Science

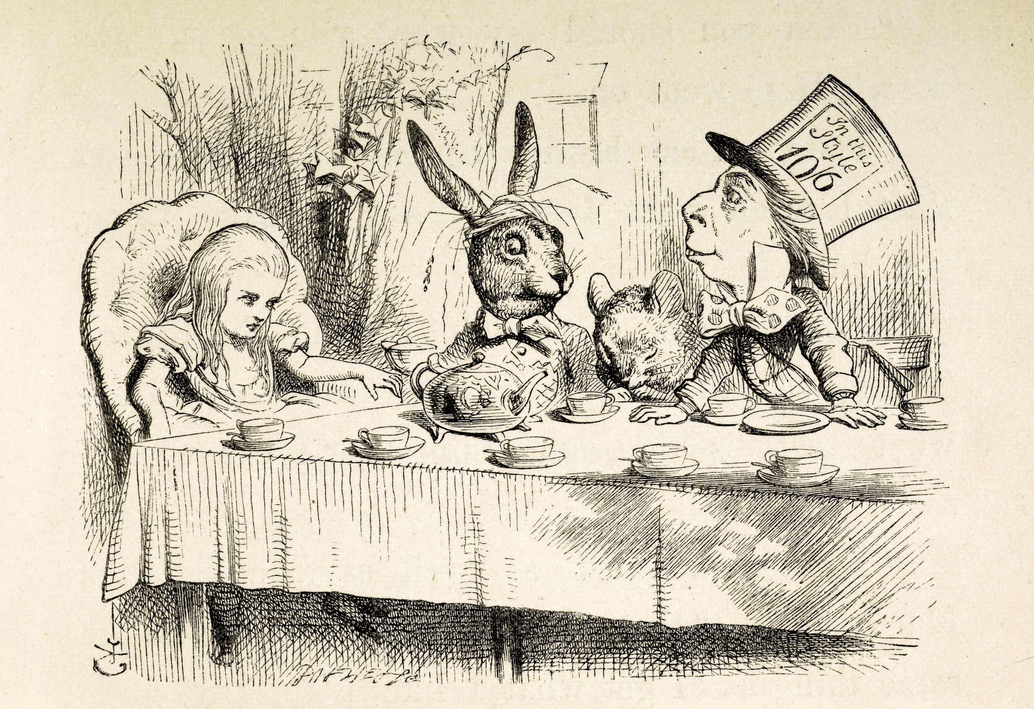

Alice in Blunder Land

“Begin at the beginning,’ the King said, very gravely, ‘and go on till you come to the end: then stop.”

