Memoir

“Have You Found the Place that Makes You Want to Swallow Its Rhetoric Whole?”

Sadie insisted, apropos of nothing, that she was “really a radical feminist.”

The line above is drawn from a Facebook post entitled “To Any Folks Who Ever Want to Date Me: an anthem for 2017 singles.” Written by an apparently earnest young leftist activist feminist, the anthem begins with a list of verboten statements and actions that a prospective (non-social-justice-activist) mate may err in saying or doing. It then moves onto the preferable approaches that appropriate types might undertake, inclusive of the line that is the title of this piece:

Do not dare to comment on my body. Do not stare. Do not tell me all the things you want to do to me. Do not force me to bear the weight of your assumptions. Do not waste both of our time with things so hollow as this. Do not make wishes on my freckles. Do not touch my waist. Do not tell me I am precious, or pretty. Do not seek to make me smaller. Do not ask me to fit.

Instead, tell me a story. Tell me a secret. Tell me where you come from. Are you a communist? A socialist? Where is your activist home? Have you found the place that makes you want to swallow its rhetoric whole?

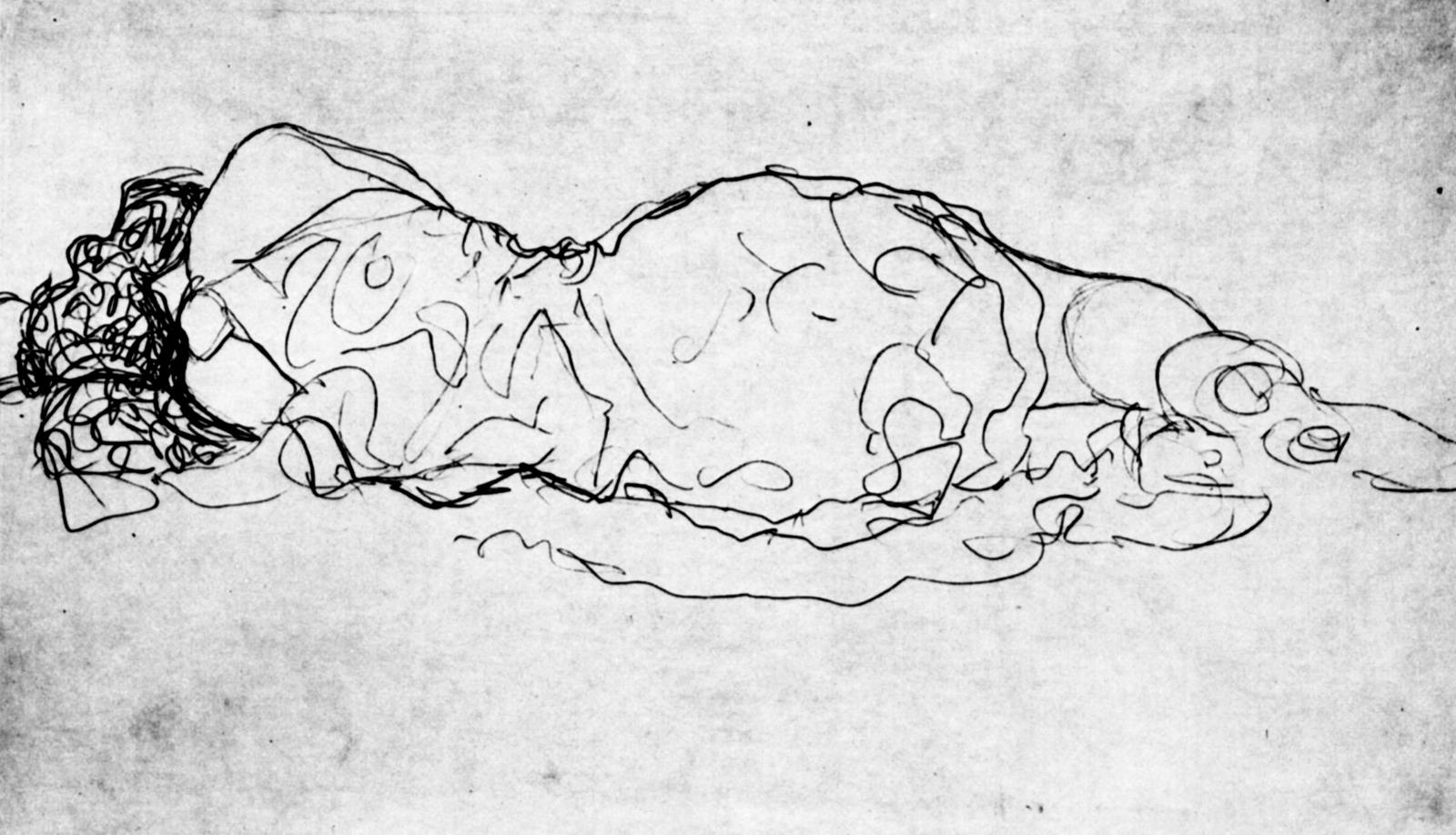

The question is so redolent – or dare I say pregnant – with hermeneutic possibilities that one hardly knows where to begin. But let’s start with the obvious: the sublimation of sex. Having foreclosed remarks about the body no matter how flattering, having shut down the “male gaze,” eliminating the possibility for feckless romanticism (including wishing upon freckles), anathematizing the touch however slight, and turning compliments into crimes, the young would-be lover lies well beyond the grasp of the standard-issue aspirant.

Only a particular type will do, only a particular type will know that only language and a particular kind of language will open the lock: a story, a secret, but preferably a confession of having swallowed whole the rhetoric of a particular leftist political tribe. This is the only way in – but to what? The seeker can gain admission to an apparent blind alley only by pledging sexual renunciation at the outset, as well as, as a replacement for sexuality, the wholesale inculcation of some socialist-communist creed, no doubt the more obscure and hopeless the better. One cannot but imagine sputum (or something) dripping from this obsequious supplicant’s lips, while he, she, ze, they, or whatever, confesses fealty to a leftist doctrine and begs admission to the cult of the goddess. Sex has been fully sublimated into religio-political devotion.

Now, to turn to the other disturbing aspects of this passage: its further implications regarding the contemporary Left. First, I wish to express my gratitude for its having been enunciated. It so clearly epitomizes the demand for uncritical acceptance of an ideology, especially given the use of the word “rhetoric” – the received connotation for which is added flourishes extraneous to content or substance and the denotation for which is the language of persuasion or propaganda – that one could not have asked for a better expression.

