, 17(1), 7-23.

Ehrenreich, N. (2005). Intersex surgery, female genital cutting, and the selective condemnation of cultural practices. Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review, 40(1), 71-539.

Fox, M., & Thomson, M. (2009). Foreskin is a feminist issue. Australian Feminist Studies, 24(60), 195-210.

Frisch, M., Aigrain, Y., Barauskas, V., Bjarnason, R., Boddy, S. A., Czauderna, P., … & Gahr, M. (2013). Cultural bias in the AAP’s 2012 Technical Report and Policy Statement on male circumcision. Pediatrics, 131(4), 796-800.

Giami, A., Perrey, C., de Oliveira Mendonça, A. L., & de Camargo, K. R. (2015). Hybrid forum or network? The social and political construction of an international ‘technical consultation’ on male circumcision and HIV prevention. Global Public Health, 10(5-6), 589-606.

Gollaher, D. L. (1994). From ritual to science: the medical transformation of circumcision in America. Journal of Social History, 28(1), 5-36.

Goodman, J. (1999). Jewish circumcision: an alternative perspective. BJU international, 83(S1), 22-27.

Gruenbaum, E. (1996). The cultural debate over female circumcision: the Sudanese are arguing this one out for themselves. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 10(4), 455-475.

Hammond, T., & Carmack, A. (2017). Long-term adverse outcomes from neonatal circumcision reported in a survey of 1,008 men: an overview of health and human rights implications. The International Journal of Human Rights, 21(2), 189-218.

Hodges, F. (1997). A short history of the institutionalization of involuntary sexual mutilation in the United States. In Sexual Mutilations (pp. 17-40). New York: Springer US.

Hodžić, S. (2013). Ascertaining deadly harms: aesthetics and politics of global evidence. Cultural Anthropology, 28(1), 86-109.

Johnsdotter, S., & Essén, B. (2010). Genitals and ethnicity: the politics of genital modifications. Reproductive Health Matters, 18(35), 29-37.

Johnson, M. (2010). Male genital mutilation: beyond the tolerable? Ethnicities, 10(2), 181-207.

Lightfoot-Klein, H., Chase, C., Hammond, T., & Goldman, R. (2000). Genital surgery on children below the age of consent. In Psychological Perspectives on Human Sexuality (pp. 440–79). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Mason, C. (2001). Exorcising excision: medico-legal issues arising from male and female genital surgery in Australia. Journal of Law and Medicine, 9(1), 58-67.

Obiora, L. A. (1996). Bridges and barricades: rethinking polemics and intransigence in the campaign against female circumcision. Case Western Reserve Law Review, 47, 275.

Reis-Dennis, S., & Reis, E. (2017). Are physicians blameworthy for iatrogenic harm resulting from unnecessary genital surgeries? AMA Journal of Ethics, 19(8), 825-833.

Shahvisi, A. (2017). Why UK doctors should be troubled by female genital mutilation legislation. Clinical Ethics, 12(2), 102-108.

Shell‐Duncan, B. (2008). From health to human rights: female genital cutting and the politics of intervention. American Anthropologist, 110(2), 225-236.

Shweder, R. A. (2013). The goose and the gander: the genital wars. Global Discourse, 3(2), 348-366.

Shweder, R. A. (2000). What about “female genital mutilation”? And why understanding culture matters in the first place. Daedalus, 129(4), 209-232

Solomon, L. M., & Noll, R. C. (2007). Male versus female genital alteration: differences in legal, medical, and socioethical responses. Gender medicine, 4(2), 89-96.

Steinfeld, R., & Earp, B. D. (2017). How different are male, female, and intersex genital cutting? The Conversation. May 15.

Svoboda, J. S. (2013). Promoting genital autonomy by exploring commonalities between male, female, intersex, and cosmetic female genital cutting. Global Discourse, 3(2), 237-255.

Van den Brink, M., & Tigchelaar, J. (2012). Shaping genitals, shaping perceptions: a frame analysis of male and female circumcision. Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights, 30(4), 417-445.

Van Howe, R. S. (2011). The American Academy of Pediatrics and female genital cutting: when national organizations are guided by personal agendas. Ethics and Medicine, 27(3), 165-173.

Further related reading by the author (by year)

Earp, B. D., Hendry, J., & Thomson, M. (2017). Reason and paradox in medical and family law: shaping children’s bodies. Medical Law Review, in press.

Earp, B. D. & Shaw, D. M. (2017). Cultural bias in American medicine: the case of infant male circumcision. Journal of Pediatric Ethics, in press.

Earp, B. D., & Frisch, M. (2017). Circumcision of male infants and children as a public health measure in developed countries: a critical assessment of recent evidence. Global Public Health, in press.

Earp, B. D., & Darby, R. (2017). Circumcision, sexual experience, and harm. University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Law, 37(2), 1-56.

Earp, B. D., & Steinfeld, R. (2017). Gender and genital cutting: a new paradigm. In T. G. Barbat (Ed.), Gifted Women, Fragile Men. Euromind Monographs – 2, Brussels: ALDE Group-EU Parliament.

Earp, B. D. (2016). Between moral relativism and moral hypocrisy: reframing the debate on “FGM.” Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal, 26(2), 105-144.

Earp, B. D. (2016). In defence of genital autonomy for children. Journal of Medical Ethics, 42(3), 158-163.

Earp, B. D. (2016). Boys and girls alike: the ethics of male and female circumcision. In E. C. H. Gathman (Ed.), Women, Health, & Healthcare: Readings on Social, Structural, & Systemic Issues (pp. 113-116). Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt Publishing Company.

Earp, B. D. (2016). Infant circumcision and adult penile sensitivity: implications for sexual experience. Trends in Urology & Men’s Health, 7(4), 17-21.

Earp, B. D. (2015). Female genital mutilation and male circumcision: toward an autonomy-based ethical framework. Medicolegal and Bioethics, 5(1), 89-104.

Earp, B. D. (2015). Sex and circumcision. The American Journal of Bioethics, 15(2), 43-45.

Earp, B. D. (2015). Do the benefits of male circumcision outweigh the risks? A critique of the proposed CDC guidelines. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 3(18), 1-6.

Earp, B. D., & Darby, R. (2015). Does science support infant circumcision? The Skeptic, 25(3), 23-30.

Earp, B. D. (2014). Female genital mutilation (FGM) and male circumcision: Should there be a separate ethical discourse? Practical Ethics. University of Oxford.

Earp, B. D. (2013). The ethics of infant male circumcision. Journal of Medical Ethics, 39(7), 418-420.

Earp, B. D. (2013). Criticizing religious practices. The Philosophers’ Magazine, 63(1), 15-17.

Earp, B. D. (2012). The AAP report on circumcision: bad science + bad ethics = bad medicine. Practical Ethics. University of Oxford.