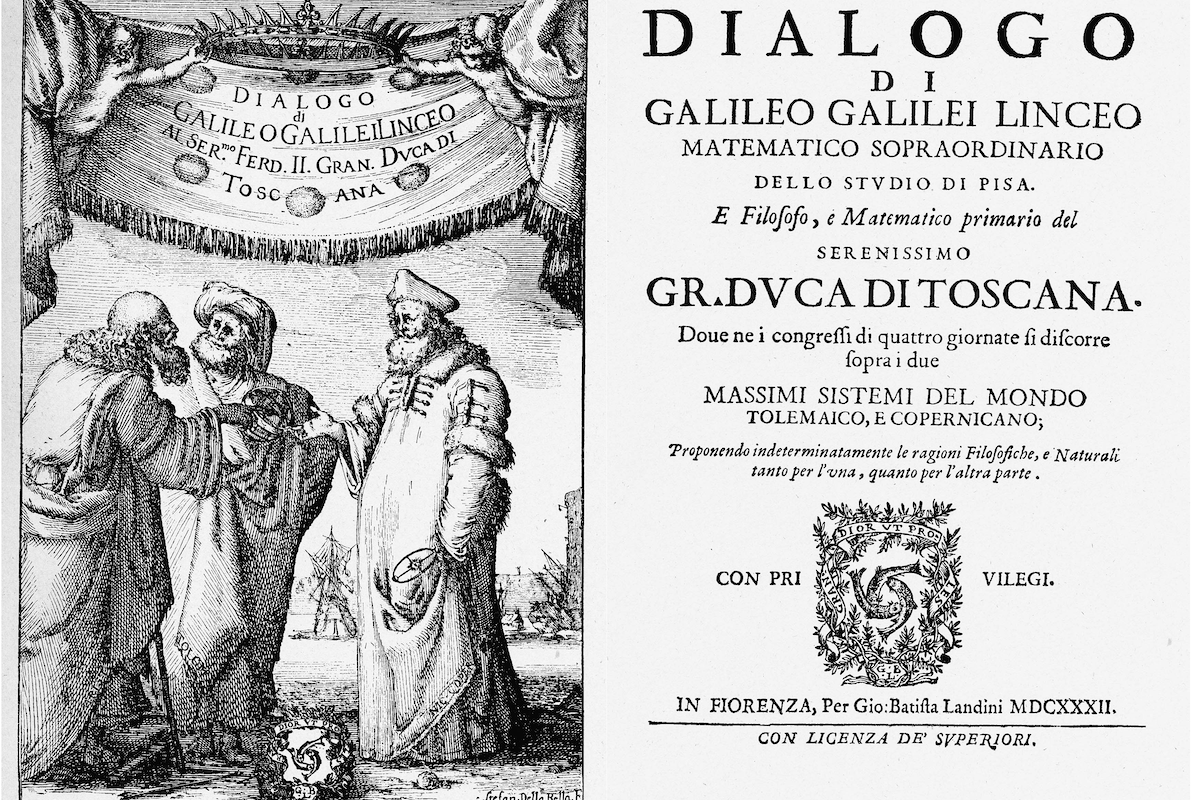

“Begin at the beginning,’ the King said, very gravely, ‘and go on till you come to the end: then stop.”¹ Alice Dreger is a bioethicist employed, until very recently, at Northwestern University. The fact that she felt compelled to resign over a point of ethical principle just underscores the points she makes in the book. She has long been a champion of two things. First: that driving spirit in science – the Galilean one – that sees truth as a spiritual goal and raises a middle finger to those that disagree. Second: The just treatment of those typically marginalized and ignored

because their needs are inconvenient to wider society.²

Galileo’s Middle Finger³ is therefore a series of gripping detective stories exploring the various blunders of scientists who did not see what was coming when they published, of pusillanimous bureaucrats terrified of their University brand being tarnished, of the politically over-zealous, and the personally affronted. Dreger also fearlessly takes on some outright frauds. She is conspicuously thorough and fair-minded throughout a book that, in places, reads like a thriller. It should be required reading on any science course and will serve partly as a survival manual to those who publish in contentious fields.

“If everybody minded their own business, the world would go around a great deal faster than it does.” Alexis de Tocqueville pointed out that in a democracy we get the leaders we deserve. This is because we call it a gaffe when a politician tells the truth. Yet, at the same time, everyone decries our juke-box politicians. Some journalist solemnly presses the button marked “issue A” and the politician, equally solemnly, plays the bland recording of whatever the PR-honed party line is on Issue A. Attempts to press the politician further just produce stony-faced repeats of a message honed and crafted by PR and management-speak gurus to be as inoffensive and open to ambiguity as possible. All the while, of course, the real work goes on in the background away from public scrutiny. This is bad for politics and it is equally bad when this becomes the model for the public understanding of science.

We are in grave danger of producing juke-box scientists to partner our juke-box politicians. This has always been a risk – for reasons I will go into in a minute – but lately the danger has become magnified by the rise of social media and the speed with which ignorance and outrage can spread. This has recreated the gleeful, posturing, sanctimonious hypocrisies of the medieval village mob tying some unfortunate to a ducking stool and laughing at their humiliation and fear.

“If you don’t know where you are going any road can take you there”

If Dreger is right then this process of outrage, and fear of outrage, is going to do the same to scientists as it has to politicians – and we will have deserved everything we get as a result. She documents a series of conflicts between scientists and the outraged in exhaustive detail in a writing style that is by turns witty, erudite, and impassioned. The cliché would be to say that this is a book you can’t put down. And that is true. But not only could I not put it down, at various points I became enraged enough to want to pick it up, hold it high, and hit certain people with it. My emotional reactions to it were so obvious that I made a new friend beside me on my flight to Helsinki who wondered what the hell the book I was reading was all about and could not resist introducing herself to ask me.

A lot of the book reads like a series of breathless detective stories with Dreger uncovering a mix of ignorance, prejudice, and mule-headedness through to malfeasance and out and out fraud. Given that some of these stories have a tension that runs through them that would be spoiled by too much revelation, I will not document them in detail, but instead focus on some of the themes that arise from them.

“Six impossible things before breakfast”

The communication of science to the wider public has always been a tricky issue and this is because science is not common sense.4 Common sense was honed over millions of years to be a bunch of useful tools for understanding things like the ethics of small scale societies, the velocities of human-sized objects and the pragmatic taxonomies of local organisms. Common sense is about the human sized and a truly scientific understanding dramatically alters the scale at both extremes of tiny and vast. Common sense relies on intuition, authority, and tradition and these are all things that are worse than useless for getting at the way the world works underneath the set of evolved adaptations that common-sense thinks of as reality. This is obviously true when one reflects that we have had smart humans for tens of thousands of years but only anything that could be called science for a few hundred of those. Science is recent and most of it is wildly counter-intuitive. This, incidentally, is one reason why scientists speaking with their specialist confidence, but outside of their own discipline, can often make egregious blunders.

“It is better to be feared than loved.”

All of this means that it is almost inevitable that if you are doing science about areas that people care about then you are going to annoy people. It also means that the people who are typically good at science have a set of attitudes to things like authority, intuition, and tradition that are going to annoy people still further. But, it is when science intersects with human nature that offence is most likely to be taken and nothing gets to the heart of human nature faster or deeper than sex. Sex research has even united the house of representatives in the only unanimous decision in its history – to condemn a paper that dared to show evidence that some victims of sexual abuse could make recoveries.5

“Curiouser and curiouser!”