This is why the question has become a sort of reverse meme bandied about among my friends and me on social media. And, for some time, I have been arguing against just this kind of uncritical and anti-intellectual acceptance of received notions, especially in connection with the academic, “social justice” Left, which relies on knee-jerk responses to supposed infringements of its values and identities. This is the poll parrot, phrase-repeating, slogan-mongering Left that chants mindlessly to no-platform speech the illiberal leftists deem intolerable. It is the Left of the successful Stanford admissions essay that repeats “Black Lives Matter” a hundred times. The Left that swallows its own rhetoric whole.

This is the Left that I inadvertently introduced to my ex-partner some eight or nine years ago, and which eventually became one of the primary obstacles to an ongoing relationship. She may not see it that way, but I do. What follows is a somewhat agonizing tale for me to narrate, yet one necessary to expel. I cannot chronicle the entire relationship with the astonishing Sadie, but some of the history is necessary for showing how the swallowing whole of a political rhetoric became the final obtrusion that ended what had been an extraordinary love.

We met under rather inconsequential circumstances in the spring of 2003. From the moment that I laid eyes on her, I knew without a doubt that she was destined to be mine. I had no trepidation about this prospect. It lay like an eventuality about to unfurl before me, between us. I only had to participate and follow the somewhat obscure but nevertheless preordained narrative. While this may sound romantic to the point of delusion – and allow me to say that I am an otherwise cynical person – I firmly believed and still do that the truth of our love existed well before our meeting. It was just there, waiting for us to discover it.

The group we were part of sat in a circle and we sat across from each other, she in cut-off jeans. For reasons that I do not fully understand, her knobby knees, and affected, humble-bragging confessions of artistic doubt were sure signs of this inevitability. I think now that the latter indicated vulnerability and the former a peculiar beauty that needed no apology or adornment. Somehow, both were clear signs of our fateful connection.

At the time, however, I was married, a father of three, in a marriage with my wife Heather that had been troubled for several years. I had been working as a writer in an Artificial Intelligence lab of the Robotics Institute at Carnegie Mellon University, and was also a Ph.D. candidate in the English department at the same university. I was writing a dissertation on nineteenth-century British science cultures. I would wake at six, be at my office by seven, and work on the dissertation until the programmers arrived in the early afternoon. If the project manager had any work for me, I would put the dissertation on hold and switch to writing about the AI software under development.

As it happened, I was left alone to work on the dissertation uninterrupted – often for hours, days, and weeks on end. I finished the dissertation in two years. In a field in which the average total start-to-finish time for the Ph.D. is eight years, I was done in just over seven, submitting an oversized, 420-plus page dissertation seven years and one month after beginning program. During my time in the Ph.D. program and the three years in an M.A. program before that, I had also worked full-time, often more than full-time, on top of the full-time classwork, and the reading, teaching, and writing.

Meanwhile, coming as it did in my early thirties, this change in careers (from advertising executive to budding academic) put considerable stress on the marriage. Not only did the time spent taking classes, then studying for exams, then writing the dissertation, eat into our time together, but also and especially my obsession with the field proved to be driving us apart. Little did I know that this situation would be paralleled by another, similar one in the future. Heather worked in real estate and my rather arcane pursuits were quite remote from her interests. She wanted to continue the marital and family life that we had had hitherto engaged in somewhat normally (although even earlier it had been troubled by other factors), but which seemed to be slipping away from her and seemed to me more absurd as I delved further into my pursuits. By the time I met Sadie, I had been convinced for at least three years that the marriage was loveless and effectively over.

Sadie was a renowned, New York choreographer on a paid visiting artist-in-residence gig at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. Over our first dinner together, she expressed a sophisticated interest in my field of study and even knew about some of its leading lights. I remember distinctly as she said, cultural studies, enunciating the phrase laughingly but also with a peculiar emphasis indicative of knowing what she was talking about, then mentioning Foucault and other theorists with familiarity.

She was clearly impressed. As was I. There was something very immediate about the attraction but it pointed to something beyond the mere signaling. A confluence of interests and something else, a sense of profound familiarity, were clear to us both. Mostly importantly, perhaps, she was the only woman I had ever met who had bitten her fingernails to the point of disfigurement, much as I had mine. Her targets were thumbs, while mine were baby fingers. As we both saw it, this was the ultimate sign to seal our union. When, that first night after dinner, she said, “goodbye Michael,” I knew it would not be the last time that I would hear those words from her lips. Her careful naming of me was a kind of love-making; she formed my name in her mouth and issued it forth with care, as if delivering me to me.

When we drove in my van to a bar in Monroeville to hear a friend’s band play, she complained about the suburbs like an adolescent. And I chided her lightly for the immaturity. After that night, I lost track of her. Her six-week artist-in-residence stint neared its end and her return to New York was imminent. For some reason, I made no plans with her, nor did I ask for her email address or phone number.

On the Sunday when I knew she due to leave, I drove to Shadyside, the neighborhood where she’d stayed. I was desperate to make it to the door before she’d disappeared. Racing in the van from Point Breeze, I heard a flapping, thumping sound. I changed the tire in the middle of Fifth Avenue. But by the time the spare was on, it was late afternoon and my hands were covered in grease. I rushed to the door of the house. The romanticism of the situation was not lost on me. I played a part in a movie and this was one of the most gripping scenes. I knocked. I rang the bell. I repeated, again and again. But no one answered. Sadie was gone.

The next morning, I sat in my office, desperate. Had I really let her slip away?

By 9 AM, I received an email – from her: a chipper and fetching communique. It was on. We were on. My belief was vindicated. From that point, the communication between us was never to be risked again by indolence on my part, or by impudence on hers. It was constant, intense and extremely exciting. It brought her back to Pittsburgh for visits in no time, and took me to New York as well.

There are many salient episodes in the romance that I could add – like when we were spiritually “married” during an Easter Sunday service at Grace Episcopal church on Broadway in Noho and we felt the kneading together of our souls. Or the time we went to a dance performance in Union Square that took place above us on ropes and we peered into the air together, then kissed. Or the time we took a bus from Soho to Tribeca and she lightly laid her head on my shoulder, trusting.

Eventually, I knew I had to break it to Heather. One Sunday night, I left the house for my office, something I often did to get some relief from our marital strife. Once in the office, I called Sadie. I sat with my office door open, talking to Sadie freely for over an hour. Little did I know, Heather had followed, snuck into the office building behind me, and had been listening outside my office door. After I hung up, Heather walked into my office and my heart jumped. Her presence struck me as incongruous, wrongly placed, utterly. She was a very significant figure. She confronted me directly. What was this about? Stunned, I confessed everything. Within mere weeks, Heather and I sold a rental property in Shadyside and I bought another house a few blocks from our family home. I moved by May and I managed to convince Sadie to leave her beloved New York to live with me soon after. She arrived before Mother’s Day.

I know that Sadie moved in before Mother’s Day because on Mother’s Day, Heather came to the house to confront us, but especially Sadie. I locked the doors and refused to answer. Sadie hid in the basement, terrified as Heather pounded on the front door first, rang the bell repeatedly, then moved to the back door and pounded on it, yelling in. I completely ignored her. That was her Mother’s Day gift from me, I suppose, and I still regret that the day transpired as it did.