Many of the characters in Galileo’s Middle Finger will be well known to evolutionary scholars and people who go to conferences connected to this field, sex research, or the intersection between medicine and other disciplines. But sex is perhaps the major theme that runs through all of the scandals that Dreger investigates. Whether it’s the forcing of intersex individuals into socially comfortable (but individually painful) categories, the attempted public destruction of the career of renowned sex researcher Mike Bailey over his book The Man Who Would be Queen, or the excoriation of Thornhill and Palmer’s attempt to shed biological light on the phenomenon of rape – sex is the thread joining all of these. Even the attempted vilification of Napoleon Chagnon on utterly grotesque trumped-up charges of genocide of the Yanomamo had a sexual theme. It was his finding that reproductive success (rather than property) drove violence in a horticultural society that so incensed some members of the AAA that some were willing to allow him to be attacked on the flimsiest of evidence. While there were prominent anthropologists like Margaret Mead who resisted calls for a de facto book burning of Chagnon’s work, far too many in anthropology and related disciplines were willing to stand by and see Chagnon’s reputation sullied. Fortunately all the charges against him were thoroughly debunked6 but at what cost to Chagnon personally and to the reputation of the field?

“Off with their heads!”

In all cases Dreger documents the attacks are viciously personal. In all cases an ideology and/or a sense of personal identity were threatened. Anyone used to social media sees issues of so-called identity politics daily. However, if all public debate, let alone scientific exchange, is not to be reduced to trivial exchanges of “well he would say that, wouldn’t he” then all of us have to resist the temptation to play the ball and not the man.

“I can’t go back to yesterday because I was a different person then.”

Dreger understands all about the medical concept of risk factors and provides some helpful examples of these for those who might get political backlash for their work. She warns that any study of human behaviour is risky with special notice being applied to areas of sex, gender, or race. If your work does not allow you be fitted into a simple political camp then you are likely to get attacked by both of them. If you did not take the precaution of being from some sort of oppressed minority then this is a further danger. Being a good writer is risky – because then your books will actually be read by those who might become offended. Most interestingly she identifies the Galilean personality as the biggest risk factor of all. This is the personality that behaves as if the truth matters more than anything else. More than feelings, more than politics, more than the self. The Galilean personality is the one that animates science, because nothing other than this can brush aside the things that hinder science: reliance on authority, tradition and intuition.

But there is hope offered. Of sorts. Well, Dreger offers some tips on how to weather the storms that might result. Some of these are obvious – not to give gratuitous offence, take as much PR training as your university offers and get to know the people offering it. Get them to train you to write your own press releases. Given that for many journalists there are only four characters in a story –the hero, the villain, the victim and the freak – this is clearly useful advice. She says that lawyers and groups like FIRE are worth getting to know.

“Imagination is the only weapon in the war against reality.”

One of the themes that runs throughout the book is that assumptions are the things we do not know we are making. Jon Haidt7 has repeatedly drawn attention to the way that social and behavioural sciences assume that their dominant political viewpoint (typically left wing and liberal) represents reality rather than the lens through which we view the world. Never could this be clearer than in Galileo’s Middle Finger. For example, far too often the useful corrective of exploring one’s own biases has become weaponized into debate-closing triumphant cries of “check your privilege” by those who want to flaunt their humility rather than engage with the facts. Dreger is one of very few who is actually capable of plucking the beam from her own eye so that she can more clearly see the mote in her neighbour’s. Her commitment to truth is such that she’s willing to genuinely explore her own preconceptions and political biases.

That’s very rare in any of us and deserves due credit. But her book does highlight one area of concern for specifically evolutionary scholars. Dreger openly admits that, as a feminist, she was taught to hold evolutionary psychology in contempt (p. 108). Dreger is a fair minded scholar and follows the evidence and argument where it leads. She’s unafraid to explore her own biases and mistakes and to change her mind. But how many of us are like her? More importantly – we all need to openly acknowledge that it is a species’ typical behaviour to make up our minds for political and/or moral reasons and then seek out the evidence to support this. Our field is therefore never going to be free of the need to win hearts as well as minds. We also need to recognise that standing up for academic freedom is easy when it is for people we like and whose ideas we agree with. But its importance is not about taking a side in a scientific controversy.

Science is itself the side.

This review was originally pubished in Evolution, Mind and Behaviour 13(2015), 47–51 DOI: 10.1556/2050.2015.0004

References

- Carroll, L. (2000). Alice’s adventures in wonderland. Broadview Press.

- Dreger, A. D. (1998). Hermaphrodites and the medical invention of sex. Harvard University Press.

- Dreger, A. (2015). Galileo’s middle finger: Heretics, activists, and the search for justice in science. Penguin.

- Wolpert, L. (1994). The unnatural nature of science. Harvard University Press.

- Zucker, K. J. (2002). From the editor’s desk: Receiving the torch in the era of sexology’s renaissance. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 31(1), 1–6.

- Hagen, E. H., Price, M. E., & Tooby, J. (2001). The major allegations against Napolean Chagnonand James Neel presented in Darkness in El Dorado by Patrick Tierney appear to be deliberately fraudulent. University of California, Department of Anthropology, Santa Barbara.

- Haidt, J. (2012). The righteous mind: Why good people are divided by politics and religion. Vintage.