After nearly a year in Pittsburgh, Sadie decided to begin a year-long, low-residency M.F.A. in dance. In hindsight, I suppose she had visions of becoming an academic, like me. She left for Hollins University in Virginia and left me alone in Pittsburgh.

Then, amazingly, I got an academic job in Durham, NC. This was truly incredible because Sadie had to finish the remainder of her M.F.A. at the American Dance Festival, which was held at Duke University in Durham in the fall. So, we were back together in a spacious loft adjacent to Duke’s East Campus. Sadie told me later of having had a dream, while still living in New York, wherein we walked together through an idyllic college campus, apparently in our new world together. The fortuitous confluence of our lives continued.

If this were not enough, after two years in Durham, Sadie went on the academic job market and asked me to look for a job in New York as well. She wanted to get back to her career as a choreographer in the downtown avant-garde scene. We both applied for jobs in and around New York. I landed a job at NYU and she a position at Gettysburg College, just over three hours from New York. We both accepted our offers and thus began my town and country life, living in Sadie’s rent-stabilized apartment on Mott Street in New York during the week, and commuting to South Central Pennsylvania on weekends, while living with her over breaks and summers. Thus, we had realized our dream of being mostly together, having academic jobs, and I relished both the city and the province – and whatever time I could squeeze from Sadie’s now extremely demanding schedule.

It didn’t take long for me to begin resenting Sadie’s job – not only that she was making more money than me, that she was the director of a dance program, that she was on tenure-track while I was on a long-term renewable contract, but also and mostly because her job became her new lover. I found myself travelling three plus hours every Friday, only to sit and wait for her to finish some school activity – a rehearsal; a show; a meeting with students, parents or prospective students; or, all of the above.

As for the envy, I had completed ten years of graduate study culminating in the M.A. and Ph.D., while she had undertaken a year-long, low-residency M.F.A. program. Yet she landed the tenure-track and I the contract job. This disparity of preparations and outcomes definitely grated on me. Further, her college was lodged on a pastoral, idyllic campus, like the one she had dreamed about, while I had to negotiate security checks upon entering every over-crowded building on NYU’s “campus.” To top it off, Sadie had received a sizeable loan from her father, and managed to buy a house only a few hundred yards from her office building. By contrast, having to move from her apartment after a landlord dispute, I began the desperate struggle to secure decent housing in New York.

But aside from her obviously better situation, the real rub was the time she spent on the job, which amounted to no less than eighty hours a week. As she reminded me time and again, hers was a residential campus; the students expected faculty involvement, not only during classes but also in numerous extracurricular activities, almost around the clock. I saw this solicitousness as disgusting handholding and insipid over-nurturance, and for Sadie, surrogate parenting. Being on tenure track, she was extremely conscientious about doing everything asked of her. She never said no. And as a member of a theatre and dance program, notoriously time-intensive fields, the opportunities for activities were endless. And to compound matters, Sadie’s insecurities about teaching made her obsessive-compulsive in her preparations for classes. Likewise, despite her somewhat feeble attempts to integrate me into her life, I was increasingly left out.

I recalled a recurring childhood dream: I am a small boy standing outside of a large supermarket on a fall afternoon. Hundreds of people bustle past in all directions, pushing shopping carts. I try to cry out to them, but they can’t hear or else ignore me. And every one is my mother. I realized that our relationship was failing us both, but for precisely the opposite reasons. Sadie saw me as the menacing male trying to derail her career as her father had supposedly short-thrifted her “That Girl” ambitions in favor of her brothers. I saw her as a replica of my mother, never having time for me.

Sadie insisted, apropos of nothing, that she was “really a radical feminist.” I scoffed at this suggestion, saying that she merely thought she should be a radical feminist and that she wasn’t really a radical feminist at all. So as if to prove herself a radical feminist, she went on to rant about “dick culture,” “white male dickheads,” and, during the political talk shows, “talking dickheads.” It all seemed juvenile to me, much like her scorning of the suburbs had been. Sometimes, she would suddenly demand to know why I was looking at her face. You’re talking, I would answer. That’s where the words seem to be coming from. She insisted that I was inspecting her. I tried to explain that if I was lingering on her features for a half-second beyond the time permissible, I did so because I found her face exquisitely beautiful. But that was never satisfactory.

I decided to teach a year abroad at NYU’s campus in London, feeling less than obligated to gain Sadie’s approval, although I did ask and she did grant it. It seemed as if she might even have been happy to get rid of me. I was a chore. But I ignored this in light of the prospects. I would have free, luxurious housing with great amenities, and a light teaching schedule with no service work to speak of. Thus, I would find the time and wherewithal to undertake archival research for a project I’d been delaying work on for several years, and this work helped me turn the corner on the publication front. But I was lonely as hell.

I have not yet mentioned that I had sworn off drinking over fifteen years earlier, but after returning from England I began to occupy my time with the help of another substance: Adderall. Sadie and I would work, she upstairs and I downstairs, twelve to fifteen hours a day, with almost no interaction between us. I used to joke that the secret of our success was that we agreed to ignore each other.

The good news was that as I joined Sadie in her careerist obsession, I grew much less concerned with waiting around for her. I focused on my writing, and the method for undertaking it became another obsession. The proof was in the pudding. Publications began to roll in. After landing several well-placed articles, I began to focus on books. By the academic year 2015-2016, I managed to have three books published within a nine-month span. Over the entire period that Sadie was at Gettysburg and I at NYU, I also managed to edit and substantially revise every document that she submitted for her job, including end-of-year review documents, program notes for dance concerts, grant applications, and nearly every installment in her tenure file.

I came to despise Sadie’s priorities and values. Despite being an artist of some renown, she grew more and more obsessed with financial security and other rather pedestrian concerns. And I told her so. But this was not until after she had berated me about money seemingly without cessation. The daughter of a successful doctor, Sadie had never faced financial insecurity, yet she constantly felt financially insecure. The son of a home remodeler and the brother of eight siblings, I had known nothing but financial insecurity, yet rarely worried about money. I had always lived on the edge and was quite accustomed to it. Yet Sadie always felt edgy.

The arguments led to expressions of bitterness about her circumstances. Who was she to criticize me about money? She’d never known financial hardship. Anyway, how was it that she had it made, while I, the worthier academic, struggled without a break? I criticized her for being “nothing but a middle-class householder pretending to be an artist,” and the like.

Thus, I arrive at the final hijacking of our relationship by social justice ideology. Over the course of several years, Sadie had imbibed the pseudo-feminist, identity politics, and victimhood tropes of campus and feminist therapeutic culture. Rather than joining me in my irreverence as she was once wont to do, she now chastised me for being politically incorrect. She didn’t use that phrase, but that’s what her remarks amounted to. There was more of the male-gaze shaming: Why are you looking at my face, she would ask? And my answer was always the same. That’s what people do when they talk to each other.

Above all, Sadie began to resort to the language of “abuse.” But what she called abuse, I call criticism, albeit sometimes intense criticism. She had bought into the notion that language that one did not like represented a form of violence. She wanted to no-platform my critical commentaries, while reporting me to the equivalent of the bias hotlines at her disposal. She wanted a safe space whose walls my contradictory views could not breach.

No doubt I was being demonized by several of her confidantes. Sadie had read websites and visited the Women’s Center on campus, while also seeing a therapist. They all held a particular narrative template based on victimology and seized upon scenarios that might confirm and conform to it. They told her that she was being abused, and she believed them. Once the word abuse had crept between us and mediated every encounter, past and present, all hope for the relationship was gone. This is because the word tainted me, her, and the relationship, irrevocably. She now identified herself as a victim of verbal abuse, and projecting this abuse into the distant past, berated herself for having accepted the purported abuse “for many years.”

In the fall of 2016, I was hospitalized due to a medication crisis. On the phone, I heard Sadie say that she had no intention of visiting me. Crushed but not surprised, I told her I was considering sending an email to the president of her college, telling him what I had done for her career, how I’d revised her every document, including her application letter. She was leaving me now only after she had gotten tenure. I told Sadie I would send it unless she came to the hospital to visit me, just as she had done for her dear friend who had been similarly hospitalized in Baltimore over the summer.

Of course, I had no intention of sending any such email; I just wanted her to visit. While she had once been someone who could understand a maneuver like this as some obvious cri de coeur, her sensibilities had since fallen under the compression of ideological reductionism, and likewise she had lost the ability to recognize it as such. Instead, it represented another example of abuse.

She said she wouldn’t visit someone who had called her a fucking bitch. I hadn’t called her a fucking bitch, but now I said that she was a fucking bitch for such a refusal, even if I had called her a fucking bitch. She ended by saying, “I’ll talk to you later.” And that’s the last thing she ever said to me. Instead of visiting, she blocked me on Facebook, and filed for an order of protection with the local magistrate (which was dismissed for lack of evidence).

This is what’s become of us.

I ask: Have you found the place that makes you want to swallow its rhetoric whole? I have found no such place, but not because I haven’t looked. Rather, I have seen too much to believe that such a place exists.